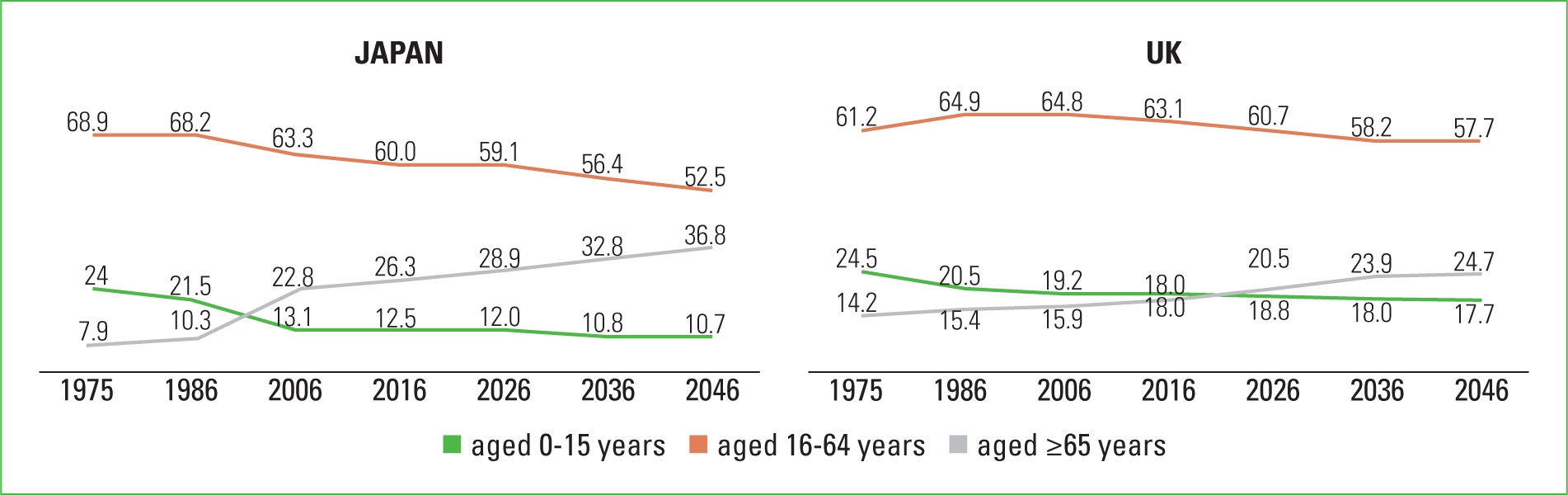

As the total fertility rate continues to decline in Japan, the proportion of its population aged ≥65 years is expected to reach 36.8% in 2046 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2021). Japan's super-aging society is unparalleled in the world, as reflected by the proportion of the population aged <15 years (12.1%), 15-64 years (59.3%), and ≥65 years (28.7%) in 2020 (Cabinet Office, 2020). As a result, two major issues arise: the collapse of the benefit-burden balance of social security systems for medical and long-term care expenses due to the shrinking working-age population, and the decrease in quality of life (QoL) of older people due to the shortage of caregivers. To address this, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2021) promotes the establishment of an integrated community care system, allowing older people to continue living independently until the last stages of their lives.

The integrated community care system aims to prevent the worsening of an individual's care requirement status and promotes functional recovery in older people. In particular, mutual aid among local residents is recommended (Akiyama, 2016). To encourage older people to get out of the house and create purpose in their lives, volunteers play a central role in organising activities such as café salons, exercise classes and hobby group get-togethers. Yet, some housebound older people avoid group settings.

In Japan, the phenomenon of older people becoming housebound has been a social problem since the 1990s. ‘Housebound’ is defined as a ‘condition in which a person is unable to go out even though they are capable of doing so’ and ‘a state in which social relationships have been lost’ (Hatano and Tanaka, 1999). Recent studies have defined the housebound state as ‘not having left the house even once a week’ (Yasumura, 2006). According to one study, 8% of older people aged ≥70 years meet this definition (Sugisawa et al, 2012). This definition can be considered analogous to the definition of social isolation proposed by Peter Townsend (1957), which differs from that of social loneliness. Houseboundness is reported as a risk factor for an individual shifting to a need-for-support/care state from being bed-ridden due to muscle weakness (Shinkai et al, 2005). One study reported that active support may improve the condition, offering the opportunity to revert back to a non-housebound state (Yamazaki et al, 2008). In this context, welfare commissioners are tasked with conducting individual visits to identify housebound older people early and connect them to support.

