Loneliness is a profound and widespread human experience that transcends age, culture and socioeconomic status. However, its impact is particularly significant among older adults, who may face unique challenges that contribute to feelings of isolation and disconnection (Reis da Silva, 2023a; 2024a).

Although the term loneliness is often used interchangeably with other related terms, it has a distinct and specific meaning. Aloneness is one such concept; it refers to an undesirable and involuntary state in which a person perceives and experiences being alone (Tzouvara et al, 2015). Being alone is a more deliberate and manageable situation, when a person decides to be by themselves rather than socialise. While there is no clear connection between the two ideas, it is commonly accepted that being alone increases a person's likelihood of feeling lonely (Tzouvara et al, 2015). Another idea that is sometimes confused with loneliness is social isolation. Since it reflects a person's diminished social network, it may be seen as an intermediate concept between loneliness and aloneness. Depending on how one perceives their own social relationship patterns, an individual may choose to be lonely or socially isolated. People choose to draw a line between loneliness and social isolation when they experience unwanted social isolation, which can happen for a variety of reasons (Reis da Silva, 2025a). In contrast to loneliness, solitude evokes a more favourable feeling. It implies that complete independence and a peaceful experience may be had in isolation and is unrelated to the negative emotional assessment of a situation. Consequently, loneliness is associated with a negative emotional assessment of one's status, whereas solitude is associated with a good assessment (Tzouvara et al, 2015).

Conceptualisation of loneliness

Loneliness is a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses emotional, cognitive and social dimensions (Reis da Silva, 2024). At its core, loneliness reflects a perceived discrepancy between an individual's desired and actual social relationships. It is important to recognise that loneliness is subjective, meaning that it is not solely determined by the quantity of social interactions but rather by the quality and meaningfulness of those connections (Rosedale, 2007; Reis da Silva, 2024). From a psychological perspective, loneliness can be conceptualised as a distressing emotional response to perceived social isolation. It involves feelings of emptiness, sadness and longing for companionship. Social cognitive theories suggest that loneliness may stem from negative self-perceptions and beliefs about one's social worth or ability to form meaningful relationships (Reis da Silva, 2024).

Over time, the vocabulary and conventional knowledge around being alone have evolved (Schaler Buchholz, 2000). The Oxford Universal Dictionary (1964) states that the word ‘alone’ originally denoted wholeness in one's own existence (All+one=alone).

As a result, the risks and negative effects of being alone (and, consequently, of loneliness) were not as well understood as they are today (Rosedale, 2007). D'Aboy (1972) summarised the definitions of the term loneliness in dictionaries and found that while most individuals can relate to the sensation, there is no universally accepted description for it. Dictionary definitions of loneliness include physical alienation, mental alienation, isolation, separation, aloneness, estrangement and solitude. These definitions represent both good and bad meanings as well as circumstances that are deliberate and involuntary. According to D'Aboy (1972), the ideal way to conceptualise loneliness is as a continuum that ranges from completely negative states or circumstances to ones that are unclear to those linked to good feelings.

The Oxford English Dictionary (2023) explains that the term ‘alone’ was first recorded in usage during the Middle English era (1150–1500). The Oxford English Dictionary (2023) traces the first known use of ‘alone’ to the Ormulum, around 1175. This concept evolved to mean being alone, by oneself, without others present, and unaccompanied. Over time, it was also applied to objects, animals, and other entities (from 1175). Its use was reinforced by possessive adjectives or personal pronouns, often prefixed, as seen in phrases like ‘by oneself.’ Additionally, it appeared in attributive, colloquial and obsolete (later Scottish) usage (1300–1827). By 1921, it was used to describe individuals, locations and timeframes as alone, isolated or lonely.

