The increase in dementia and Alzheimer's disease presents a global challenge. The number of people currently living with dementia globally is estimated at 55 million (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021) and fuelled by an ageing population. This number is set to grow to 150 million by 2050 (Stavropoulos et al, 2020). Dementia is a debilitating and incurable disease resulting in a progressive loss of independence. Over 70% of those living with dementia cannot live independently without caregiver assistance (Stavropoulos et al, 2020).

In the UK, caring for dementia patients currently costs £26 billion a year and these costs will grow alongside the predicted growth in dementia cases (Oskouei et al, 2020). A significant proportion of this cost is from hospital admissions. Emergency hospitalisations for people over 65 years with dementia are much higher than those people without (Sommerlad et al, 2019). It is estimated than one in four hospital beds in the UK, catering to older acute adults, are occupied by a person with dementia (Lakey et al, 2012). It is estimated that 20% of all hospital admissions of people living with dementia are preventable (Public Health England, 2015), with urinary tract infections being one of the five leading causes of hospitalisation for people with dementia (Scrutton and Urzi Brancati, 2016). Hospitalisation for dementia patients usually results in irreversible decline (Shepherd et al, 2019).Thus, reducing preventable hospitalisations in dementia patients to preserve a higher quality of life is a key population health goal (WHO, 2017).

A focus on earlier identification and intervention would help reduce preventable admissions. However, current care pathways are dependent on the stretched, labourintensive human resource of care givers and healthcare professionals, who are unable to provide this proactive care on their own. Remote health care monitoring of patients, using intelligence gathered from Internet of Things (IoT) sensors coupled with analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, present a promising solution for remote monitoring, assessment and support. Several studies have demonstrated that these systems can alert patients and healthcare providers when an adverse situation arises, prolong independent living, reduce caregivers' burden and healthcare costs, while maintaining the patient's safety (Enshaeifar et al, 2018; Rostill et al, 2018).

Enshaeifar et al (2018) explored Technology Integrated Health Management (TIHM), which is a system leveraging Internet of Things (IoT) technology to continuously monitor individuals with dementia in their residences. They demonstrated promising intial results with the capability of the algorithm to recognise agitation and abnormal patterns with an accuracy rate of up to 80%. However, the study (12 participants) was limited in terms of numbers and not randomised, and so may not be representative of the target population. The clinical validation of the algorithm is not robust. For example, patients who may have had agitation, irritability or aggression, but did not show any evidence of this on the sensors, were not included in the analysis. This could have resulted in increased numbers of false negatives, thereby reducing the overall accuracy of the algorithm. There is also no external validation of the algorithm in other clinical sites, and overall, the description is very technical, not placing the clinical perspective in focus. Similarly, Rostill et al (2018) showed promising results in the use of IoT and AI to monitor dementia patients with more than 60% of the alerts generated by the technology being clinically relevant (true positive), with some interesting case studies where the technology allowed early intervention and the prevention of deterioration. However, false negatives are not considered due to the logistic and technical difficulties. None of the above four studies have looked at the patient outcomes in terms of parameters of their disease. They have also not looked at the workflow of the staff and how this has changed, especially in terms of their time resource of the whole patient pathway.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, remote monitoring technologies were utilised across England to help care for patients during social distancing measures. Between November 2020–May 2021, 78000 patients were supported by remote monitoring technologies for conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure (NHS Transformation Directorate, 2022). For community-based dementia patients in North Warwickshire, IoT driven remote monitoring technology was identified as a technology that could assist the nursing team in caring for their patients remotely; this was facilitated by South Warwickshire Foundation Trust (SWFT). This IoT driven remote monitoring technology was used from May 2020, with the dementia clinical nurse practitioner (DCP) leading the care pathway development.

The aim of this evaluation is to determine whether this technology-enabled service modification improved the efficacy and access to care provided for dementia patients and increased cost effectiveness. The authors present the initial evaluation results of this change in service and consider the relevance of this type of technology postpandemic in the context of virtual wards.

Methods

Cohort

This project served as a pilot initiative, wherein the community dementia team identified suitable patients. Subsequently, they engaged in discussions with both patients and families to gain their acceptance and willingness to participate in the project. Upon meeting the eligibility criteria, the remote monitoring sensors were installed for these eligible patients.

