Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) plays an essential role in DNA synthesis and red blood cell production. Deficiency is a global health issue, often underdiagnosed because of its variable clinical presentations. While Vitamin B12 deficiency is a well-known cause of megaloblastic anaemia, its association with pancytopenia and haemolysis is less commonly recognised, leading to potential misdiagnosis (Remacha et al, 2011). The condition predominantly affects populations with limited intake of animal-derived foods (Green et al, 2017). Globally, the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency varies, ranging from 2.5% to 60.0% depending on the population studied (Al-Musharaf et al, 2020). In Africa, the prevalence is estimated to be higher; some studies have reported rates of up to 70% in certain regions (Melaku et al, 2024). Specifically in Uganda, studies have shown a vitamin B12 deficiency prevalence of 10.7% among adults, with higher rates observed in rural areas and among individuals following plant-based diets (Kwape et al, 2021).

Vitamin B12 deficiency can manifest in various ways, including neurological disorders, macrocytic anaemia and, less commonly, pancytopenia with haemolysis. B12 deficiency can cause ineffective erythropoiesis, leading to intramedullary haemolysis and pancytopenia, which may mimic haematologic malignancies (Gilsing et al, 2010). Early recognition is crucial because prompt treatment with vitamin B12 leads to rapid recovery, while delayed diagnosis can result in irreversible damage, particularly in neurological functions (Langan and Goodbred, 2017). In this article, the authors present a case of severe vitamin B12 deficiency leading to pancytopenia and haemolysis in a patient with dietary restrictions in Uganda. They also discuss literature on the topic to emphasise the importance of awareness and timely intervention in this context.

Case study

A 66-year-old man from a rural area in western Uganda, with no family history of consanguinity, presented to the clinic with severe fatigue, breathlessness and frequent leg cramps over the past month. The man's carer also observed a yellowish discolouration of his eyes (scleral icterus) over the past year, which had intensified recently.

The man had been following a strict diet for the last 5 years, and consumed fruit and vegetables only rarely. His diet primarily consisted of processed grains and legumes, with little variety in food choices. Approximately 10 days before presentation, he had experienced an upper respiratory tract infection, which had resolved spontaneously without fever or other complications. On physical examination, the man appeared visibly pale and weak, with pronounced scleral icterus. His heart rate was recorded at 92 bpm, and a 2/6 systolic murmur was heard during auscultation.

Investigations

Laboratory tests revealed severe macrocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 6.8 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume (MCV), 118 fL), leucopaenia (white cell count 2630/µL; neutrophil count 1180/µL) and thrombocytopenia (platelets 112 000/mm3) (Table 1).

| Investigation | Before treatment | After treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 6.8 g/dL | 15.6 g/dL |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 118 fL | 88.2 fL |

| White cell count | 2630/µL | 6720/µL |

| Neutrophil count | 1180/µL | Normal (not specified) |

| Platelets | 112 000/mm3 | 252 000/mm3 |

| Reticulocyte count | 0.70% | Normal (not specified) |

| Serum indirect bilirubin | 3.8 mg/dL | 0.4 mg/dL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 5480 U/L | 170 U/L |

| Iron levels | Slightly reduced | 71 µg/dL |

| Vitamin B12 | 61 pg/mL | 325 ng/mL |

| Plasma homocysteine | >48 µmol/L | 8.1 µmol/L |

| Peripheral blood smear | Anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, hypersegmented neutrophils | Improved (not specified) |

| Abdominal ultrasound | Mild splenomegaly (Spleen length: 132 mm) | No mention of splenomegaly |

| Bone marrow aspiration | Megaloblastic erythropoiesis, no evidence of leukaemia | No mention of abnormal findings |

Reticulocyte count was notably low at 0.7%. Serum indirect bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and uric acid levels were elevated at 3.8 mg/dL, 5480 U/L and 8.7 mg/dL, respectively. Coombs test and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency testing were negative. Serum vitamin B12 was critically low at 61 pg/mL, while folic acid and iron levels were slightly reduced. The plasma homocysteine level was markedly elevated (>48 µmol/L). Serological testing for Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus indicated past infections. Screening for coeliac disease and pernicious anaemia yielded negative results.