The link with sacred loneliness

Thomas Wolfe's quote from God's Lonely Man (1930) highlights the existential view of loneliness, which exists on a spectrum rather than being dichotomous. Loneliness is described as ‘inability to realise the meaning in one's own life,’ ‘feelings of disconnectedness’ and ‘a subjective yet negative feeling of lacking social relationships’ (Hartley, 1961; Heinrich and Gullone, 2006; Bekhet et al, 2008; Préher, 2011; Rokach, 2013; Banerjee, 2021). Loneliness has been associated with heart disease, stroke, diabetes, depression, anxiety, suicide and dementia, though the causality is unclear (Cacioppo et al, 2002; Routasalo and Pitkala, 2003; Rosedale, 2007; Ong et al, 2016; Banerjee, 2021; Reis da Silva, 2024).

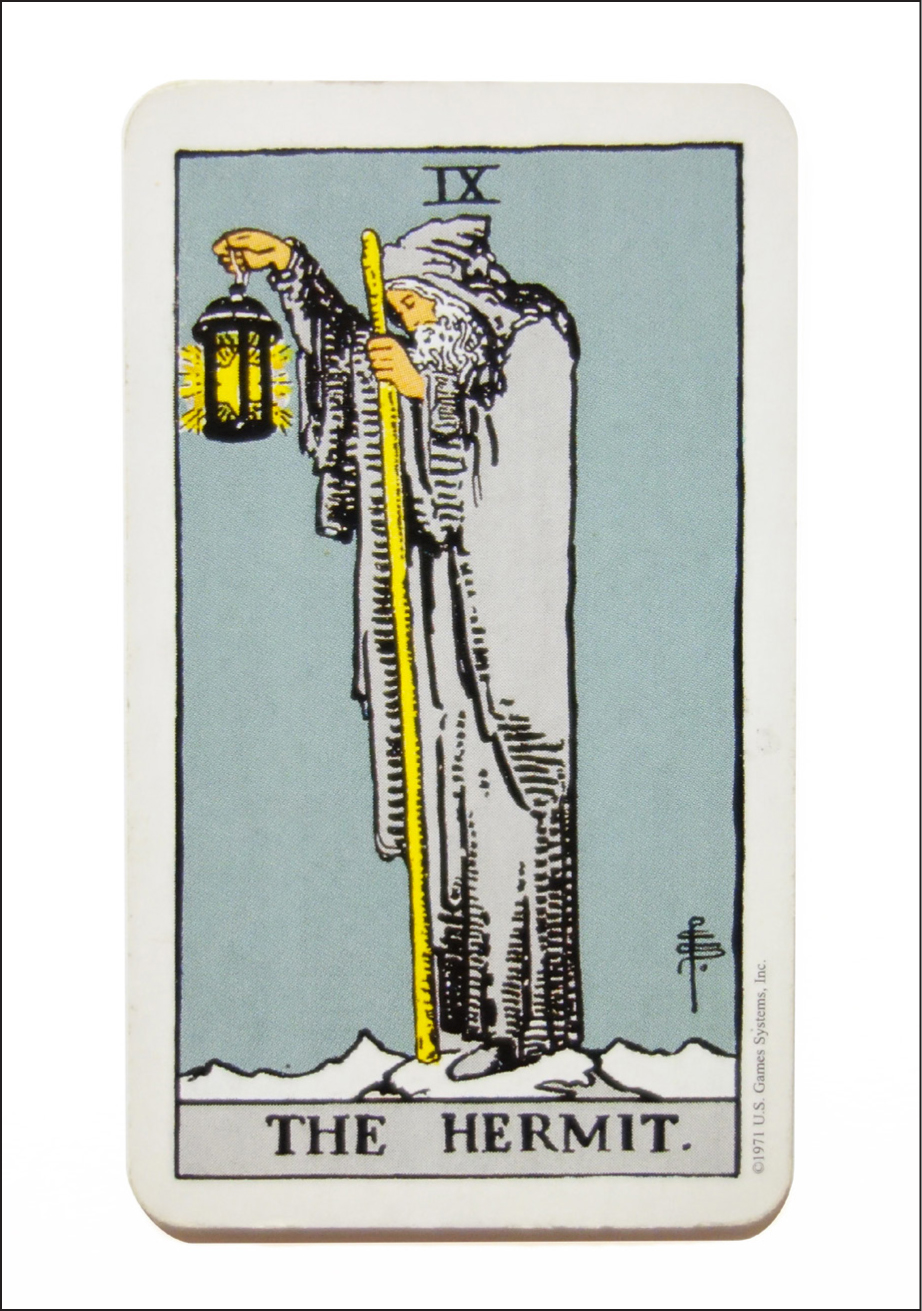

The concept of an elderly man living alone has a long-standing meaning, as seen in various cultural and symbolic representations. For instance, this is reflected in the Tarot, specifically in the Waite-Smith-Rider deck. The Hermit, the ninth card of the Major Arcana, depicts an elderly man with white hair and a long white beard (Figure 1). Standing alone at the summit of a snow-covered mountain range, he holds a lamp at eye level, which bears the Seal of Solomon—a symbol of wisdom. According to Mizrahi (2020), the number nine represents the highest power attainable by a single digit, its mathematical ability to return to itself, and the number of days required for initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The Hermit's lamp and light symbolise wisdom, inner light of truth and conscience, and the symbol of power and authority. His long overcoat signifies protection. The Hermit embodies opposite poles of being, with his lamp and beard suggesting the fiery yang and his flowing robe indicating the dark watery yin (Mizrahi, 2020).

The figure of time associated with the Hermit derives from the image of the classical god Saturn, who was the god of time and depicted as a hunched old man. While in the early Renaissance, the perception of Saturn and time were a negative destructive force, towards the end of the 15th century, Saturn came to be seen positively as a god of contemplation and artistic genius (Mizrahi, 2020). In terms of iconology, Waite and Smith chose to depict the Hermit in such a manner intentionally, suggesting that divine mysteries secure their own protection from those who are unprepared.