The inclusion criteria were:

- Patients suffering with dementia

- Living alone

- Maintaining independence

- Ability to comply with the installation requirements of the IoT sensors.

The final cohort consisted of 23 patients who met the above-mentioned criteria.

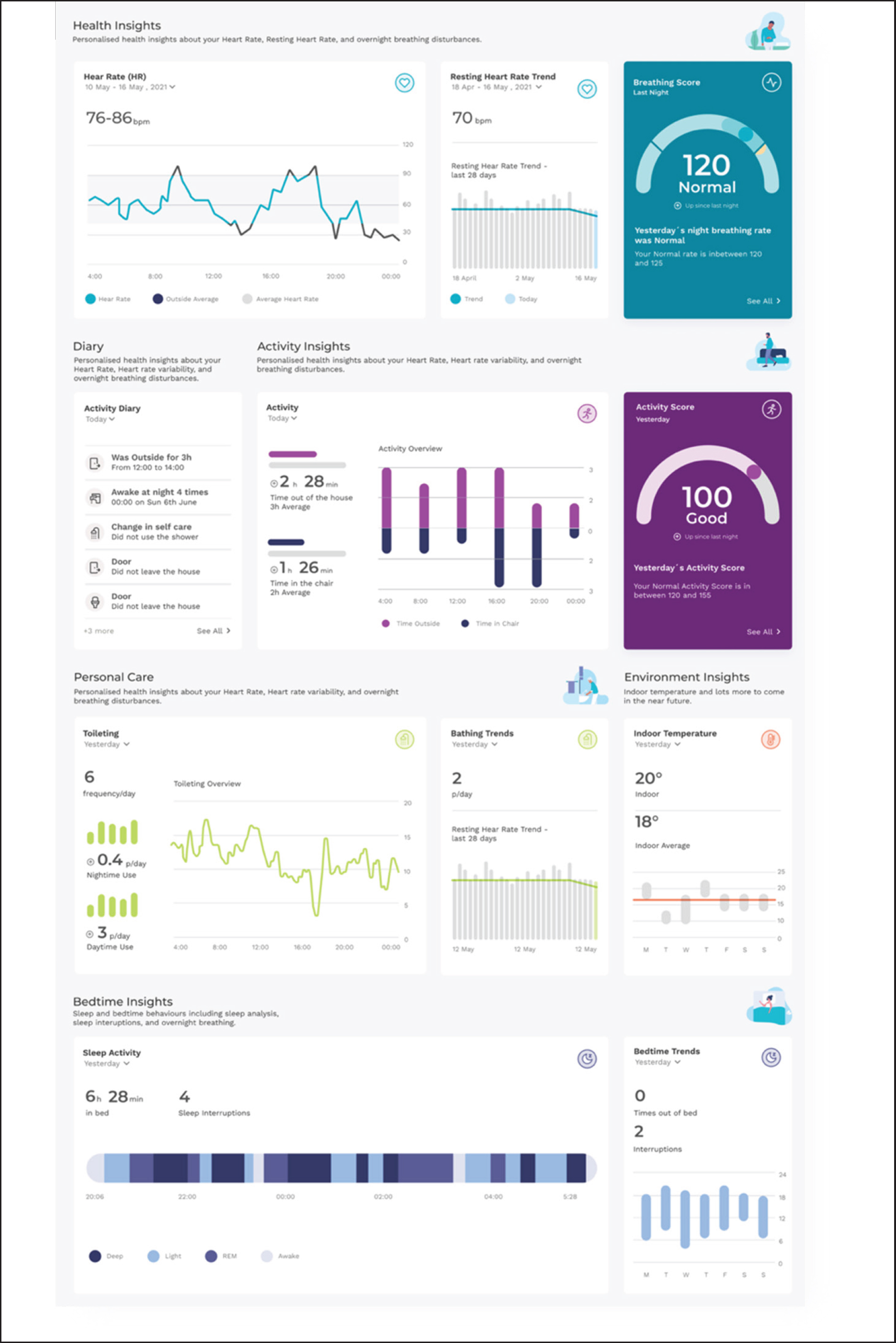

An Internet of Things-driven remote monitoring technology equipment and dashboard

The remote monitoring technology piloted collect approximately 10000 to 15000 data points each day using passive IoT sensors placed in key touch points in a person's home as they go about their normal routine.

