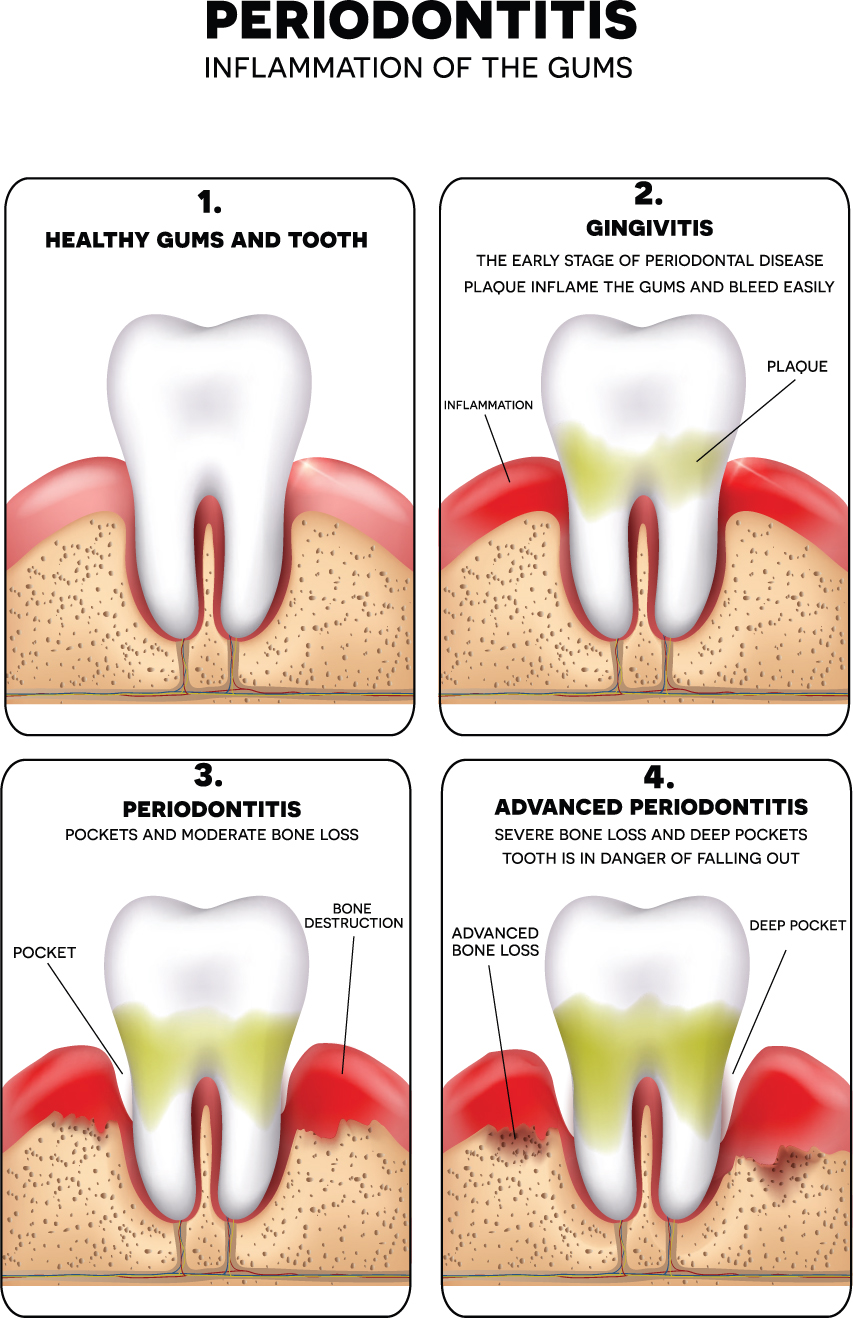

Periodontitis, commonly known as gum disease, refers to inflammation of the periodontal tissue surrounding the teeth. Pathogenic bacterial infiltration of the gum tissue causes an immune-mediated inflammatory response that results in destruction of the connective tissues and bone that support the teeth (Figure 1). Periodontal disease can be classified as chronic or aggressive and localised or generalised, depending on the presentation of the disease and its progression over time, respectively. If left untreated, it can lead to overt inflammation and progressive mobility of affected teeth as the gap between the tooth and the gum increases. This can result in pain, difficulty eating, aesthetic concerns and tooth loss (Manresa et al, 2018). According to estimates from the World Health Organization, between 1% and 79% of the global population suffers from advanced periodontal disease (WHO, 2004).

