Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a contemporary health care concern that remains of global and national significance (Stolz et al, 2022). The UK population is living longer, with multiple comorbidities and long-term conditions, and a shift is needed to sustain the NHS service ethos of patient-centred care (NHS England, 2019). The specialist community practitioner district nurse (SCPDN) is clinically dedicated to lead and manage the care provision of those with complex long-term conditions within the community and in the home environment (The Queens Nursing Institute (QNI), 2016). They are well placed to identify and support individuals with COPD and contribute towards healthier communities for a more sustainable NHS. This article aims to critically analyse aspects of COPD relating to individuals, focusing on prevalence, screening, optimisation and the contribution of the SCPDN and the district nursing teams in these processes.

Impact and prevalence

COPD is a highly prevalent disease reported as the third leading cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). It is within the top ten global burden of diseases for those aged 50–75 years and over–75-years (Vos et al, 2020). The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (2021) define COPD as:

‘a common preventable and treatable disease…characterised by airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles or gases.’

Chronic inflammatory processes in the airways cause destruction of the alveoli and adjoining vasculature, resulting in debilitating symptoms (Lowe et al, 2019). The disease trajectory is variable with some individuals experiencing years of stability, followed by periods of acute exacerbations to end-stage respiratory failure (Lowe et al, 2019). GOLD (2022) recognises that comorbidities and exacerbations can contribute to the severity of the disease in individuals in the long term. Madawala et al (2023) identified the experiences of individuals in community settings with COPD often fell short of what they expected. They advocated strategies to improve experiences of care in the community such as improvements in self-management, quality of life, addressing expectations of health outcomes and preventing stigmatisation.

Prevalence data is troublesome in its reporting, with statistics heralded as ambiguous due to the cross over with other diseases such as asthma and late diagnosis (Hosseini et al, 2019). Clinical features often present later in the disease process, and even smokers are occasionally asymptomatic (Mehta et al, 2016; Rothnie et al, 2022). The latest estimation figures report 1 million people were diagnosed with COPD in England, with 2 million people thought to be undiagnosed (The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2019). About 52% of those with COPD are prevented from working as a result of the disease and hospitalisation (Foo et al, 2016) and the average admission rate across England and Wales for COPD have increased to 3.9% a year (Alwafi et al, 2023). This demonstrates the cost to the NHS, patients, families and communities as a consequence of COPD.

The district nursing service cares for individuals with complex needs and is important in the future health of our population, (McCrory, 2019). By 2035, 17% of over 65-year-olds in England are estimated to be living with four diseases or more (Kingston et al, 2018). Initial assessments of housebound patients on district nursing caseloads take a broad approach to assessment, informed by the nursing process; the new SCPDN standards specify an individualised holistic assessment, to ensure a patient-centred, evidence-based plan (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2022; Toney-Butler and Thayer, 2022). The role of the SCPDN in COPD is to support the home management of patients, although the QNI (2021) identified that extra support and training is required, particularly around diagnosis, assessment and management of exacerbations. Advanced clinical assessment and diagnostic skills which align to the advanced pillars of practice (Health Education England (HEE), 2017), are part of the SCPDN role and vital to support COPD patients with this unpredictable condition (NMC, 2022). The symptoms of COPD within the GOLD (2021) guidance determine shortness of breath, a chronic cough and sputum as indications of COPD, along with other risk factors such as tobacco smoking, pollution, occupational exposure, female gender and living in poverty. SCPDNs can educate their teams on risk factors and symptoms of COPD as best practice in order to manage the care of housebound patients as per the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence's guidance (NICE, 2018).

Increasingly, SCPDNs and their teams are under pressure to prevent avoidable emergency hospital admissions or readmissions for patients on their caseloads who may have been discharged and recovering from a COPD exacerbation (Lee at al, 2017). Symptoms characteristic of COPD exacerbations can include dyspnoea, worsening exercise tolerance, wheezing, increased sputum production, all of which can lead to hospital admissions and reduced quality of life (Miravitlles and Ribera, 2017; NICE, 2018). District nurses (DNs) can be proactive by looking out for fluctuations in these symptoms and alert the general practitioner (GP), community matrons and specialist respiratory services, should they consider extra support is needed for individuals to manage their disease.

