Traditionally, the lymphatic system has not received the attention it deserves, despite its critical biological and clinical significance (Borst et al, 2024; Greener, 2024). The lymphatic system includes a network of endothelial tubes (lymphatic capillaries), nodes and other organs, including the spleen and thymus (Borst et al, 2024; Panara et al, 2024). Nearly all tissues are supplied with capillary-like initial lymphatics, which drain into a network of collecting vessels before emptying into larger ducts (Borst et al, 2024; Karakousi et al, 2024; Petkova et al, 2024). However, the lymphatic system is more than a network of tubes (Greener, 2024). The lymphatic system maintains interstitial fluid levels and carries immune cells and antigens to lymph nodes (Borst et al, 2024; Karakousi et al, 2024; Petkova et al, 2024). Cells in lymph nodes contribute to immunity, release signals that control the growth and regeneration of several tissues, including the skin, and modulate metabolism (Karakousi et al, 2024; Pagliara et al, 2024). Chronic oedema (lymphoedema) arises when lymphatic drainage declines (National Lymphoedema Partnership (NLP), 2019).

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) can develop after a deep vein thrombosis and is responsible for up to 70.0% of all chronic leg ulcers (Poku et al, 2017; Mills and Armstrong, 2024). Established risk factors include age, gender, obesity, pregnancy, history of deep vein thrombosis and prolonged standing. Other risk factors associated with varicose veins include low bioimpedance and greater height (Fukaya and Kolluri, 2024).

Compression is the cornerstone of treatment for CVI and lymphoedema (Herberger et al, 2017; Rabe et al, 2018; NLP, 2019; Rockson et al, 2019; Mills and Armstrong, 2024). For instance, compression stockings halve the probability of the recurrence of venous leg ulcers (VLUs) (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). However, between 30.0% and 65.0% of patients do not fully adhere to any form of compression therapy (Mills and Armstrong, 2024).Therefore, the choice of compression wrap is important to optimise financial and clinical outcomes. This article introduces and dicusses Biflex Self Adjust, a new compression wrap system for lymphoedema and VLUs.

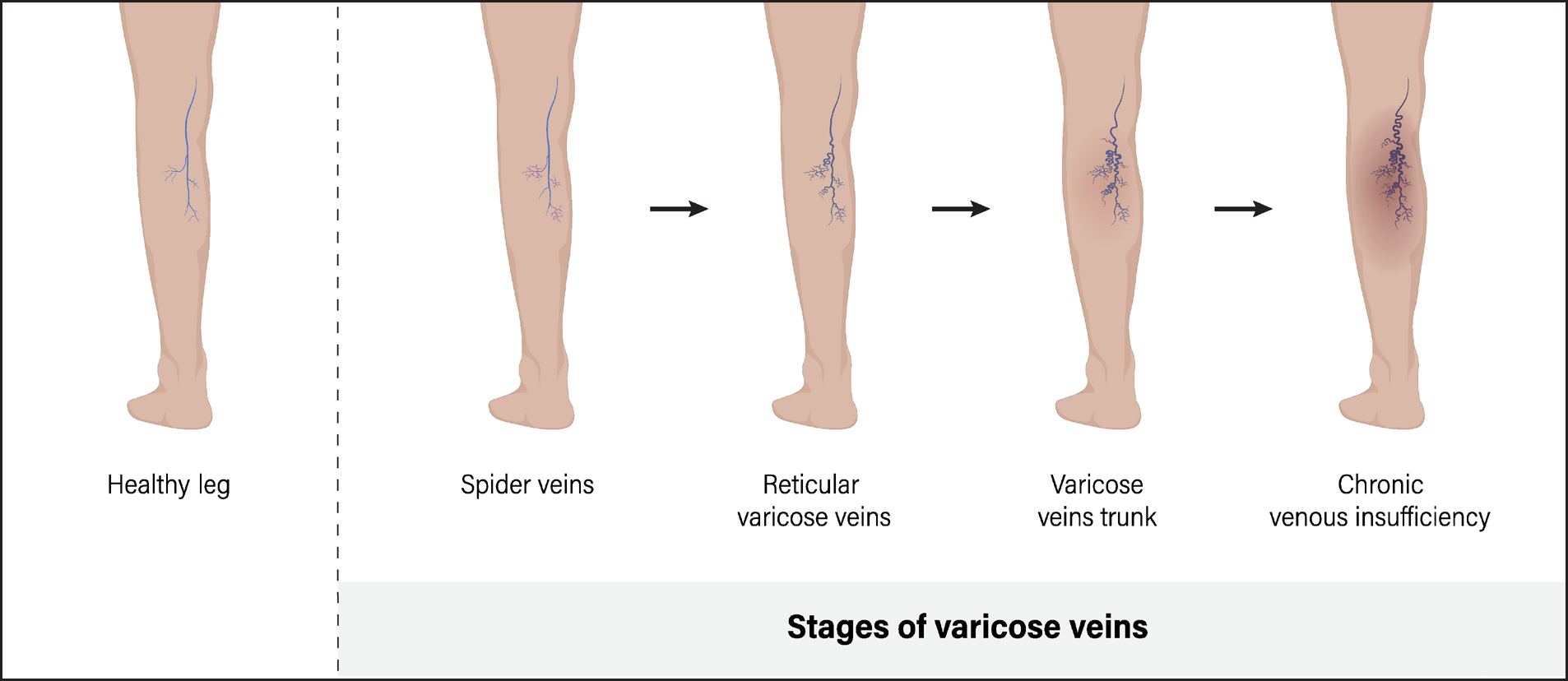

Chronic venous insufficiency

The return of blood from the legs depends on normal calf and foot muscle pump activity, open (patent) veins and functional venous valves. Problems with one or more of these functions can cause venous insufficiency (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). CVI usually refers to patients with changes such as oedema, abnormal skin pigments, ulcers and dilated tortuous (varicose) veins (Mills and Armstrong, 2024).

