The loss of physical and functional capacities in older adults, as well as cognitive decline, has been a growing concern, especially in countries with a more substantial ageing population where the demand for long-term residential care has increased (Buckinx et al, 2015; Prince et al, 2015; Reilly et al, 2015; United Nations, 2016). Physical and functional decline pose a particular challenge in nursing homes, where residents often experience a deterioration in health and growing dependence in activities of daily living (Grönstedt et al, 2013). To preserve and improve residual abilities among nursing home residents, interventions with proven efficacy are needed (Tolson et al, 2011).

Mobility and functional status appear to be positively influenced by physical exercise: some studies have shown how physical exercise interventions could prevent or slow functional decline in older people living in nursing homes (Slaughter et al, 2015; Laffon de Mazières et al, 2017), although not all evidence is unanimous, and more studies about the intensity and duration of such interventions are needed (Forbes et al, 2015).

The aim of the present study was to describe the effect of a tailored intervention involving physical exercise on both mobility and functional decline in nursing home residents during a 1-year follow-up period.

Methods

An observational cohort study was conducted in a nursing home in the province of Padua, Italy. All residents who were admitted to the nursing home between January 2014 and December 2016 were enrolled in the study. The follow-up period was set at 1 year. Participants who dropped out of the study before the end of the follow-up time-due to either death or discharge from the nursing home-were not included in the subsequent analyses.

Data collection and outcome measures

Information on gender, age, level of education, main profession in working life, functionality, mobility, degree of dementia and adherence to tailored physical exercise interventions was collected. Data were collected at the baseline (t0) and at 6 (t1) and 12 months (t2) after the intervention.

Professions were categorised as follows: (i) unqualified professions, (ii) qualified professions, (iii) technical professions, (iv) high leadership/intellectual professions/armed forces, according to the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) classification (ISTAT, 2021). The degree of dependence in functionality and mobility was assessed using the Barthel index, which examines the abilities of a person to perform daily activities (nutrition, personal hygiene, bath/shower, clothing, toilet use, urinary continence, intestinal continence, wheelchair/chair-bed transfers, walking/wheelchair use and stairs) (Jacelon, 1986). The degree of dependence in the sphere of functionality was separately assessed (including the first seven domains; hereafter referred to as ‘functionality dependence score’ (FunDepScore)) and mobility (including the latter three domains; hereafter referred to as ‘mobility dependence score’ (MobDepScore)). The FunDepScore ranges from 0 to 60 while the MobDepScore ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater dependence (0=independent patient; 100=fully dependent patient), according to the tool used at the regional level (Regione del Veneto, 2021).

The degree of dementia was assessed using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, which allows assessment for very mild borderline and very severe forms of dementia (Hughes et al, 1982). The following categories were considered in the analyses: absence of dementia (CDR=0 and 0.5), mild/moderate dementia (CDR=1, 2), severe/very severe/terminal dementia (CDR=3, 4, 5).

For each resident, a fully tailored exercise plan was prepared and carried out by qualified nursing home staff (physicians specialising in physical medicine and rehabilitation, physiotherapists and personal trainers). Exercise sessions were carried out three times a week, each lasting approximately 45 minutes. Each session could include a combination of passive, assisted or active mobilisation exercises, depending on the resident's need and residual capacity. The proposed exercises were specifically aimed at improving muscle strength, postural transitions, balance, walking ability and spatial orientation. Sessions would also include training in the use of mobility aids and dancing. Adherence to the exercise plan was classified as ‘no adherence’, ‘partial adherence’ (if the plan was adhered to only between t0 and t1 or t1 and t2), and ‘complete adherence’ (if the plan has been adhered to for the entire follow-up period). Adherence to the exercise plan was defined as an attendance rate of ≥80% in each time frame.

Two indicators describing functional and mobility decline were considered as dependent variables:

- Functional decline was defined as an increase in FunDepScore between t0 and t2

- Mobility decline was defined as an increase in MobDepScore between t0 and t2.

Data analysis

Bivariate analyses were used to examine the association between adherence to the physical exercise plan and the functional and mobility decline indicators. A chi-square test was used to analyse categorical data and to examine differences between groups showing decline and stability improvement.

A multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine the independent association of the tailored physical exercise interventions with mobility decline. This outcome was entered as a dependent variable, and the following independent variables were considered as potential confounders: gender, age (as a continuous variable), level of education (0–4 years, 5–7 years, 8–12 years, 13 years or more), main profession in working life and CDR classes. Adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. All p-values reported are two-sided, and a p-value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1. Routinely recorded clinical data were processed in an anonymous and aggregate form, with informed consent provided by patients. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Italian Law Decree n. 196/2003 and the EU General Data Protection Regulation.