DNs can look to optimising treatments for COPD using targeted approaches and individualised treatment plans as best practice (Sarwar et al, 2021). Optimisation does not merely refer to the control of symptoms, but rather, preventing and reducing exacerbations to maintain quality of life and slow disease progression. Best practice for the optimisation of those with COPD encompasses smoking cessation, vaccinations, personalised self-management plans, comorbidity optimisation and pulmonary rehabilitation to improve their health outcomes and quality of life (Foo et al, 2016; NICE, 2018).

Risk factors

Tobacco smoking is still considered the most prevalent cause of COPD, while occupational exposure is associated with its development, and may contribute to greater disease severity (Kraïm-Leleu et al, 2016; Onishi, 2017). Other risk factors have been identified in the diagnosis of the disease which include age, indoor and outdoor air pollution, poor growth in early life, childhood asthma and a rare genetic condition called alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, causing COPD at an early age (Ho et al, 2019; WHO, 2023). Diseases such as asthma, heart failure, bronchiectasis and previously treated illnesses such as tuberculosis or even human immunodeficiency viruses can co-exist with COPD and may account for under diagnosis of the disease and complicate symptoms (Ho et al, 2019). Over 80% of patients with COPD are estimated to have at least one chronic condition, and multimorbidity along with some comorbidities have a robust correlation with patient-related outcomes and mortality (Drummond et al, 2015; Yin at al, 2017).

In addition, the association between frailty, COPD and poor prognosis is discussed in recent studies citing frailty as the main factor determining its management and optimisation (Marengoni et al, 2018; Hanlon et al 2022; Zhang et al, 2022). Older people with COPD have two-fold increased probability of frailty (Marengoni et al, 2018). Frailty increases the risk of mortality, falls, adverse drug reactions and hospital admissions (Hoogendijk et al, 2019). DN teams have exposure to individuals living with COPD and frailty who are more vulnerable to decompensation and adverse health outcomes (Hanlon et al, 2022); yet, this is not recognised in COPD diagnostic guidelines (NICE, 2018; GOLD, 2021). NHS England (2017) have suggested frailty is fundamental in care planning for 65-year-olds and over, advocating the use of a frailty tool; therefore, familiarisation of frailty assessments for the SCPDN and DN teams is essential to ensure holistic care. Best practice to reduce the risk associated with frailty can include use of the comprehensive geriatric assessment approach supported by a toolkit for use within primary care (British Geriatrics Society, 2019). It advocates a multidimensional holistic assessment of older people to consider their health and wellbeing, and is crucial to the management strategy in suspected frailty to improve health outcomes.

Socio-economic influences, environmental and social circumstances which impact upon the health of communities must also be understood as risk factors. SCPDNs work collaboratively with patients and families to improve health, wellbeing and self-management (Gray, 2020; NMC, 2022). The Public Health Institute (2021) have highlighted deprived areas in England, noting higher levels of COPD diagnosed in the North (Public Health Institute, 2021). Care planning must take into consideration that those living in deprivation are more likely to have experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and adverse health outcomes (Hughes et al, 2017). Hardcastle et al (2020) have linked ACE exposure to smoking and diagnosed COPD. Healthcare professionals must understand ACE and have trauma-informed education to support patient empowerment.

The current cost-of-living crisis faced by the UK population may also perpetuate the cycle of deprivation linked to higher health risk behaviours such as smoking (Pleasants et al, 2016; Royal College of Physicians, 2022). Understanding local populations is paramount to ensure DN services meet the needs of patients (NMC, 2022). Challenges with variations in demographics and high disease prevalence mean DNs must develop an awareness of how best to advocate and apply evidence-based practice to those in deprived areas (Marmot et al, 2010; NMC, 2022). Social circumstances which are of particular concern are: unemployment or low income, low levels of education, residential segregation, stress, the physical environment, fragility and accessibility to health services (Pleasants et al, 2016). To identify areas of concern the SCPDN can contribute by continuous caseload profiling, auditing and evaluating care by communicating with DN team members and safety huddles to highlight those at risk (Harper-McDonald, 2020; Gray, 2020). This can support patients by promoting inclusivity and equality, and to influence service improvements within communities they work in (QNI, 2016; NMC, 2022).