The welfare commissioner system in Japan is an informal welfare system that is offered free of cost. The characteristics of welfare commissioners are as follows (Kobayashi, 2020):

- According to the Welfare Commissioners Act:

- - the welfare commissioner needs to comply by the rules such as confidentiality, fair activities, and the officer cannot use their position politically

- - It is mandatory to carry out activities responsibly

- Work without compensation

- - Because no compensation is provided for activities, it is easy to ask for cooperation from surrounding people

- Do not belong to a specific business operator, etc.

- - They take a fair and neutral stance

- Chosen from among local residents

- - They know the state of the community, so it is easy to monitor the living conditions of local residents.

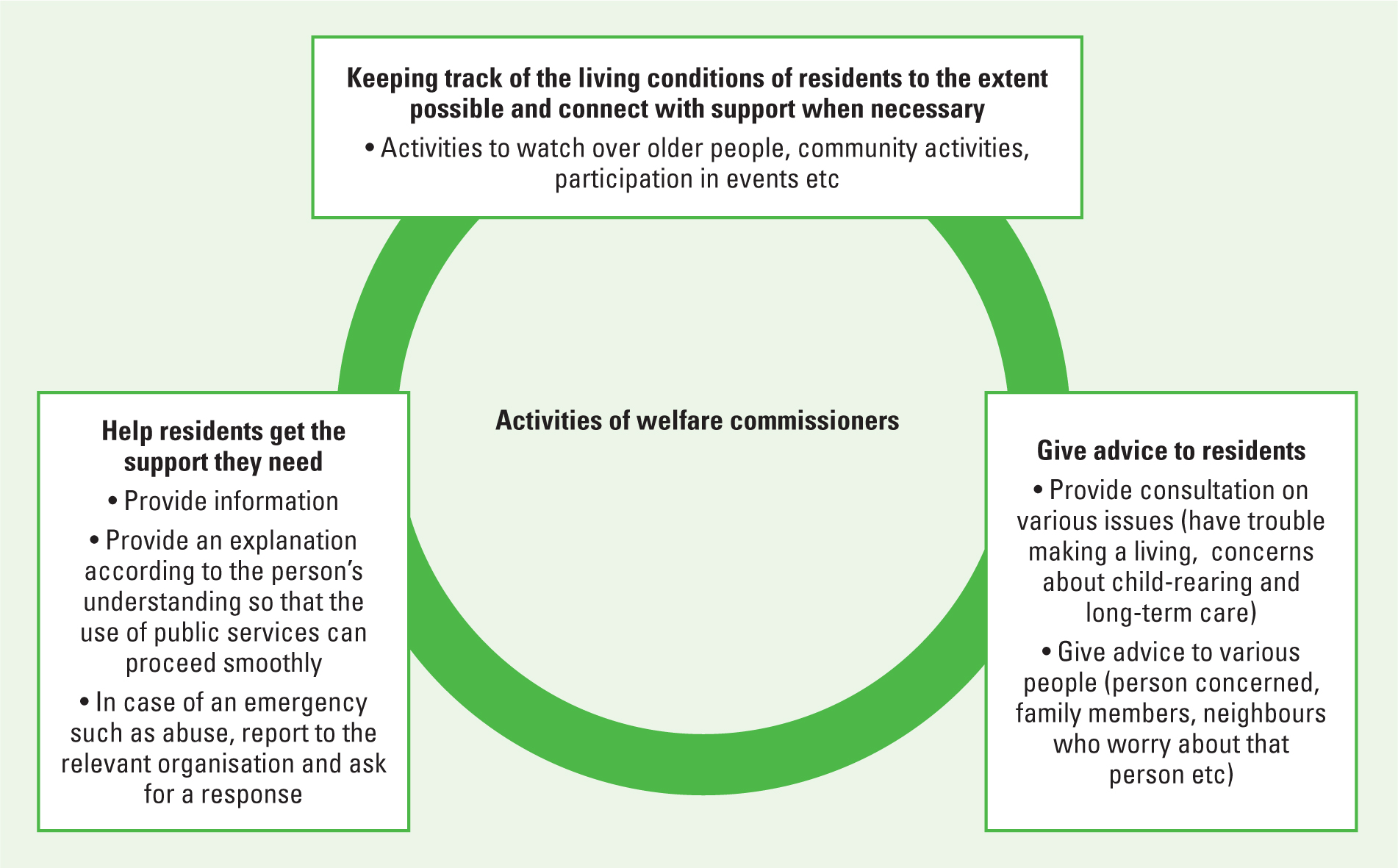

As a representative formal system in Japan, long-term care insurance provides support for the home care of older people. Services such as visiting nurses and helpers are available for a fee, but there are no services similar to the activities provided by a welfare commissioner. Currently, there are approximately 230 000 welfare commissioners in Japan (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2015), and each welfare commissioner makes an average of 136 home visits per year in the area to which they are assigned (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2015). The community association or town council selects qualified individuals, and as local public officials in a special position commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (3-year term with possible reappointment), they serve as consultants to whom local residents can easily turn to for free advice. Being a welfare commissioner is not a full-time job, and some work other jobs. Welfare commissioners are volunteers who offer their extra time. Figure 1 summarises the roles of welfare commissioners in supporting residents (National Federation of Welfare Commissioners and Commissioned Child Welfare Volunteers, 2016). The government periodically holds workshops to improve the quality of welfare commissioners.

Some local residents are not aware as to where they must go when problems arise, whom they should talk to, or in what way. In Japan, where the welfare system, in principle, requires a person in need of assistance to file an application to the municipality, welfare commissioners are expected to function as front-line agents in outreach efforts. However, the percentage of housebound older people that welfare commissioners are aware of is low, at about 1.4% according to one study (Sugisawa et al, 2012). While local resident-led support efforts geared to older adults are hindered for various reasons, few studies have investigated these in detail.

The present study involved a qualitative analysis of issues relating to support activities aimed at preventing older people from becoming housebound through mutual aid among residents, with a particular focus on individual visits by welfare commissioners. Our findings offer basic information that can be used to examine the support system led by local residents to prevent older people from becoming bedridden.