Results

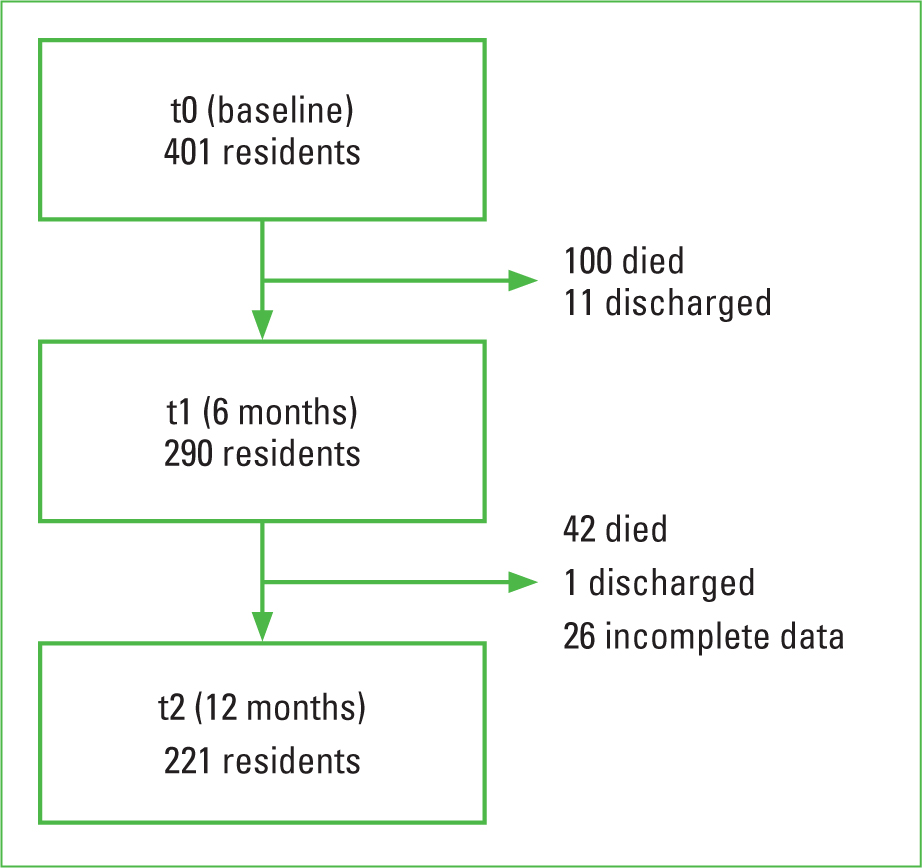

Of 401 participants, 221 remained at the end of the follow-up period (Figure 1). No significant difference was found regarding the distribution of all investigated variables between the groups of participants who completed follow-up and those who did not, with the exception of gender: the proportion of women was 76.9% in the study group versus 61.7% in the dropout group (p=0.001).

Figure 1. Participants included in the study

Figure 1. Participants included in the study

The mean age of the participants was 84.1 years (SD=8; range, 58–104 years), and 170 (76.9%) were women; 131 (59.3%) residents were found to have mild or moderate dementia, and 67 (30.3%) had severe, very severe or terminal dementia (Table 1). The most frequent type of dementia was vascular dementia (35.4%), followed by Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia (both 16.2%); Lewy body disease and alcohol-related dementia accounted for 3.0% and 0.5%, respectively; 9.6% of patients had a diagnosis of mixed dementia, while the type of dementia was not recorded in 19.2% of participants. Considering the adherence to the physical exercise plan, 104 (47.0%) residents never performed the exercises, 66 (29.9%) residents performed them for 6 months, and 51 (23.1%) residents performed them for 12 months.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population

| Total (n=221) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (23.1) |

| Female | 170 (76.9) |

| Age | |

| <80 years | 53 (24.0) |

| 80–84 years | 48 (21.7) |

| 85–89 years | 62 (28.1) |

| ≥90 years | 58 (26.2) |

| Level of education | |

| 0–4 years | 29 (13.1) |

| 5–7 years | 126 (57.0) |

| 8–12 years | 44 (19.9) |

| 13 years or more | 19 (8.6) |

| Job in working life | |

| Unqualified professions | 122 (55.2) |

| Qualified professions | 34 (15.4) |

| Technical professions | 42 (19.0) |

| High leadership/intellectual professions/armed forces | 23 (10.4) |

| CDR classes | |

| No dementia | 23 (10.4) |

| Mild or moderate dementia | 131 (59.3) |

| Severe, very severe or terminal dementia | 67 (30.3) |

| Adherence to exercise plan intervention | |

| No adherence | 104 (47.1) |

| Partial adherence | 66 (29.9) |

| Complete adherence | 51 (23.1) |

As shown in Table 2, although the association between adherence to the physical exercise plan and functional decline was not statistically significant, mobility decline was greater among participants who never took part in any physical activity intervention (86.5%) or did it partially (81.8%) during the follow-up period compared with those who did so for the whole period (60.8%; p<0.001).