Diagnosis

Spirometry is the gold standard for diagnosis of COPD, along with presenting symptoms (GOLD, 2021; NICE, 2021) and NICE (2018) suggest healthcare professionals must have access to spirometry and adequate training. Recent studies highlight concerns with overuse and misinterpretation of spirometry leading to misdiagnosis (Gershon et al, 2016; O'Sullivan et al, 2018; Stolz et al, 2022). The right care pathway for COPD suggests education of healthcare staff for spirometry testing (NHS England, 2017). SCPDNs are well-placed to contribute towards identifying housebound patients who may have COPD by concise history-taking and identification of symptoms. This offers an opportunity to use their skills in the quest to find ‘the missing millions’ in areas with below average COPD prevalence (NHS England, 2020).

Genomic screening is a contemporary option in supporting diagnosis for some individuals. Genomics is a term to describe the study of a person's entire genes, also known as the genome. It includes the interactions of the genes with each other and a person's environment (Puddester et al, 2022). It provides underpinning knowledge to understand individuals' health risks for conditions, the manifestation of diseases, and therapeutic responses to interventions or new therapies, (Calzone et al, 2018). An example of genetic influence can be seen in COPD with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, which is a genetic condition characterised by low levels of the main protease inhibitor in human serum (Soriano et al, 2018; Silverman, 2020).

Screening for this deficiency is a quick and effective blood test which can lead to earlier detection, management and smoking cessation interventions to optimise lung function in this high-risk group (da Costa et al, 2019). However, this is not a conventional diagnostic pathway for those with COPD. Only those that present with COPD early in life, who rarely smoked or had familial history are tested in this way (NICE, 2018). Earlier detection and optimisation of patients contributes to fewer hospitalisation, and it is imperative that the SCPDN is fully educated on the impact that screening can have for the COPD patient along with long-term management (Mehta et al, 2016; NMC, 2022). Holistic district nursing assessments, paying close attention to ongoing respiratory symptoms, age and family history may help to identify individuals who would benefit from genomic screening. SCPDNs must raise awareness within their teams to highlight rapid changes in genomic technology because genomic literacy among healthcare professionals remains low (Calzone et al, 2018). Patients with COPD may require the involvement of DNs with regards to symptom control or psychosocial therapeutic support due to genetic components, rather than being responsible for diagnosing or assessing people's risk of disease (Saleh et al, 2019).

When diagnosing and treating individuals who are exacerbating, SCPDNs need to consider antibiotic stewardship and antimicrobial resistance. Evidence suggests at least 50% of exacerbations involve bacteria which would benefit from antibiotic therapy, indicating many exacerbations are unrelated to bacterial infections (Jacobs et al, 2019; Sherrell, 2021). Stolbrink et al's (2019) large retrospective study analysed antibiotics prescriptions for individuals with COPD experiencing non-pneumonic exacerbations. Their study supported amoxicillin as the index drug of choice and noted that a shorter duration of antibiotic prescribing was not associated with repeat prescriptions. McCloskey et al (2023) identified a link between increased antibiotic prescribing and areas of poverty, with the North East and North West of England having increased prescribing rates for antibiotics and inhaled corticosteroid treatment. Clinicians who independently prescribe can access English Prescribing data to review local public health data to inform them of patterns of antibiotic prescribing and local guidelines for treating exacerbations. An example of this is the Pan Mersey Area Prescribing Committee Guidance (NHS Business Services Authority, 2023; Pan Mersey APC, 2023).