The main sensors are as follows:

- The tap, toilet, chair, front door, bathroom door, fridge door and kettle sensors collect usage data

- The bed sensor collects information on the quality of sleep and time in bed.

Additional data is collected by a wearable device worn on the wrist collecting information on activity and heart rate. Data is then fed into a dashboard (Figure 1) via a central gateway where it can be accessed by healthcare professionals and displays a range of information including sleep patterns, nutrition, hydration, independence, activity and heart rate.

Within the system, an AI algorithm plays a crucial role in continuously analysing data and learning the unique patterns associated with each patient's normal routine, activity, and heart rate. By recognising these individual patterns, the AI becomes proficient in identifying any deviations or changes that might suggest a decline in the patient's health and promptly alerts the responsible clinician in such instances.

The clinician considers these changes alongside their professional knowledge of the patient and, when necessary, can coordinate a preventative intervention. For example, increased use of the toilet may signify an early urinary tract infection (UTI). The preventative action for the team would be to visit the patient and do a test for a UTI and start antibiotics, thus preventing admission for a UTI which is one of the most common causes of hospital admission for dementia patients.

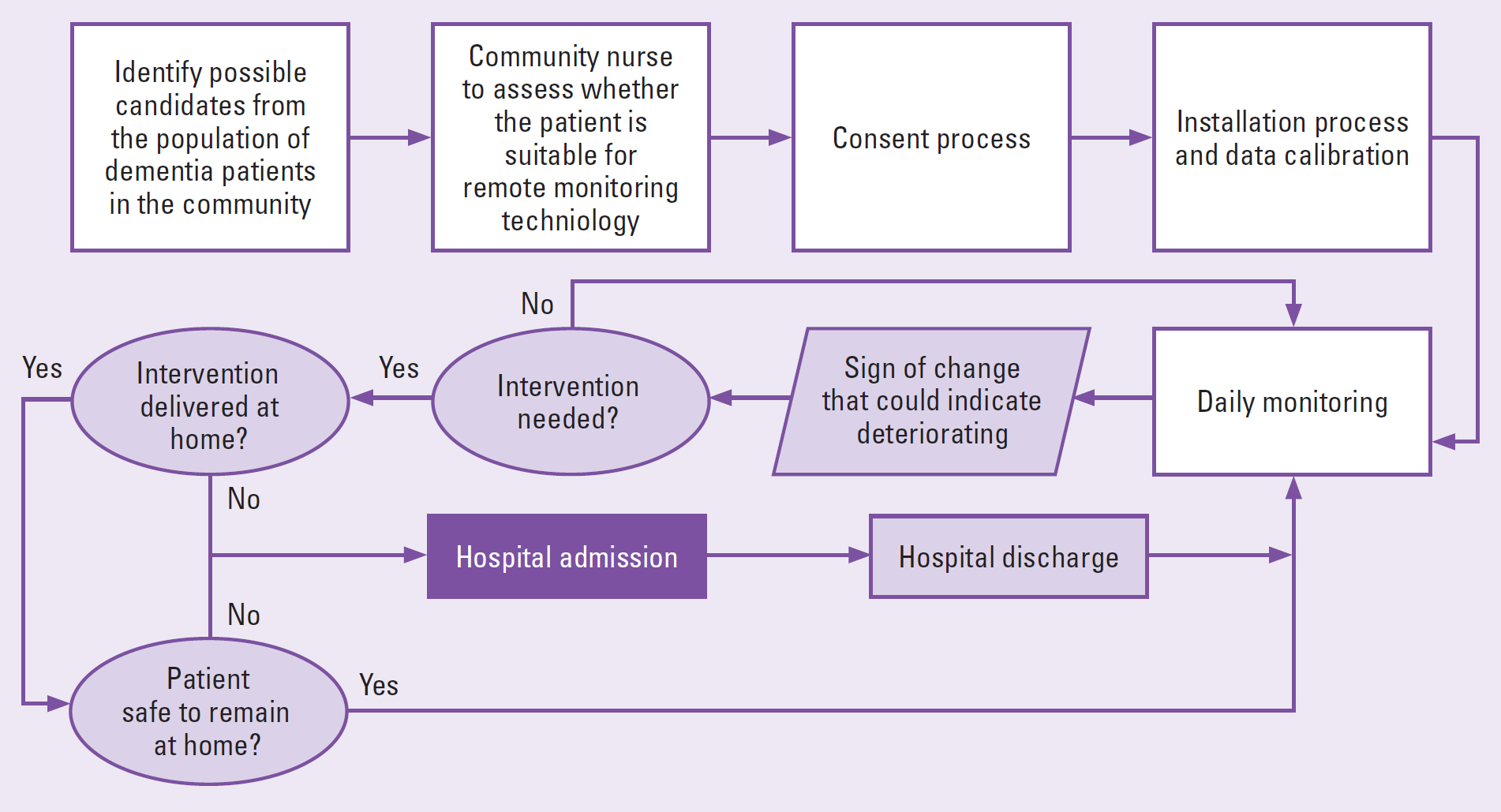

Using remote monitoring technology in the dementia care pathway

The DCP was assigned to lead the practice development of remote monitoring technology insights in the dementia care pathway. Figure 2 shows the process the DCP took from identifying a patient to be part of the pilot, to making an intervention.

Once this remote monitoring technology was successfully installed within the patient's home, the DCP would check the remote monitoring technology dashboard for new clinical and social insights each day, paying particular attention to heart rate and sleep data. Anomalies and changes in these patterns would trigger further investigation by the DCP through calling or visiting the patient. If an intervention was needed, this would be arranged by the DCP to prevent further deterioration.

Health utilisation data

Anonymised healthcare utilisation data during and prior to the installation of the IoT remote monitoring technology was collected for the 23 patients by the DCP from the patient management system EMIS. Healthcare utilisation data included urgent interventions, 111 call outs, GP contacts, 999 call outs, hospital admissions and referrals to the place based care team (PBT) who provide a range of nursing and therapy services in a person's home (Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust, 2021). The average period of use of the remote monitoring technology per patient was 28 weeks (four patients less than 13 weeks and six patients over 40 weeks). The time period of the patient data collected prior to the installation of the remote monitoring technology matched the time period during which the patient had the system installed. Across the cohort, 1298 weeks of data was collected and there were 464 instances of healthcare utilisation.

