The number of people seeking help for mental health issues is rapidly increasing across both voluntary and statutory services (NHS England, 2021). There are several contributing factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the cost of living crisis and increased poverty (British Medical Association (BMA), 2023). This rising trend of mental health needs applies across the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, as well as the Adult, Older Adult and Specialist Mental Health Services (NHS England, 2021).

While it is recognised that this increase is in part due to a reduction in the stigma surrounding mental health problems (Henderson et al, 2020), services are unable to meet the current demand in a timely fashion. The most recent estimates suggest a waiting list at 1.2 million people (BMA, 2023); however, there is commitment to long-term planning, increased finance and service improvement, with an additional £2.3 billion a year pledged for mental health services by 2023/24 (NHS England, 2023a).

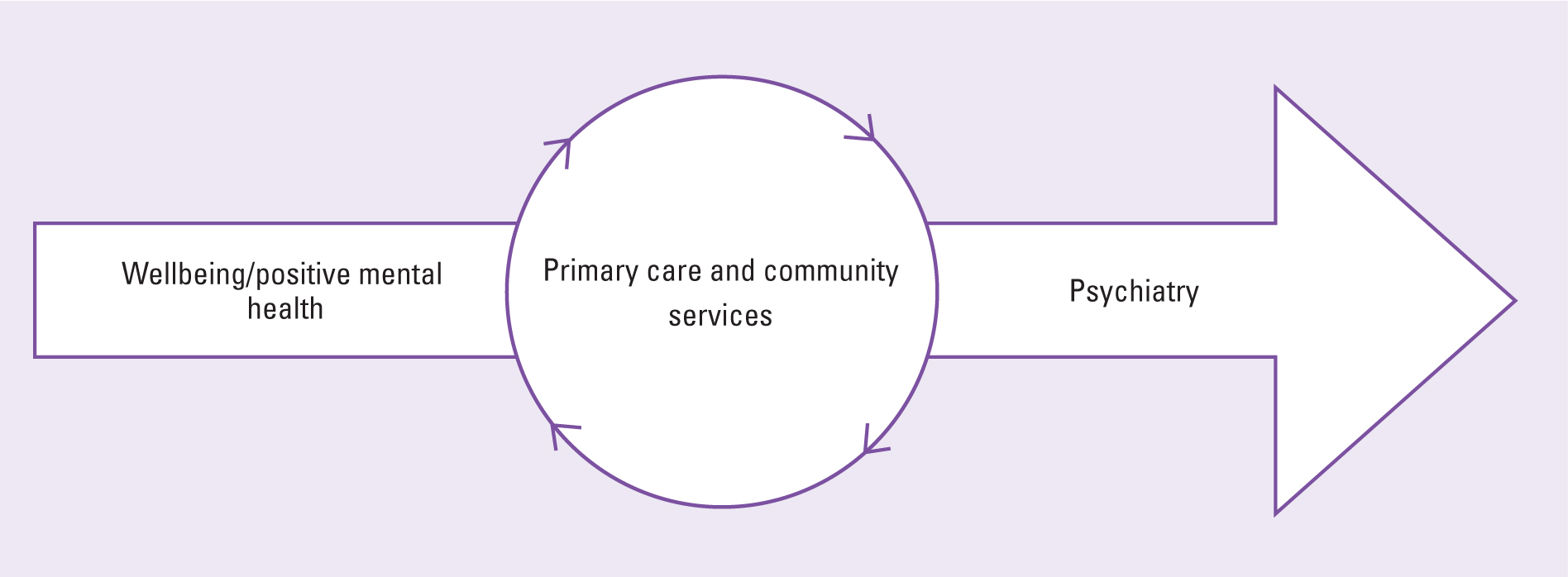

Perceptions of the meaning of ‘mental health’ appear to vary. The UK Government (2011) has provided a useful framework, with positive mental health being defined as ‘wellbeing’. Positive mental health/wellbeing has an impact on both mental and physical health and the two cannot be viewed in isolation (Clark and Clarke, 2014). It is anticipated that effective wellbeing services will result in a lower number of referrals to NHS mental health services at all levels (UK Government, 2011). Tertiary mental health services will continue to provide the care of those with mental illnesses/disorders under the medical supervision of psychiatry (UK Government, 2011). This move towards a ‘holistic’ or bio-psycho-pharmaco-social (BPPS) model of care (Clark and Clarke, 2014) has implications for healthcare professionals, and to some extent, wellbeing workers, as physical and mental health cannot be viewed in silos (Hext et al, 2018; Baker and Clark, 2020).