Patients on DN caseloads have multiple comorbidities and often access the multi-disciplinary team, resulting in antimicrobial treatment commenced by other clinicians (Sherrell, 2021, NICE, 2018). Medication reconciliation is important; by including a history of previous and current antibiotic therapy, it can enable SCPDNs to identify individuals having successive courses of antibiotic treatment which may lead to resistance (Stolbrink et al, 2018). COPD exacerbations can manifest in harm to patients, as well as the healthcare system as a consequence of recurrent antibiotic therapy (MacLeod et al, 2021). The risk to the patient is subtherapeutic treatment, recurrent infections requiring repeated treatment and antibiotic-resistant bloodstream infections, which are linked to high morbidity and mortality (Leal et al, 2019). SCPDNs should educate both patients and the district nursing team about the risks associated with antibiotic therapy. Recommendations are to encourage health promotion, which is proven to contribute to reductions in exacerbations and high antibiotic prescription rates (Rockenschaub et al, 2020; WHO, 2022). Health promotion can include pharmacological management, environmental factors, and patient activation measures to individualise care planning for these individuals.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a programme of education and exercise designed for people with lung disease such as COPD and those who experience symptoms of breathlessness (NHS England, 2019). It is found to relieve fatigue, improve emotional function and enhance patient control over the disease. Patients who complete a pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) programme report higher activity and exercise levels, as well as better quality of life (McCarthy et al, 2015; NHS England, 2019; Osadnik and Singh, 2019). It is considered a key intervention for those with COPD; however, it remains accessible to those only with breathlessness (NHS England, 2019; GOLD, 2021). Recent evidence reports a lack of referrals in primary care for PR, highlighting that female smokers and those from deprived areas are less likely to be referred (Stone et al, 2020). Patient experiences accessing services is often negative, with patients describing a struggle for referrals (Buttery et al, 2017; Casaburi, 2018). SCPDNs can support information-giving to champion PR and escalate delayed referrals by communicating with PR teams. PR is recognised by Quality Outcome Frameworks to avoid significant admissions and exacerbations over 10 years (NHS England, 2019; NICE, 2021).

Prevention

Those who stop smoking have fewer lower respiratory tract infections and COPD exacerbations, and the longer COPD patients have quit smoking, the healthier they will be (Au et al, 2009’ Li et al, 2022). The WHO (2003) tobacco control framework implemented the highest taxation on tobacco products in Europe (Branston et al, 2021). Yet, the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022) reported England would miss the target to make itself smokefree by 2030 in 7 years, with those in poorer areas predicted to meet it in 2044. Accelerated action is needed to reduce smoking in England, encouraging smoker advice and support at every interaction. NHS Digital (2022) report that between April and December 2021, 54.5% of people who used NHS Stop Smoking Service either via group therapy or one-on-one support had quit, with more success coming from over 60-year-olds. Therefore, district nursing teams should advocate these services. Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) is also recognised to support quitting smoking along with counselling (Rigotti et al, 2012). SCPDNs with non-medical prescribing can prescribe within their scope of practice, initiating a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy when in contact with patient discussion (The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2019). SCPDNs without prescribing can still identify a patient's need for other treatment by communicating this to a GP or non-medical prescriber for further assessment, to guarantee parity in care (Maybin et al, 2016).

The importance of vaccinations beyond the pandemic also remains high on the UK agenda. NICE (2018) guidelines suggest pneumococcal, and influenza (flu) vaccination are offered for all COPD patients and the COVID 19 vaccine is also hailed as offering significant protection, (Gerayeli et al, 2021). High flu vaccination rates of over 65-year-olds were reported (82.3%) between 2021–2022, superseding the WHO vaccine uptake level in the same group of 75% (UK Health Security Agency, 2022). Information must be inclusive of advice that echoes the efficacy of vaccinations for flu and COVID-19 for those with a diagnosis of COPD (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, 2022). Vaccine rates are lower in deprived areas and in those of ethnic minority; therefore, the SCPDN must maximise opportunities for those on the caseload by promoting and educating the benefits, hence, ‘making every contact count’ (MECC) (Public Health England (PHE), 2016; Tan et al, 2021; While, 2021; Watkinson et al, 2022). High rates of uptake are inextricably linked to the COVID-19 vaccination booster programme, which demonstrates the benefit of education on immunisations and their role in maintaining health (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021). If SCPDNs can advocate the relevant vaccinations to this patient group, it may help reduce unplanned admissions in those with COPD moving forward.