For the analysis, Excel was used first to calculate the difference between the utilisation of healthcare before and after the installation of the remote monitoring technology creating descriptive statistics. Using the number of instances of healthcare utilisation, a Chi Square test was performed using SPSS software to determine if there was any evidence of difference in the pattern of healthcare utilisation before and after installation of the remote monitoring technology.

Financial impact

To estimate the potential financial impact of the service change, a reference cost for each category of health care utilisation was found (Table 1). These average costs were then used to estimate the change in annual financial costs of healthcare utilisation for the cohort after the system change.

Table 1. Average cost estimates

| Category | Cost | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital admission | £3126.66 | NHS unit cost 2020–2021, average of nonelective long stay for ‘tendency to fall, senility or other conditions affecting cognitive functions, without intervention CC score − 0 3 ’ (NHS England 2021) |

| 999 call out | £292.00 | Cost of 999 call out with A&E visit (Kings Fund, 2019) |

| GP call out | £39.23 | PRRU unit costs for health and social care, patient contact with GP (average) (Jones and Burns, 2021) |

| 111 call out | £21.15 | NHS digital estimate, upper estimate cost of 111 clinical call back including clinical time (Turner et al, 2021) |

| PBT intervention | £102.00 | NHS unit cost 2020–2021, community health care for ‘Immediate Home-Based Care’ (NHS England, 2021). |

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The data is retrospective and anonymised. The participants agreed to the collection of data presented in this publication by signing the terms and conditions for use of the remote monitoring technology and their data was anonymised for analysis. This is a service evaluation, and we did not set out to perform research; therefore, full ethical approval was not needed. Ethics were discussed with the local director of research and development.

Results

Table 2 shows that there was a reduction in all areas of urgent health care: a 46% reduction in hospital admissions, a 43% reduction in 999 call outs, a 62% reduction in GP contacts and a 63% reduction in 111 call outs. This decrease in urgent care by 56% and increase in Place Based Team (PBT) care by 346% represents a shift to preventative care for the service. There were 153 less instances of urgent care and 45 more instances of preventative care across the patient group. This change in pattern of healthcare utilisation was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001) through a Chi-Square test.