In India, older people are often looked up to as ‘wise, experienced and mature,’ and the concept of Vaanaprastha can be applied for a healthy ageing approach where one can slowly prepare themselves for old age rather than lamenting about the ‘loss’ associated with it. Reconciliation with ageing has been shown to be one of the components of healthy longevity, improving self-esteem and fostering resilience (Banerjee, 2021; Reis da Silva, 2025b). Ultimately, it is the personal choice of each individual as to what path they wish to take, and none is absolute.

According to religious teachings, loneliness is the result of separation and isolation, which is an unpleasant and often painful state. It is preventable, or at the very least, actionable. Additionally, even while surrounded by people, one can feel lonely.

Philosophical views of loneliness

Philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Sartre, Buber, Mijuskovic and Mutakas have all acknowledged the significance of loneliness in human life, and the topic has been the focus of philosophical discussion since antiquity (Rosedale, 2007). Plato (428–347 BC), as reported by Adler and Van Doren (1977), thought that loneliness was a drive to escape solitude, which affected conduct and consciousness. According to Aristotle (384–322 BC), no one would prefer to live in solitude and a lone individual would either become God or a beast (Irwin, 1985).

Kierkegaard (1843–1885) argues that loneliness may be a route for self-discovery since it enables one to face their dread of nonbeing, which opens the door to liberation and a more profound understanding of reality. According to some existentialists (Sartre, 1957; Heidegger, 1962; Tillich, 1963), loneliness is a necessary aspect of being human since it enables people to reflect, ask themselves why they are doing things, look for freedom, uncover the truth, and find bravery and purpose in the midst of despair. Schaler Buchholz (2000) explains that Sartre's (1957) frequently misunderstood dictum that ‘hell is other people’ meant that admitting the existence of other people results in painful realisations of one's own loneliness as well as the realisation that there is no basic nature to man. It is inside this agonising apartness that the human is allowed to form and build a distinct self.

According to Buber (1958), loneliness is an abnormal aspect of being human and according to Mijuskovic (1977), individuals only become conscious of their loneliness when they realise that they are alone. Moustakas (1972) explains that loneliness is a critical period of life when fundamental elements are tested and is frequently invoked in the wake of tragedy, sickness, or death.