Treatment of active periodontitis begins with reducing or eliminating the pathogenic microbial load. This involves a combination of self-care by patients in performing regular oral hygiene and interventions by dentists. The latter includes mechanical debridement of any plaque or calculus deposits, the use of antimicrobials and surgical interventions to facilitate access for debridement by dentists (Manresa et al, 2018). As part of their role dentists need to provide education to ensure that these patients are able to perform oral hygiene effectively.

Patients with a history of periodontitis are at a high risk of future episodes and are thus often closely monitored via a formal programme of supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). According to the American Academy of Periodontology, SPT should include all components of a typical dental recall examination, as well as periodontal re-evaluation and risk assessment, supragingival and subgingival removal of bacterial plaque and calculus and re-treatment of any sites where recurrent or persistent disease is present (American Academy of Periodontology, 1998). Any persistent periodontal pockets are debrided to prevent bacterial colonisation and thereby minimise the inflammatory response that underpins disease progression. In this way, dentists can promote periodontal health and detect and respond to any recurrence or progression of periodontal disease (Manresa et al, 2018). The success of SPT regimens has been demonstrated in a number of long-term retrospective studies, but there is a lack of consensus about the best approach to use during SPT and the optimal means for delivering it (Manresa et al, 2018).

Objective

The review described in this article (Manresa et al, 2018) aimed to determine the effects of supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) in the maintenance of the dentition of adults treated for periodontitis.

Intervention

The review included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with at least 12 months' follow-up. Follow-up was defined as the period of SPT in which the interventions were compared. Participants included adults aged 18 years and older who had previously been treated for moderate to severe chronic periodontitis. The following interventions were compared:

The outcome measures were evaluated for results reported at 12 months or the nearest point in time. The primary outcome measures considered in this review were as follows:

The secondary outcomes assessed included probing pocket depth; patient-reported outcome measures, for example, satisfaction with treatment; cost effectiveness of SPT compared to overall dental care with or without SPT; and cost effectiveness of SPT relative to the frequency of SPT.

Results

Only four studies relevant to the review objectives were identified. These included 307 participants aged between 31 and 85 years of age.

None of the included studies measured tooth loss; however, other outcome measures such as bleeding on probing, clinical attachment level and probing pocket depth, which represent signs of inflammation and potential periodontal disease progression, were considered. There was no evidence available that evaluated SPT versus monitoring only or SPT provided at different time intervals, and no studies compared different methods for mechanical debridement. There was a very limited amount of low-quality evidence to suggest that adjunctive antibiotics may not provide any additional benefit for SPT compared to mechanical debridement alone, and that it may not make a difference whether SPT is provided by a general dentist or specialist. Overall, the available RCT evidence was insufficient to draw any reliable conclusions about SPT.

Conclusions

The authors of the review concluded that the quality of evidence was low to very low, because of the limited number of studies, relatively small numbers of participants and high or unclear risk of bias in three of the four included RCTs. In addition, a number of limitations in the included studies were noted. Three of the studies were based in university dental hospitals or specialist clinics, and this limited the applicability of the evidence to patients in general practice, who may be less compliant with traditional SPT modalities and thus experience greater benefits from alternative or adjunctive treatments. In addition, longer follow-up periods may be needed for some of the outcome measures, for example, tooth loss. Implications for practice SPT is an important preventive strategy for patients with a history of periodontal disease, but the optimum evidence-based approach has yet to be determined. There is a lack of clear guidelines and protocols to guide the clinical application of adjunctive SPT at different time intervals. Dental professionals should continue to use existing techniques to monitor disease progression or recurrence and thus maintain dentition in affected individuals.