Table 2. Heath utilisation for all patients before and after commencing MySense

| Type of healthcar utilisation | 111 call outs | GP contacts | 999 call outs | Hospital admissions | Urgent interventions | Place based care referrals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre install | 32 | 149 | 51 | 41 | 273 | 13 |

| Post install | 12 | 57 | 29 | 22 | 120 | 58 |

| % change | −63% | −62% | −43% | −46% | −56% | 346% |

| Pearson Chi-Square Test | p<0.001 | |||||

| 23 patients; 464 health utilisation data points | ||||||

Annual changes to cost of health utilisation

The reference costs set out in the methods section were used to calculate the estimated financial impact of the change to health utilisation. Table 3 shows that if the cohort accessed urgent services at the same rate to the period pre-installation, the resulting estimated annual total cost avoidance is £210 929. If the spending on PBT referrals of £9346 is considered, this total becomes £201 583. Table 4 shows that the annual estimated total cost avoidance per patient is £9171 and when spending on PBT referrals is considered, the total becomes £8764.

Table 3. Annualised change in costs for the whole cohort (23 patients)

| Type of healthcare utilisation | 111 call outs | GP contacts | 999 call outs | Hospital admissions | Place based care referrals | Urgent interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre install | £1334 | £12 266 | £33 918 | £294 897 | £2737 | £342 416 |

| Post install | £413 | £5425 | £14 792 | £110 857 | £12 083 | £131 487 |

| Change | −£921 | −£6842 | −£19 126 | −£184 040 | £9346 | −£210 929 |

Table 4. Annualised average change in costs per patient

| Type of healthcare utilisation | 111 call outs | GP contacts | 999 call outs | Hospital admissions | Place based care referrals | Urgent interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre install | £58 | £533 | £1,475 | £12 822 | £119 | £14 888 |

| Post install | £18 | £236 | £643 | £4820 | £525 | £5717 |

| Change | −£40 | −£297 | −£832 | −£8002 | £406 | −£9171 |

Discussion

The data collected indicates, as Stavropoulos et al (2020) suggest, that AI-powered platforms show promise as tools for healthcare staff. The additional patient insights from the remote monitoring technology gave an opportunity to increase proactive home-based interventions by 346%, thus significantly reducing the need for urgent interventions (−46% hospital admissions, −43% 999 call outs, −62% GP contacts, −63% 111 call outs). This is supported by strong statistical evidence (Chi-Square test (p<0.0005)) that the installation of the remote monitoring technology induced a change in the patterns of healthcare services utilisation.

This change shows significant promise for the improvement of outcomes for dementia patients. As there is no definitive cure for dementia,‘slowing decline, stabilisation and maintaining independent functioning’ become the most important goals in supporting people with dementia (Enshaeifar et al, 2018). Astell et al (2019) have suggested that the view of dementia should be expanded ‘beyond healthcare’ and people with dementia and their caregivers should have access ‘to devices, services and other tools to live as well as possible with their condition’.

Reducing urgent care resulted in significant annual cost avoidance, £201 583.39 for the cohort and £8764 per patient. It is estimated that 120000 people with dementia live alone in the UK, which is 14% of all those in the UK with dementia (National Institute for Health and Care Research, 2020). If the per patient change in urgent care costs shown in this article could be achieved for this group, this would result in a cost avoidance of over 1 billion per year (£1051739407). If a similar percentage of the 6625 people diagnosed with dementia in Warwickshire (Warwickshire County Council, 2022) also live alone, then there is a potential to reduce urgent care costs for 910 people, amounting to an estimated cost avoidance of £8133451. Although these figures need further investigation, they show the potential for healthcare technology to curb the predicted national growth in costs related to the growth of the population living with dementia (Oskouei et al, 2020).