Psychological views of loneliness

The idea of loneliness is intricate and multifaceted, including several facets of human existence (Figure 2) (Tzouvara et al, 2015; Reis da Silva, 2024). It is described as the unmet demand for interpersonal interactions with other people, which results in an unsatisfied life. According to Sullivan (1953), loneliness is the result of unmet demands for closeness and attachment. This definition highlights the significance of social and emotional needs in the experience of loneliness.

According to Weiss (1973), loneliness is not just a result of being alone; it may also result from unmet social demands for a connection or group of relationships. Inspired by Weiss's (1973) methodology, Killeen (1998) characterises loneliness as a dehumanising state that arises from the emptiness that individuals experience as a result of their unsatisfied social and emotional lives. Leiderman's (1980) perspective is that loneliness is the feeling of knowing that you are away from people but nevertheless needing them all the time. Peplau and Perlman (1982) describe loneliness is an unpleasant feeling brought on by both quantitative and qualitative flaws in one's social ties.

Rokach (1990) believes loneliness is a universal phenomenon that affects humans at all stages of life, including conception and death. Younger (1995) explains that loneliness is the bored, alone and aimless condition that results from being alone when one needs to be near to, and connected to, people.

According to de Jong Glerveld (1998), loneliness is a condition that arises from a perceived mismatch between one's expectations and experiences in social connections. Anderson (1998) defines loneliness as a phenomena that arises when people feel dissatisfied with the quantity of interpersonal, social or communal ties they have. This highlights the significance of having a large number of social relationships.

Rook (1984) describes loneliness is an uncomfortable state that results in emotional pain. She emphasises the dearth of possibilities for emotional connection and social integration. The complexity and multifaceted character of loneliness is reflected in these conceptualisations, with several academics highlighting the significance of social and emotional needs. Notwithstanding these nuanced differences, the general opinion is that loneliness is a widespread, detrimental, subjective and crippling idea.

Robert Weiss's (1973) interactionist theoretical approach holds that the lack of an intimate figure and an insufficient social network are the main causes of loneliness (Singh and Kiran, 2013; Tzouvara et al, 2015). He distinguishes between two forms of loneliness: social and emotional (Weiss, 1973). Social loneliness stems from the apparent absence of social relationships, whereas emotional loneliness is brought on by the death of a loved one, divorce or being alone.

Each type of loneliness has its own set of symptoms: social loneliness results in agitation, restlessness and boredom; emotional loneliness causes anxiety, despair, misery and aggression (Weiss, 1973). However, Weiss' (1973) interactionist approach has come under fire for blaming loneliness's origins entirely on unfavourable circumstances.

Research on loneliness indicates that other variables, which are not always negative, such as gender (Golden et al, 2009; Thomopoulou et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2011), age (Holmèn et al, 1992; Victor et al, 2002; Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2007), and culture (Chalise et al, 2010; Lou and Ng, 2012; Fokkema et al, 2013) also play a role in the development of loneliness.

Psychodynamic theorists emphasise that deficiencies in early and childhood bonds have a major role in the development of loneliness in later life (Tzouvara et al, 2015). They see loneliness as a mental condition indicative of neurosis (Singh and Kiran, 2013). However, this theory ignores other significant factors that contribute to loneliness, such as age, culture and going through a loss (Donaldson and Watson, 1996; Tzouvara, 2015). It is based only on clinical observations of individuals with mental illness (Perlman and Peplau, 1982).

Leading the existential theory, Tillich (1963) and Moustakas (1972) contend that loneliness results from separateness, an existential condition of human existence and that all individuals are ‘ultimately alone’ (Perlman and Peplau, 1982). Existentialists distinguish between ‘true loneliness’ and ‘anxiety loneliness,’ where ‘true loneliness’ refers to the awareness that one is alone in life, while ‘anxiety loneliness’ is a coping strategy used to prevent oneself from realising one is alone (Tzouvara et al, 2015).