PHE (2016) stated a MECC behaviour change model, can contribute to preventative measures. MECC (PHE, 2016) is an evidence-based method to encourage healthcare professionals to improve people's health and wellbeing by facilitating behavioural change. It aims to encourage and improve an individual's health and wellbeing through the dissemination of reliable information. MECC recognises that practitioners such as SCPDNs are well-placed to engage in conversations to address a number of risk factors for health such as smoking, alcohol and mental wellbeing and must take the opportunity to do so in practice. The intensity of the level of interaction for behavioural change cannot be ignored, with differing techniques needed (HEE, 2022), and NHS policies must reflect this resource and support training for staff on behaviour change (PHE, 2016). SCPDNs could benefit from specialised training and could facilitate implementation for wider DN teams if the model is developed further.

Workforce challenges

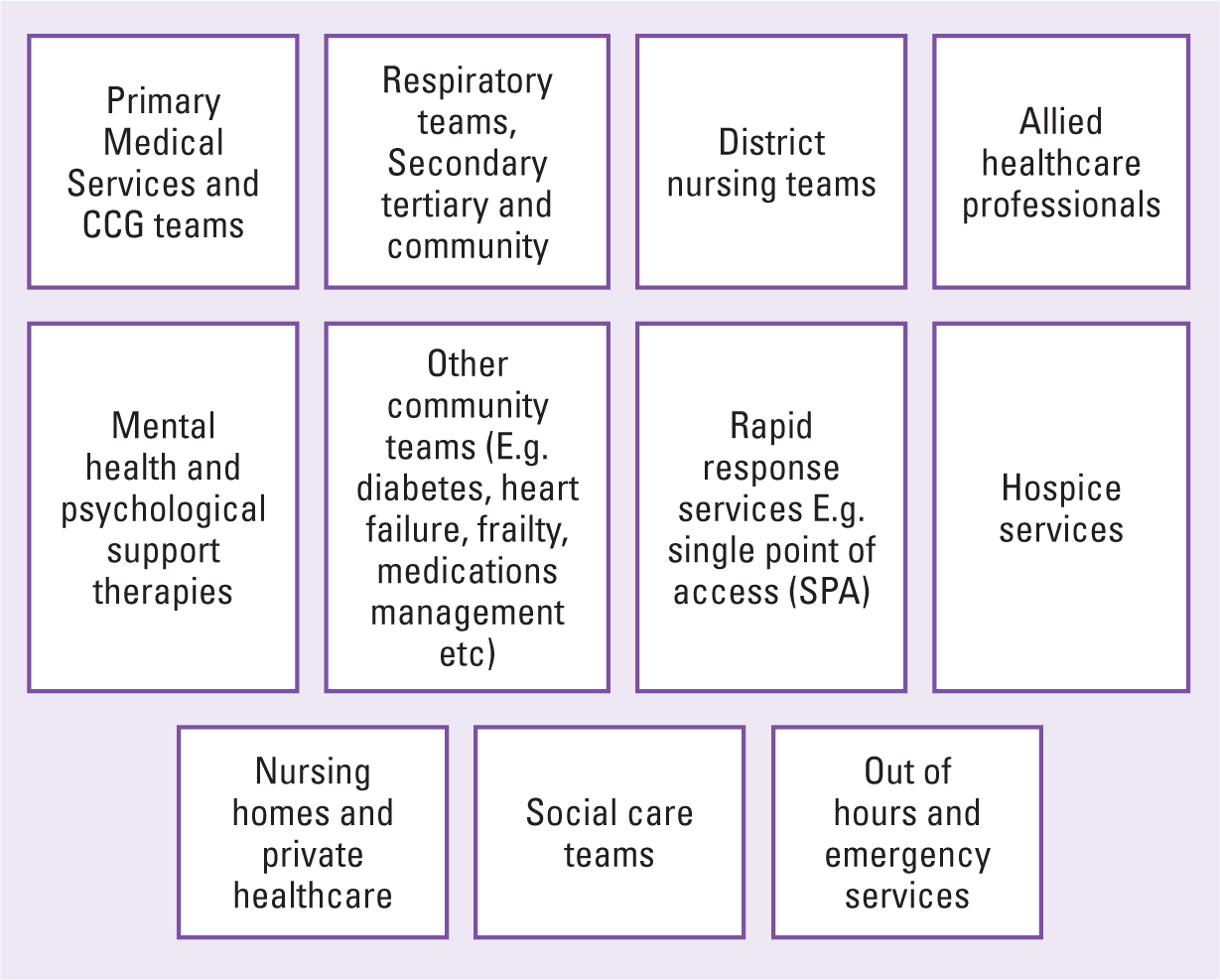

NHS England's (2020) recommendation for a whole system integrated approach advocating interdependencies between services is regarded as best practice, to ensure a place-base service for those with COPD. The strength of SCPDNs and district nursing teams may not lie in performing diagnostic testing, but rather, in the detection of COPD symptoms and the ability to provide personalised care, ensuring collaborative working relationships across primary and community care teams (NICE, 2018; QNI, 2019). Key teams and services involved in the care of those with COPD are in Figure 1, although this list is not exhaustive and also incorporates financial, contractual, business intelligence services and neighbouring CCGs and communities (NHS England, 2020). Collaboration with other teams is necessary to inform the SCPDN about associated local services and understand criteria to access and discharge patients with COPD (Chew and Mahadeva, 2018).

NHS England's (2022) priorities are to make the NHS a better place to work and empower staff to deliver outstanding, high-quality care. Evidence acknowledges that DN services provide valuable contributions towards the assessment, management and optimisation of COPD patients, although demand for the service must be determined. The assessment for risk and demand of district nursing teams fall within the responsibility of the SCPDN and the recent staffing crisis cannot be ignored (NMC, 2022). Maybin et al (2016) have highlighted the lack of data analysed for community health services in contrast to hospital data, which is extensively collated to predict workforce