As well as providing improved wellbeing for patients, the use of remote monitoring in the dementia care pathway reflects the current policy requirements and goals set for NHS England. The NHS is working to increase the number of virtual wards across England, aiming to create 40–50 virtual beds per 100000 population by December 2023. Evidence that the use of the remote monitoring technology can reduce healthcare utilisation shows that it can be a key digital tool in achieving a successful virtual ward model. However, the remote monitoring technology must be part of an armamentarium of digital tools that are seamlessly integrated at the point of care.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the only study that has analysed the effect of IoT on healthcare utilisation in this group of dementia patients and its financial impact on the system. Preliminary data from the study shows increased access to early care for dementia patients living on their own in the home environment. This is care they usually are unable to get as these early signs of deterioration would not have been picked up if the IoT system was not present. There is evidence that this early care then reduces admissions, thus significantly reducing the cost of care. This may then result in increased staffing costs of overseeing the IoT alerts, which has not been taken into account in the study analysis. However, if intelligence around these alerts was improved, then these increased staffing costs may be mitigated.

More study is needed to validate these findings in a larger, more diverse sample with comparisons to the current care models. But the clinical implications are that virtual wards and home care with SMART homes may become a new standard of care and way of life for dementia patients. Training of professional care workers will need to take this into account and this will become part of their routine way of working. Dementia care policies will need to adopt this as a recommendation of best practice as evidence grows.

Limitations and further studies

The data presented was captured in a ‘real life’ setting and shows some significant findings; however, there are limitations. The data was collected on a health service provider-level with a small cohort; therefore, further rigorous scientific study is needed to understand the impact of the remote monitoring technology on patients and health utilisation.

Although the reduction of hospital admissions and urgent healthcare utilisation is likely to be a positive result for dementia patients, no patient outcome measures were collected. There are challenges in measuring patient outcomes amongst dementia patients due to the degenerative nature of the disease. However, the collection of patient outcomes, such as quality of life, should be considered for future studies. It is also important to address concerns, as Vindrola-Padros et al (2021) have explained, that service models implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic when staff were redeployed to monitor patients remotely, might now become unsustainable as staff workloads increase.

Fully understanding financial impacts and costeffectiveness will also require deeper investigation. Models, such as a cost-comparison analysis, will need to be applied that consider the cost of the technology, cost of any changes to staff time and costs of system change. Crucial to the adoption of AI technology into clinical practice are health economic evaluations that can keep pace with and capture the complexities of AI innovation (Voets et al, 2021).

Seeing the potential of this technology, SWFT intend to expand the cohort of patients that use the remote monitoring technology across the trust. This will provide the opportunity to design a research study with a control arm that seeks to understand how this type of technology can reduce costs, improve patient outcomes, contribute to clinical decision-making and be seamlessly incorporated into care pathways to increase efficiency of staffing models.

Conclusion

The evidence presented shows that when insights from an AI powered IoT digital platform were used by nursing staff in the care pathway of dementia patients, urgent healthcare interventions including hospital admissions reduce, and preventative home-based interventions increase. It is estimated that this change in health utilisation achieve annual cost avoidance of £201583 for the cohort and £8764 per patient, representing a potential cost avoidance of 8.7 million per 1000 patients. Despite the limitations of the analysis due to scope and cohort size, these results show the potential positive impact of remote monitoring technology on the care of dementia patients with strong benefits from a provider utilisation perspective. Future plans to expand the cohort and include a control arm will create a larger data set and allow for more rigorous analysis. Future studies should consider cost-effectiveness in greater detail, patient health outcomes and the impact of technology on staff workflows and clinical decision making.

Key points

- Prevention of hospital admissions for dementia patients has the potential to improve patient outcomes and reduce costs and pressures for healthcare providers

- Remote monitoring technologies can help healthcare staff to identify and deliver interventions designed to prevent hospital admission, allowing patients to remain in their home setting

- The use of a specific Internet of Things (IoT) driven remote monitoring technology by specialist nurses in the care pathway of community-based dementia patients in North Warwickshire resulted in the reduction of urgent care utilisation and an increase in preventative care measures

- Changes in health care utilisation resulted in annual cost avoidance estimates of £201 583 for the cohort and £8764 per patient

- Further testing of this digitally enabled care pathway will seek to validate results and understand improvements to patient outcomes, levels of health utilisation and impacts on staff resource.

CPD reflective questions

- What is the value of reducing urgent health care for dementia patients?

- What are the challenges of researching preventative interventions with patients?

- What do you think the impact and challenges would be of using this technology within your practice?

- Do you think this type of remote monitoring would fit in to a virtual ward model?

- How could this model be applied to other clinical conditions and settings?