Demographic changes in the UK are similar to those in Japan (Figure 2), with age percentages expected to approach those in Japan in a few decades. In this sense, issues identified here regarding welfare commissioner-led support for older people may also apply to the development or assessment of a similar system in the UK.

Methods

Study design

To clarify participant experiences, this study used a qualitative descriptive study design (Kayama, 2007)—a widely used method that reveals reality from an insider's perspective. Qualitative descriptive research focuses on the description of phenomena and describes them in everyday language (Kayama, 2007). Semi-structured interviews were conducted using community health nursing diagnosis, a method proposed to be useful for understanding the care needs of local residents (Kanagawa and Tadaka, 2011).

Study regions

This study was conducted in two cities, Habikino City (population: 109 565) and Izumiotsu City (population: 73 432), which are located in the suburbs of Osaka, one of the largest cities in Japan. Both cities have new residential areas as well as areas where long-established residents live. Compared with Japan's average aging rate of 28.0%, the rate in Izumiotsu City is low (25.7%), whereas that of Habikino City is high (30.6%) (Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2021).

Participants and data collection

Participants were welfare commissioners who make individual visits to older people in the respective regions. In both cities, 17 welfare commissioners (seven males, 10 females) were selected by welfare officers in the department that oversees welfare commissioners. All welfare commissioners provided consent to participate in this study. The average number of years of experience carrying out welfare commissioner activities was 9.7 years (range: 3–15 years). Between January and March 2021, researchers conducted semi-structured interviews lasting between 30-90 minutes, with participants using an interview guide. The purpose of the interviews were to gain an understanding of welfare commissioner activities. Interviews were initiated using the following types of questions based on previous studies (Aida and Kondo, 2014; Yoshiyuki and Kono, 2020): 1) What do you find difficult when carrying out individual visits? 2) Are there any cases for which you were able to improve housebound status? 3) Is there anything you keep in mind when communicating with housebound older people? 4) Do you do anything to modify the setting that promotes older people to leave the house? 5) Do you feel that community ties have weakened?

Interviews were conducted in a private room in the city hall, audio-recorded, and then transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Verbatim transcripts were divided based on content similarity, and segments with content pertaining to issues related to support for housebound older people were assigned codes. Categories were created based on the generated codes and grouped from the perspectives of ‘problems,’ ‘strengths,’ and ‘measures’ related to support for housebound older people. During these analyses, researchers specialised in qualitative analysis were invited to participate in data analysis. Member-checking was also performed and expressions were modified with appropriate to more suitable alternatives.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the affiliated university.