pressures; yet, little data exists to quantify demands in community services (NHS Digital, 2022). The Workforce Standards for District Nurses (QNI, 2022) recognised that DN services remain a service to fill the gap of more specialised services unable to meet the demands of their patients. The SCPDN has a responsibility to lead, advocate for staff and escalate to commissioning bodies, when challenged with patients who fall out with the criteria of district nursing services. This aims to protect and safeguard staff wellbeing and patients alike (QNI, 2022). Compassionate leadership skills prioritise staff support and development, and are thought to provide opportunities to enhance the care of patient groups (Bailey and West, 2022).

Conclusion

COPD is determined as a health care priority and the SCPDN is well-placed to contribute to the diagnosis, management and optimisation of the disease. Globally, COPD is a leading cause of hospitalisation and death. It is underdiagnosed and there are challenges in prevention, screening and managing COPD in the long term. The UK population is predicted to live longer with more co-morbidities; therefore, it is fundamental that SCPDNs and district nursing teams holistically assess individuals to provide quality, patient-centred care.

Opportunities to improve management are prevalent pertaining to frailty assessment, nutritional input, genomic testing and spirometry. Strategies such as pulmonary rehabilitation, integrating healthcare systems, holistic assessments and health promotional approaches are endorsed. Current guidance provides the latest evidence that district nursing services have the skills to support COPD populations further. However, there must be recognition of poor accessibility to current services and a shortfall in the DN workforce before teams can provide sustainable patient-centred care for those with COPD.

Key points

- District nursing teams deliver long term care to individuals with chronic complex conditions

- The chronic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) embodies health promotion, prevention, and optimisation

- Social determinants of health can adversely affect outcomes in care for patient with COPD

- Workforce challenges and accessibility are barriers for district nurses when providing care to the COPD population.

CPD reflective questions

- Consider health needs assessments in planning care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Reflect on opportunities for district nursing teams to optimise the care of individuals with COPD

- Identify evidence-based strategies highlighted in the article in the promotion of COPD patients locally.