Table 2. Adherence to the physical exercise plan intervention by functional and mobility decline

| Total (n=221) | Functional decline | Mobility decline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p | n (%) | p | |

| No adherence | 93 (89.4) | 0.360 | 90 (86.5) | 0.001 |

| Partial adherence | 55 (83.3) | 54 (81.8) | ||

| Complete adherence | 42 (82.4) | 31 (60.8) | ||

| Total | 190 (86.0) | 175 (79.2) | ||

Table 3 shows the results from the multivariate logistic regression, which estimated the effect of physical activity on decline in mobility. Residents who never participated in physical activities had a higher risk of mobility decline compared with those who participated in physical activities for 12 months (AOR=4.93; p<0.001). A lower but significant effect was also seen in residents who participated in physical activities for only 6 months (AOR=3.23, p=0.01). Additionally, dementia was a significant predictor for mobility decline: residents with dementia, whether mild or severe, showed a higher risk of decline compared with residents without dementia (AOR=3.25, p=0.04 and AOR=5.16, p=0.01, respectively).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression model of individual variables associated with mobility decline

| AOR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence to exercise plan intervention (ref: complete adherence) | |||

| Partial adherence | 3.23 | 1.29–8.08 | 0.01 |

| No adherence | 4.93 | 2.00–12.17 | 0.001 |

| Gender (ref: female) | |||

| Male | 1.75 | 0.69–4.47 | 0.24 |

| Age (years) | 0.98 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.32 |

| Level of education (ref: 13 years or more) | |||

| 8–12 y | 1.74 | 0.39–8.09 | 0.46 |

| 5–7 y | 3.14 | 0.68–14.49 | 0.14 |

| 0–4 y | 1.16 | 0.22–6.09 | 0.86 |

| Professions (ref: unqualified professions) | |||

| Qualified professions | 1.24 | 0.42–3.70 | 0.70 |

| Technical professions | 2.08 | 0.65–6.63 | 0.22 |

| High leadership/intellectual professions/armed forces | 3.22 | 0.65–15.61 | 0.15 |

| CDR classes (ref: no dementia) | |||

| Mild or moderate dementia | 3.25 | 1.04–10.16 | 0.04 |

| Severe, very severe or terminal dementia | 5.16 | 1.50–20.15 | 0.01 |

AOR=adjusted odds ratio; CI=confidence interval

On the basis of the findings of the logistic regression, further analysis was conducted to evaluate the variation in the mean MobDepScore by participation in physical activities and CDR classes (Table 4). While a significant increase in MobDepScore was noted in patients with both mild (from 29.7 to 32.2, p=0.05) and severe dementia (from 32.7 to 36.3, p<0.001) who did not take part in any physical activity for the whole follow-up period, substantial stabilisation was noted in patients with mild dementia who performed physical activity for 12 months (p=0.65) and those with severe dementia who engaged in the organised physical activities for both 6 and 12 months (p=0.49 and p=0.66, respectively). Among residents without dementia, a significant improvement in mobility was seen in those not taking part in physical activities organised by nursing home staff (from 12.8 to 9.6, p=0.02), while the MobDepScore showed no significant variation between those who attended physical activity interventions for 6 or 12 months (p=0.12 and p=0.95, respectively).

Table 4. Mobility dependence score (MobDepScore) trend according to physical activities and CDR classes

| Adherence to exercise plan intervention | n | MobDepScore* t0 | MobDepScore* t1 | MobDepScore* t2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| No dementia | NoPartialComplete | 977 | 12.8 (11.7)24.3 (11.9)25.7 (14.4) | 12.6 (11.5)22.9 (10.7)21.3 (14.1) | 9.6 (11.6)20.4 (12.2)20.9 (13.5) | 0.020.120.95 |

| Mild or moderate dementia | NoPartialComplete | 494438 | 29.7 (11.1)29.2 (10.6)23.8 (12.6) | 31.6 (11.1)29.9 (10.6)22.6 (11.6) | 32.2 (11.5)32.5 (9.7)23.8 (12.8) | 0.050.010.65 |

| Severe, very severe or terminal dementia | NoPartialComplete | 46156 | 32.7 (10.7)28.4 (14.2)18.2 (10.5) | 34.2 (9.3)31.1 (12.4)20.2 (9.6) | 36.3 (7.3)31.2 (10.5)19.2 (11.3) | <0.0010.490.66 |

0=fully independent patient;

40=completely dependent patient.

t0=baseline; t1=6 months; t2=12 months

Discussion

This study shows how tailored physical exercise interventions can have a positive effect on delaying mobility decline among nursing home residents, although a significant effect of physical activity on functional decline was not demonstrated. The risk of a decline in mobility was almost five times higher in those not adhering to tailored physical exercise interventions compared with those who did for the whole follow-up period. In particular, residual mobility capacity was seen to be preserved in those with dementia.