Results

Issues related to support to prevent older people from becoming housebound

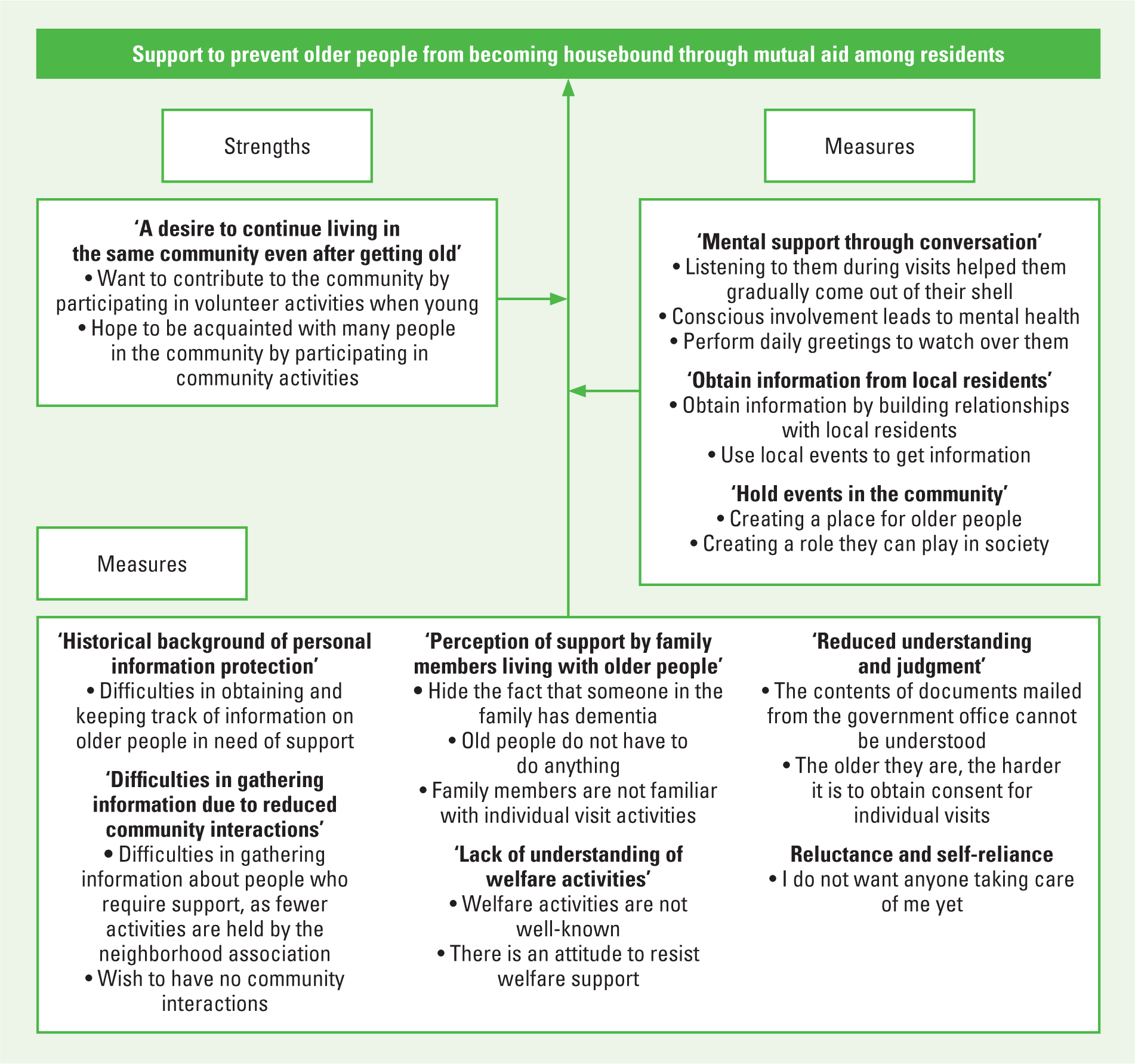

As there were no significant differences in data between the two cities, aggregated data from both cities were subjected to analysis (n=17; seven males, 10 females). In total, 72 codes were extracted from the data and 20 subcategories were created. From these, the following categories were identified as ‘problems’, a ‘strength’, and ‘measures’ when performing individual visits with older people: ‘Perception of support by family members living with older people,’ ‘Difficulties in gathering information due to reduced community interactions,’ ‘Historical background of personal information protection,’ ‘Reduced understanding and judgment,’ ‘Lack of understanding of welfare activities,’ and ‘Reluctance and self-reliance’ (problems); ‘A desire to continue living in the same community even after getting old’ (strength); and ‘Mental support through conversation,’ ‘Obtain information from local residents,’ and ‘Hold events in the community’ (measures). Figure 3 presents categories in ‘quotes’ and subcategories in (square brackets).

Problems faced when carrying out individual visit activities

‘Perception of support by family members living with older people’

Given the prejudice that people with dementia disturb others (e.g. behave violently, become confused/disoriented), some people hide the fact that there is someone with dementia in their family. In addition, the subcategory (old people do not have to do anything) suggested that concern for old parents (e.g. feeling bad about making them do things) was preventing them from going out.

‘Difficulties in gathering information due to reduced community interactions’

Relative to the past, fewer households now rely on neighbouring groups to organise ceremonial functions. For reasons such as a lack of clarity regarding residents' family structures, welfare commissioners encountered difficulties in gathering information about people who require support, as fewer activities are held by the neighbourhood association. An increasing number of people do not wish to reveal their occupation or family information to neighbours, and many wish to have no community interactions.

‘Historical background of personal information protection’

Since the enforcement of the Act on the Protection of Personal Information in 2005, administrative institutions are required to obtain consent if they wish to submit personal information to welfare commissioners. Participants responded that there are difficulties in keeping track of information on older people in need of support; for example, because they cannot obtain consent from all older people.

‘Reduced understanding and judgment’

Government offices send documents to older people to confirm their wishes for welfare commissioners' visits. However, in some cases, reduced understanding and impaired judgment due to aging resulted in a situation where the contents of documents mailed from the government office were not understood. Furthermore, the older they are, the harder it is to obtain consent for individual visits.

‘Lack of understanding of welfare activities’