Over a decade after the UK Government (2011) asserted ‘no health without mental health’, this paper proposes a model to address the education and training needs of volunteers, mental health/wellbeing workers and healthcare professionals. Terminology will be clarified between wellbeing/positive mental health and mental illness/disorder, and the medical model of psychiatry.

Wellbeing

Wellbeing is defined as the combination of living functionally and feeling well (Huppert, 2009). While it is recognised within this definition that negative emotions and experiences are a part of life, wellbeing is preserved if these aspects do not have such an impact on a person's life as to interfere with their ability to function in day-to-day life. Thus, wellbeing can be considered synonymous with positive mental health. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines positive mental health as ‘a state of wellbeing in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’ (WHO, 2001).

Wellbeing services largely comprise services that involve non-healthcare workers (including the voluntary sector) who are fundamental in maintaining positive mental health in communities. These are the services where health promotion and prevention of both mental and physical illness should take place in order to prevent access to mental health services (Singh et al, 2022). Examples of these are a variety of counselling services via GPs, predominantly Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), workplaces, education, privately funded or voluntary organisations such as the Samaritans, Alcoholics Anonymous, Rethink, SANE, MIND, Young Minds and many more. The level of mental health training for these workers is generally unregulated and there is no clear guidance as to what training and education should comprise and what should be mandatory (Caulfield et al, 2019). This contradicts evidence highlighting the importance of empowering non-specialist health workers (Caulfield et al, 2019).

The increase in the number of people turning to non-healthcare workers such as health and wellbeing coaches has seen the subsequent growth of this aspiring profession (International Coaching Federation, 2023). This raises questions as to how regulated these individuals are and the nature and rigor of education and training that they have received (Aboujaoude, 2020). The evidence suggests that there is no specific or mandatory mental health education, training or assessment process involved (NHS England, 2023b).

In contrast, counsellors are considered a well-established profession that is regulated by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), with all counsellors and psychotherapists having graduated from a BACP-approved course to be able to register and display the BACP registered status (BACP, 2023). However, there is both full membership and accredited status of the BACP, with some members working towards registration through accreditation of required supervised hours, so that some ambiguity remains.

The Department for Education (2020) encourages schools and colleges to promote positive mental health and wellbeing. Teachers, teaching assistants, university and college lecturers, and academic staff in general have no requirement to receive mental health training, which is only implemented at the discretion of the school, college or university governing body or the headteacher/principal.

This lack of basic mental health training for the wide range of individuals working in wellbeing services may inevitably lead to an increase in referrals to mental health professionals at a later stage. There appears to be very limited ability to identify the early signs of physical or mental health illness or to conduct accurate and rigorous risk assessments (Singh et al, 2022). Further, organisations involved in the care and education sectors that commit to basic mental health training for their staff often rely on courses of a 1- or 2-day duration, some of which are online, with no exposure to in-depth case studies and real-life experiences. One example is the Mental Health First Aid training (MHFA) (MHFA England, 2024). While such courses raise awareness among staff as to what the issues are for people experiencing mental health problems, they do not equip individuals with specialist mental health fundamentals such as triage assessment or risk assessment/management skills.

Primary and community care for mental illness

Mental illness/disorder is defined in the International Classification of Diseases (WHO, 2019) as: ‘a clinically recognisable set of symptoms or behaviours associated in most cases with distress and with interference with personal functions’. General pracitioners (GPs), community and practice nurses, health visitors and social workers provide a vital bridge between wellbeing and tertiary mental health services, where more serious and enduring mental illnesses/disorders are managed and treated within psychiatric services during acute episodes. It is important to note that most mental illnesses/disorders are managed and treated in the community by GPs, Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and Home Treatment Teams (HTTs). Only the most unwell receive treatment in acute in-patient mental health facilities, while HTTs provide an acute and intensive service in the patient's own home for a limited time. Waiting lists for CMHT referrals are at a record high, which places added responsibility and increased workload on to already over-stretched community nursing teams, particularly regarding the care of older adults (NHS England, 2019).