Benefits from partial adherence to the exercise plan were limited but were still associated with a three-fold increase in mobility decline compared with complete adherence to the physical activity plan. The importance of continuous physical activity was highlighted by Frändin and colleagues, who reported that after a 3-month intervention followed by a 3-month period without intervention, mobility and functional abilities in the intervention group did not differ from the control group (Frändin et al, 2016). Although, in the present study, the reasons behind the suspension of physical activities could not be determined, the results further support these findings and the need for a well-planned intervention to be carried out regularly over time.

On the one hand, higher severity of dementia was found to be associated with a higher risk of mobility decline; on the other hand, patients with dementia were found to be those who could benefit more from physical activity interventions in terms of delaying mobility decline. The association between mobility and cognitive status has been described previously: older people with cognitive impairment tend to have poorer physical performances and report higher levels of disability, and the rate of progression to disability seems to be affected by impaired cognitive function (Tolea et al, 2016).

In the present study, during the 1-year follow-up, patients with dementia (either mild or severe) who adhered to the physical activity plan showed, on average, a substantial stabilisation of mobility capacity, in contrast with those who did not adhere to the plan, who showed a significant worsening in mobility capacity. To the best of the authors' knowledge, there are no studies analysing the influence of physical exercise in a heterogenic institutionalised population. A systematic review on the effects of physical exercise on the health of people living with dementia in nursing homes underlined how mobility improves significantly after a physical exercise intervention (Brett et al, 2016), but it did not investigate how cognitive impairment modifies the effect of such an intervention.

Among nursing home residents without dementia, a significant reduction in the MobDepScore over time in those who did not adhere to the exercise plan intervention, otherwise interpretable as an improvement in motor skills, seems paradoxical. This finding may be due to the fact that patients in this group have residual capacity to perform physical activity on their own, and, therefore, refuse the exercise plan. They are more independent, can train on their own and have fewer physical inabilities. Moreover, people with dementia of greater severity who are not bed-ridden rarely have actual physical inabilities and, when stimulated, can maintain and improve their physical status.

Limitations

The study has some limitations. First, although the follow-up period was longer than that in many other studies, a 1-year follow-up may not be adequate to outline the long-term trend in mobility and function capacity in people living in nursing homes. However, regarding this specific setting, people do not stay in nursing homes for long periods, since they often need to be hospitalised or die after few years or even months after the admission, as witnessed by the high dropout rate in the present study. Second, data on the onset of new conditions that may have acted as the cause for refusal to engage in the physical activity plan prescribed were not recorded, nor were reasons for non-adherence. Last, the use of the Barthel index has been pointed out as controversial in patients with severe dementia (Yi et al, 2020), and these individuals accounted for around 30% of the sample in the present study.

Conclusions

Adherence to a tailored physical exercise plan among nursing home residents showed clear benefits in terms of delaying mobility decline. Further, non-adherence to the plan is associated with up to five times higher chance of developing mobility decline. The best results were achieved when physical activity interventions were carried out regularly over time, although partial adhesion to the proposed plan still had a residual benefit.

The findings of this study could have crucial implications on daily practice in nursing homes, suggesting that preventing or slowing physical decline in nursing home residents is an achievable goal and that all patients would benefit from the offer of a tailored physical activity plan, including those with higher level of cognitive impairment.

KEY POINTS

- Physical and functional decline in older adults poses a particular challenge in nursing homes, where residents often experience a deterioration in health and the growing dependence in activities of daily living has been a growing concern

- A combination of passive, assisted or active mobilisation tailored on resident's need and residual capacity may reduce up to five times the chance of developing mobility decline, especially if carried out regularly over time

- A stabilising effect on mobility decline was seen also in patients with dementia of greater severity

CPD REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How can physical and functional decline be avoided or at least delayed in nursing home residents engaging in physical exercise?

- Which kind of exercises might be included in the individually tailored plan interventions?

- On the basis of this article, how would you go about engaging your patients in physical exercise sessions?