As suggested by the subcategory, ‘welfare activities are not well-known’, some older people do not trust welfare commissioners even when they identify themselves and refuse to invite them in when they visit. This issue was also reflected by the subcategory ‘there is an attitude to resist welfare support’. For example, some older people are uncomfortable about being taken care of by welfare commissioners because of the prejudice associated with the origin of the welfare commissioner system, that is, relief work for the poor.

‘Reluctance and self-reliance’

As suggested by the subcategory ‘I do not want anyone taking care of me yet’, some welfare commissioners were told by older people that they want to do their best on their own to the extent possible.

Strengths relating to support to prevent older people from becoming housebound

‘A desire to continue living in the same community even after getting old’

Some responded that they want to contribute to the community by participating in volunteer activities when young, so that they can receive assistance from people in the community when they become older. Others noted that, as they wish to have people in their community watch over them in their old age, they hope to be acquainted with many people in the community by participating in community activities.

Measures to prevent older people from becoming housebound

‘Mental support through conversation’

Some shy older people may still enjoy talking. The subcategories ‘listening to them during individual visits helped them gradually come out of their shell’ (e.g. ‘I made home visits twice a month to chat for about 5 minutes at the front door, and they gradually started to talk to me’) and ‘conscious involvement leads to mental health’ (e.g. ‘They tell me happily that I came by to check on them’; ‘They tell me that, although they do not like socialising, they are glad that welfare commissioners started visiting to chat with them’), were included in this category. Some responses were related to the subcategory ‘perform daily greetings to watch over them’ (e.g. ‘I greet older people in my neighbourhood whenever I see them at a supermarket’).

‘Hold events in the community’

Welfare commissioners worked on creating a place for older people and creating a role they can play in society in cooperation with volunteers by holding monthly activities for local residents, such as café salons, plays, and dinner parties within walking distance.

‘Obtain information from local residents’

In circumstances where the personal information protection system made it difficult to obtain information using official channels, an alternative method was used by welfare commissioners to obtain information by building relationships with local residents.

Discussion

In this study, the authors interviewed welfare commissioners engaged in health support activities for older people in the community and identified issues in the efforts to provide support to prevent older people from becoming housebound. Our findings may serve as a reference for others wishing to construct a support system for older people through mutual aid among local residents.