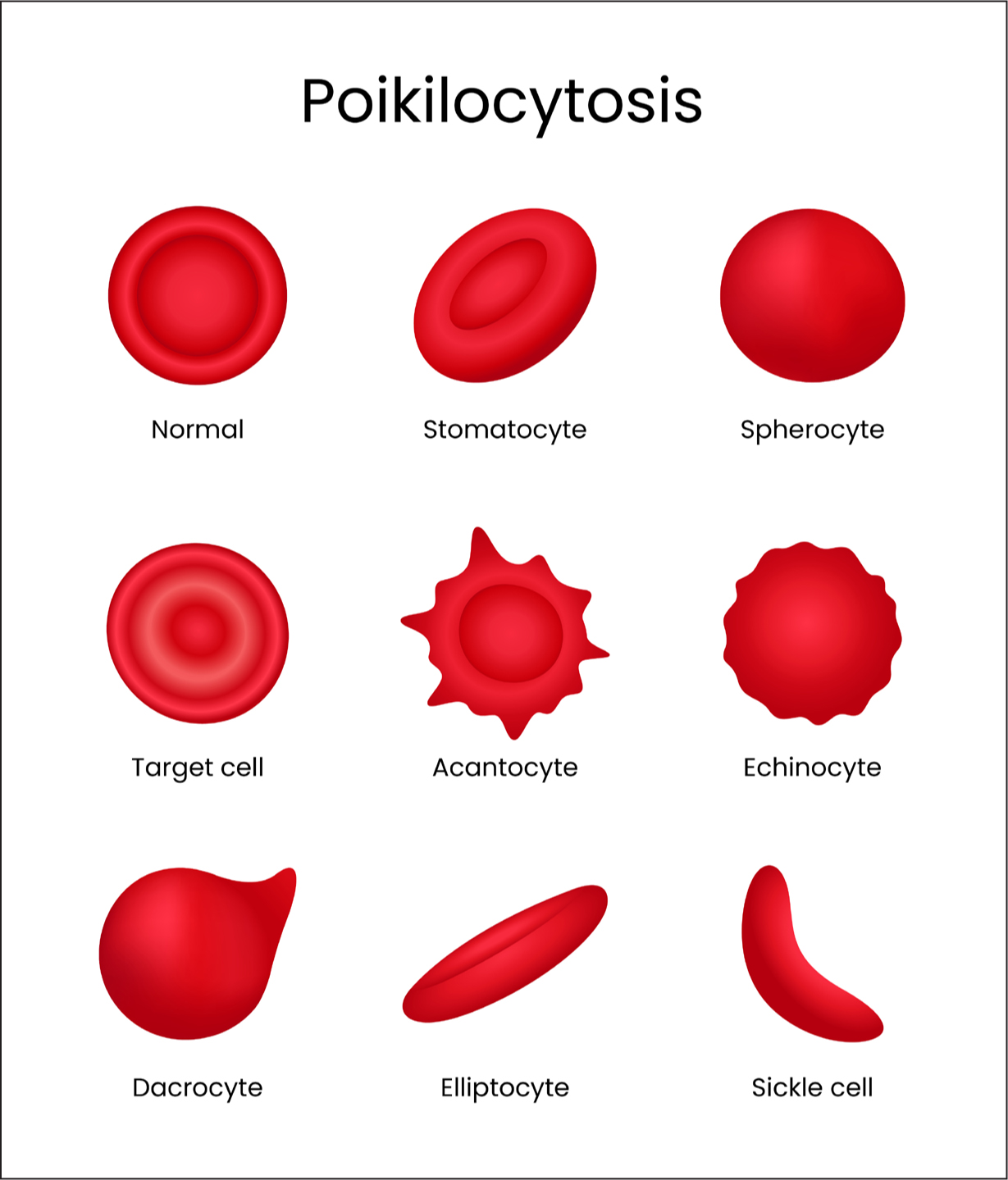

A peripheral blood smear showed significant anisocytosis, poikilocytosis (Figure 1) and hypersegmented neutrophils. An abdominal ultrasound revealed mild splenomegaly with a vertical spleen length of 132 mm. Bone marrow aspiration confirmed megaloblastic erythropoiesis without evidence of leukaemia.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included haemolytic anaemia, aplastic anaemia, infectious causes, and vitamin B12 deficiency. The laboratory findings of macrocytic anaemia, pancytopenia and haemolysis indicated severe vitamin B12 deficiency as the underlying cause.