At present, 18.6% of the UK population is aged 65 years or older and they comprise a large proportion of the community nursing caseloads. This has risen from 9.2 million (16.4% of the population) in 2011 to 11 million (18.6%). In the next 50 years it is predicted that there will be an additional 8.4 million people aged 65 years or older (Office for National Statistics, 2021). The risks associated with increased age are well documented and include increased physical health problems and multiple comorbidities; chronic pain; poly-pharmacy and consequent side-effects; change in relationship status and independence; loss of mobility and flexibility; change in work and financial status; and social isolation (Jaul and Barron, 2017). Such issues are congruent with compromised mental health status (Baker and Clark, 2020). There were about 1.4 million older adults who were chronically lonely and isolated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Age UK, 2020). It is important to note that the impact of the pandemic and imposed social restrictions, which were far-reaching, remain on-going with both physical and mental health dimensions for many older adults (WHO, 2022). This group of individuals are less likely to seek help for their mental health needs, and in many cases, are suffering from a significant level of diagnosable mental illness (Baker and Clark, 2020).

Pre-registration nurse education programmes for registered nurse (RN) (adult) students provide only a minimal level of mandatory component in the care of people with either mental illness, learning disability, or both (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2023). The standards for competency for RN (adult) state that they must be able to recognise and respond to the needs of all people who come into their care including babies, children and young people, pregnant and postnatal women, people with mental health problems, people with physical disabilities, people with learning disabilities, older people, and people with long-term problems such as cognitive impairment (NMC, 2021). It is contestable whether the standards of competency are achieved by the time of nurse registration.

Complex presentations

Mental illness is seldom straight forward or ‘text book’ in its presentation, with complexity added through a myriad of physical co-morbidities including long-term conditions, dementia, physical and/or emotional trauma, endocrine disorders and/or neurodiversity (Bahorik et al, 2017). Diagnostic overshadowing (whereby signs and symptoms are ignored and attributed to the primary condition) is a very real issue in more complex patients. Advanced assessment skills, knowledge and expertise are required to avoid diagnostic overshadowing and subsequent issues surrounding patients who have dual or multiple diagnoses (Ajibade, 2021).

For many years, the health care of people with learning disabilities, including their mental health has been the responsibility of generic NHS services (Department of Health, 2001; National Insitute for Health and Care Services, 2016) with specialist services at a minimum. This patient group often provides challenges to clinicians at all levels due to physical co-morbidities, diagnostic overshadowing and challenging behaviour (Care Quality Commission, 2017; Baker et al, 2020). This may lead to more serious mental health issues being unrecognised or diagnosed at each stage of the mental health journey. A lack of training and education for mental health/wellbeing workers, community nurses and even CMHTs results in less than optimum care for minority groups (Clark et al, 2017). The importance of understanding the limitations of one's own scope of practice at all levels cannot be over-emphasised (NMC, 2021).

Education and training needs

Wellbeing services

The growing waiting list for NHS mental health services necessitates a call for the implementation of a standard education and training framework for mental health/wellbeing workers. Teachers, counsellors, voluntary organisations and IAPT therapists should be able to carry out basic risk assessments if an adult or child presents with potential mental health needs, making appropriate referrals in a timely fashion (Clark et al, 2017).

The BPPS (bio-psycho-pharmaco-social) model may be used as an initial triage tool. It is a recognised and widely utilised approach for the assessment of both physical and mental health (Clark and Clarke, 2014; Hext et al, 2018; Baker and Clark, 2020). The model takes into consideration four aspects of health: biological, psychological, pharmacological and social – both at an individual level and in interaction with the given environment. Using this model at an early stage of the patient's journey, professionals in various settings would be able to make an initial assessment of the presentation of the individual. Appropriate education and training regarding common conditions and when to refer could inform a decision following assessment.

Education and training should be given in the identification of individuals who have suffered psychological and/or physical trauma, which may or may not always be known to mental health/wellbeing workers initially. Research shows that individuals who have suffered any kind of trauma are particularly at risk of further trauma and mental illness/disorder as a result (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US), 2014).

Mental health/wellbeing workers should also be expected to be confident in the delivery of evidence-based health promotion because overwhelming evidence stresses its importance in the prevention of mental and physical illness (Singh et al, 2022).