At the community level, the authors found that it is more difficult to keep track of older people who live with their children than those who live alone. This finding is consistent with a study by Imuta et al (1998). Reasons for this include the tendency to hide the fact that there is someone with dementia in the family considering the stigma around dementia, as well as discomfort about their old parents going out or participating in neighbourhood association events out of consideration for their physical condition. These attitudes can negatively affect the remaining functions of older people. Moreover, family members with insufficient knowledge about the welfare commissioner system may refuse visits; this has been suggested as an obstacle in the path toward utilisation of the welfare system by older people. To this end, it will be important to disseminate information to local residents about the activities of welfare commissioners, both in terms of content and impact, so that older people living with their families can benefit from individual visits.

The authors also found that welfare commissioners and volunteers encounter difficulties in obtaining and keeping track of information about the support received by recipients. This issue reflects an environment in which the protection of personal information is emphasised and is exacerbated by a generation that wishes to have no community interactions. Japan has a system where residents voluntarily join their neighbourhood association and pay association fees. The association uses the collected fees to carry out community activities, such as ceremonial functions, Bon dances (a style of dancing performed during the festival of Obon), and sports events. These activities offer opportunities for residents in the neighbourhood to engage in community interactions, thereby deepening their relationships. However, in recent years, the number of people who participate in events organised by neighbourhood associations have decreased, and fewer households join the associations, which tend to primarily comprise younger households. At the root of this decrease is an aversion to having neighbours intrude upon their privacy. The result is reduced interactions among residents in the community, which makes it difficult for those who provide support to gather information on older people who may need it.

To address this issue, welfare commissioners take the initiative by approaching local residents to obtain information on older people in need of support. They also make efforts to engage in conversations with older people through individual visits or by proactively talking to them when they run into them in places like the supermarket on a regular basis. Furthermore, to prevent physical frailty among older people, welfare commissioners, together with volunteers, provide places where older people can visit, such as café salons, theater clubs and dinner parties.

Causes of houseboundness among older people include physical aspects such as weakness due to aging, mental conditions such as feelings of isolation and anxiety, and changes in one's living environment. Lower self-efficacy is another factor (Yamazaki et al, 2016). Our findings suggest that individual visits and daily greetings by welfare commissioners can increase self-efficacy and help revitalise the lives of older people in general and are thus effective support measures for preventing houseboundness in older people. The authors also identified confidence in one's neighbours as a strength for building support systems (e.g. ‘if I participate in community activities from a young age and make many acquaintances in the community, they will watch over me when I get old’). Residents who are actively involved in volunteer activities contribute to the development of local support systems by enhancing the community's ability to solve problems (Yamauchi, 2010). Support that leverages this strength to enhance mutual trust among local residents is also important.

One limitation of this study is that the issues the authors identified were those perceived by welfare commissioners. Although welfare commissioners are key individuals who provide support for older people through mutual aid among residents, the present results might not be generalisable. Future challenges include obtaining an accurate picture of the actual state of support for older people and further confirming the findings obtained in this study.

Conclusion

Since around 2005, when the proportion of people aged ≥65 years exceeded the proportion of those aged <15 years in Japan, resident-led efforts to support older people in the community were initiated to mitigate problems that were expected to occur with the progressive aging of the population and declining birthrate. This study revealed that individual visits by welfare commissioners can provide psychological support to older people who have a tendency to become housebound, as well as those who refuse to participate in group settings. The authors also found that this relationship among residents that facilitates knowledge of where older people live, what their family structures are, and what health state they are in is key to an effective support system for older people through mutual aid among residents. In recent years, community care has tended to focus on individual support for older people. However, to provide better support, efforts to create a local environment where people of all ages living in the community are acquainted with each other are important.

Key points

- As Japan faces super-aging of their population, establishment of systems to support the health of older people through mutual aid among local residents has been promoted. Welfare commissioners play a central role in providing such support under the welfare commissioner system

- For older people who tend to be housebound and resist participating in places where crowds gather, welfare commissioners make individual visits in order to prevent mental frailty through conversation

- This study revealed that older people living with their children are harder to keep track of at the community level than those living alone.

CPD reflective questions

- What are some of the problems faced by local residents as they watch over older people? What measures need to be taken to address this?

- Why are older people living with their children harder to keep track of at the community level than those living alone?