One of the main drawbacks of existential theory is that it does not distinguish between the subjective and objective meaning of feeling (Donaldson and Watson, 1996). Loneliness is undoubtedly ‘an existential condition’ that is ingrained in one's experiences, according to an existential viewpoint. Therefore, existential theorists appear to view people as lonely without taking into account their preference.

While those who feel lonely are not always alone, those who prefer to be alone do not always feel lonely (Tzouvara et al, 2015). The cognitive method places a strong emphasis on how crucial cognitive functions are for controlling and reducing feelings of loneliness (Tzouvara et al, 2015). Prominent proponents of the cognitive method, such as Peplau and Perlman (1982), contend that loneliness may arise from a sense of having less social ties than one would like.

Additionally, they contend that this approach's mediating effects are among its most notable features. In other words, between the perceived level of loneliness (resulting from social deficits) and the actual degree of loneliness, cognitive processes play a mediating role (Tzouvara et al, 2015). For instance, cognitive functions such as social skills and self-esteem can be used to control, mitigate or even eliminate feelings of loneliness.

The cognitive method, which is based on the attribution theory, highlights behavioural and personality factors in addition to situational and environmental attributions. It appears that the cognitive approach overlooks the possibility of cultural influences on loneliness (Tzouvara et al, 2015).

Impact of loneliness in older people

Loneliness can have profound implications for the health and wellbeing of older adults. As individuals age, they may experience a range of life transitions and losses, such as retirement, bereavement and physical health limitations, which can increase their vulnerability to loneliness (Reis da Silva, 2024b; 2025c). One of the most significant impacts of loneliness in older adults is its association with poor mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety and cognitive decline (Reis da Silva, 2025d). Chronic loneliness has been linked to changes in brain structure and function, contributing to accelerated cognitive decline and increased risk of dementia (Reis da Silva, 2025d).

Loneliness also takes a toll on physical health, with studies linking it to higher rates of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and mortality (Reis da Silva, 2024a). Older adults who experience loneliness may be more prone to adopting unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking, poor diet and sedentary lifestyle, further exacerbating their health risks (Reis da Silva, 2023b; 2024c).

Moreover, loneliness can negatively affect functional independence and quality of life in older adults. It may erode self-esteem, confidence and sense of purpose, leading to decreased engagement in social activities and withdrawal from meaningful relationships (Reis da Silva, 2024a). Loneliness can also impair sleep quality, immune function and overall resilience to stressors, further compromising older adults' ability to cope with life's challenges (Reis da Silva, 2025c; 2025d).

Conclusions

All people are impacted by the ubiquitous and detrimental state of loneliness, which has a detrimental effect on their health and wellbeing. The majority of academics concur that it is a subjective and widespread issue that every person will experience at some time in their lives, despite the fact that there is no universal agreement on its theoretical underpinnings (Tzouvara et al, 2015). Further conceptual and theoretical work is needed to avoid or lessen loneliness, especially in defining and analysing its effects in various social and cultural situations. When loneliness lasts long enough to result in a recurring pattern of unfavourable feelings, ideas and behaviours, it becomes a significant worry (Cacioppo and Patrick, 2008).

Enhancing social skills, augmenting social support, expanding social engagement opportunities and treating maladaptive social cognition are the four main therapeutic options suggested (Masi et al, 2011; Hemingway and Jack, 2013). However, as loneliness becomes chronic, it becomes more difficult to put these methods into practice. Loneliness is also more common in poor health; over half of women with multiple sclerosis (Beal and Stuifbergen, 2007) and 45% of elderly patients with chronic diseases report feeling alone (Kempton and Tomlin, 2014).

Loneliness represents a significant public health issue, particularly among older adults. Its conceptualisation as a subjective experience of social isolation underscores the importance of addressing not only the quantity, but also the quality of social connections in older people.

By recognising and addressing the multifaceted impacts of loneliness on mental, physical, and social wellbeing, healthcare professionals can develop more effective interventions and support systems to mitigate its adverse effects and promote healthy ageing and meaningful engagement in later life.