Treatment

The patient was not transfused because of the absence of heart failure symptoms. He was started on intramuscular cyanocobalamin (1000 µg/day for 7 days, followed by weekly injections for 1 month, and then monthly for 6 months). Oral iron supplementation (ferrous sulfate 5 mg/kg/day) and folic acid (5 mg/day) were initiated in the second week of treatment because of his low iron levels and borderline folic acid levels.

Outcome and follow-up

Within a few days of initiating therapy, the patient reported increased energy and improved appetite. Five days into treatment, his haemoglobin increased to 6.4 g/dL and his white blood cell and platelet counts began to normalise. By the end of the second week, his pancytopenia and indirect hyperbilirubinemia had resolved.

At 2-month follow-up, he had gained significant weight and his laboratory results were within normal limits (haemoglobin 15.6 g/dL; MCV 88.2 fL; leukocyte count 6720/µL; platelets 252 000/mm3; serum indirect bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL; LDH 170 U/L; iron 71 µg/dL; ferritin 664 ng/mL; vitamin B12 325 ng/mL; plasma homocysteine 8.1 µmol/L).

Discussion

The association of Vitamin B12 deficiency with pancytopenia and haemolysis is not well-recognised (Remacha et al, 2011). The primary mechanism involves ineffective erythropoiesis and intramedullary haemolysis, which may cause elevated LDH and bilirubin levels, as observed in this case (Andres and Serraj, 2012). Dietary habits are a significant risk factor for B12 deficiency, particularly in vegetarians and vegans, as B12 is primarily found in animal products (O'Leary and Samman, 2010).

Literature highlights the growing prevalence of B12 deficiency among older individuals, especially those adhering to restrictive diets (Solomon, 2005). Awareness among healthcare providers is critical to prevent irreversible complications such as neurological damage and to improve outcomes through early treatment (Fernandes et al, 2024) This case study underscores the importance of considering vitamin B12 deficiency in the differential diagnosis of pancytopenia and haemolysis, even in the absence of overt neurological symptoms (Gladstone, 2019).

Management of severe B12 deficiency involves high-dose parenteral B12 replacement, which leads to rapid haematologic recovery (Pelling et al, 2022). The person in this case study responded well to treatment, which is consistent with findings in the literature (Pelling et al, 2022). Given the rising prevalence of vegetarian and vegan diets, particularly among older populations, this case underscores the critical need for proper dietary counselling.

Healthcare providers should be prepared to offer guidance on maintaining adequate B12 intake for patients following plant-based diets. This may include:

By implementing these strategies, healthcare providers can help prevent severe B12 deficiency cases such as the one presented here, while supporting patients in maintaining their chosen dietary patterns.

Limitations

While this case report provides valuable insights into severe vitamin B12 deficiency presentation in older populations, it has several limitations. As a single case study, the findings may not be generalisable to all patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. The patient's specific genetic factors, which might have contributed to the severity of the deficiency, were not explored.

Additionally, long-term follow-up data beyond 2 months, that could have provided information on sustained recovery and potential long-term effects of vitamin B12 deficiency, were not available.

Conclusions

This case of severe vitamin B12 deficiency in a 66-year-old vegetarian man underscores the importance of recognising vitamin B12 deficiency as a reversible cause of pancytopenia and haemolysis, even in older populations. Healthcare providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for vitamin B12 deficiency when encountering unexplained cytopenia, regardless of a patient's age.

Obtaining thorough dietary histories, especially in people with restrictive diets, is crucial for timely diagnosis. Initiating vitamin B12 supplementation promptly once deficiency is identified can lead to rapid clinical improvement. Furthermore, proactive nutritional counselling for at-risk populations, particularly older people adopting vegetarian or vegan diets, is essential for prevention. Community nursing plays a critical role in raising awareness, providing nutritional counselling and ensuring adherence to treatment, thereby improving outcomes and preventing long-term complications.