All mental health/wellbeing workers involved in delivering psychological therapies should be able to recognise the first signs of mental and physical illness and when help should be sought, as mental health needs fall outside of their scope of practice. The difference between counsellors, coaches and psychotherapists continue to be discussed in the literature (Jordan and Livingston, 2013). It is the responsibility of those practitioners involved to ensure that they are adhering to national standards, are clinically competent in their scope of practice and able to refer to specialists when necessary.

Primary care and community teams

Calls have been made throughout the years for a mandatory component of continuing professional development (CPD) in the care of patients with mental health problems and/or learning disabilities for RNs (adult) (Hicks and Clark, 2011; Clark et al, 2017; Hext et al, 2018; Xyrichis et al, 2018; Baker and Clark, 2020). However, this remains at the discretion of individual employers and there is still no mandatory requirement from the NMC to address this (NMC, 2021).

The demise of the ‘dual trained nurse’ (nurses with both Adult and Mental Health NMC registration) has occurred over recent years, indicating the need for RN (adult) to have a greater level of mental health education at both pre- and post-qualification levels, and vice-versa for RN (mental health) (Hext et al, 2018). Anecdotal evidence suggests that education in mental health for RNs (adult) at all levels varies across universities and NMC curriculum requirements are subject to differing interpretations.

There has been guidance over the years to enable high-quality patient care and enhance the professional development of a wide selection of healthcare professionals through competency frameworks, such as in multiple sclerosis (While et al, 2007), diabetes (Trend UK, 2015), learning disability care for adult nurses (While and Clark, 2014) and midwives (Beake et al 2013), learning disability care for mental health nurses (Clark et al, 2017) and clinical research staff (Manalo et al, 2020). Issues regarding education and training across the wellbeing and mental health continuum would suggest the need for the development of assessed competency frameworks by relevant professional bodies at each level of the continuum.

Table 1 outlines a benchmark of areas for competency development across wellbeing, primary care, CMHTs and HTTs. It is based on competencies for HTTs (King's College London with South West London & St George's Mental Health NHS Trust, 2013) which were developed utilising the standard process of a literature search, focus groups and a pilot study prior to successful implementation (While et al, 2007) across several London HTTs and have been only minimally adapted for this purpose.

Table 1. Benchmark of areas for competency development across wellbeing, primary care, community mental health teams and home treatment teams

| Wellbeing/positive mental health | Primary care and community teams | Community Mental Health Teams and Home Treatment Teams |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Conclusion

A decade on from ‘No health without mental health’ (UK Government, 2011), it is concerning that many of those working in wellbeing services with vulnerable people of all ages in the UK remain unregulated. These workers are considered key for health promotion and the prevention of both physical and mental health illness/disorder (UK Government, 2011). National professionally regulated standards that include robust training in health promotion and prevention, triage assessment and recognition of the first signs of mental and physical illness should apply to all those working in the plethora of wellbeing services.

Primary care and community teams serve as a bridge between wellbeing and tertiary psychiatric services and should conform to a set of professionally approved standards regarding the care of patients with mental health and psychiatric problems. Regular education and training updates should be provided as a component of a mandatory curriculum. Primary care and community teams provide the vital link for patients once they are well enough to be discharged from tertiary in-patient psychiatry and return to community and wellbeing services in its many forms.

Primary care and community teams have the key role of maintaining a steady, constant flow between the three key stages of mental health care (Figure 1). Wellbeing/positive mental health services should serve as a foundation and support for more specialist NHS mental health care, but this can only be achieved if investment is made into professional regulation, education and training through competency development.

Key points

- Referrals to mental health services are rising

- Wellbeing/positive mental health and mental illness/disorder are on a continuum

- Good wellbeing services can help reduce physical and mental illness

- Not all wellbeing workers are professionally regulated

- Primary and community care provides the bridge between wellbeing and psychiatry

- Education/training through a competency framework is needed across the continuum.

CPD reflective questions

- When did you last receive mental health education or training?

- Reflect on patients whom you have seen with mental health/psychiatric problems and how this challenged you

- What are your learning needs and how can you address them?

- Reflect on what would be key to improving wellbeing and mental health services across the continuum.