CVI symptoms arise from prolonged raised pressure in the veins in the legs, which causes venous stasis and ischaemia of local tissues (Figure 1) (Poku et al, 2017; Mills and Armstrong, 2024). In turn, the increased pressure usually reflects dysfunctional valve function following deep vein thrombosis and recanalisation through the clot (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). Nearly half of all deep vein thrombosis patients develop CVI within 5–10 years (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). Patients can also develop CVI from rare congenital absences of functional valves (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). Epidemiological estimates of CVI vary considerably, partly reflecting differences in diagnostic criteria (Mills and Armstrong 2024). Approximately 8.0% of the population experiences oedema, while 4.0% develops skin changes because of CVI (Salim et al, 2021). Additionally, around 1% of the population has healed VLUs and 0.1–0.4% has active VLUs (Poku et al, 2017; Salim et al, 2021).

Several symptoms suggest that a patient has CVI, rather than lymphoedema. Oedema caused by CVI can cause transient non-tender pitting oedema, as is common in lymphoedema (Grada and Phillips, 2017). Moreover, CVI patients usually show other symptoms of venous disease, such as varicose veins, brown to red skin pigmentation and VLUs (Grada and Phillips, 2017). A study of 150 CVI patients found that 82.7% had at least one skin issue including insufficiency dermatitis (32.7%), telangiectasia (25.3%) and changes in pigmentation (19.3%). Moreover, 48.7% and 32.7% of CVI patients reported itching and pain, respectively (Kılınç et al, 2022).

VLUs can take a considerable time to heal (10.0–20.0% are treated for more than a year) and can profoundly impact a person's quality of life (QoL) (Poku et al, 2017; Patton et al, 2024). The daily application of compression bandages and dressing changes once or twice a week, which is time-intensive, contributes to poor QoL in people with VLUs. Pain has an impact on many areas of daily life, including sleep and mobility. Not surprisingly, people with VLUs may become depressed (Patton et al, 2024). VLUs also create considerable costs for the NHS, between €245 and €287 million in primary care during 2005–2006 (Poku et al, 2017). Urwin et al (2022) estimated that the average 2-week cost of treating patients with a VLU as the most severe wound was £166 per person. The annual cost of treating VLU was £102 million for the UK and the per person cost was £4787.

Lymphoedema

Lymphoedema arises when a damaged or dysfunctional lymphatic system leads to the accumulation of extracellular fluid in tissues (Rockson et al, 2019). The affected part of the body shows progressive swelling and chronic tissue inflammation (Rockson et al, 2019). Lymphoedema can arise in any part of the body, including limbs, trunk, head and neck, breasts and genitals, and can be unilateral or bilateral (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016; Grada and Phillips, 2017; Klernäs et al, 2018).

Chronic oedema encompasses all forms of oedema that are present for at least three months, irrespective of the pathogenesis (Moffatt et al, 2017). However, lymphoedema is mainly primary or secondary. Primary lymphoedema typically arises because of mutations in genes responsible for the development of lymphatic vessels (Rockson et al, 2019). Secondary lymphoedema arises from damage to the lymphatic vasculature from trauma and non-trauma causes, such as obesity. For instance, a tumour, cancer surgery or radiotherapy can damage or remove parts of the lymphatic system (Klernäs et al, 2018; Rockson et al, 2019).

Cancer can cause secondary lymphoedema (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016). The risk depends on malignancy and procedure: about 6.0% of breast cancer patients develop lymphoedema following sentinel lymph node biopsy. The prevalence rises to 83.0% among melanoma patients who undergo inguinal lymph node dissection (Rockson et al, 2019). Regional lymph node radiation increases the risk of lymphoedema in breast cancer patients by 70.0%, compared with chest wall and/or breast radiotherapy (McEvoy and Feldman, 2024). A study from Derby found that malignancies and cancer treatment caused 3.0% of chronic oedema cases in the community (Moffatt et al, 2017). Lymphovenous dysfunction, infection, inflammation, trauma, immobility, dependency and obesity also cause or contribute to secondary lymphoedema (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016). In the Derby study, 69.5% of patients were obese or morbidly obese and 28.5% of hospital inpatients had chronic oedema (Moffatt et al, 2017).

The NLP (2019) suggests that between 263 000 and 422000 people have chronic oedema. Cooper and Bagnall (2016) estimated regional prevalences of 3.59:1000 and 2.29:1000 in the south west of England and West Midlands respectively. The prevalence of primary lymphoedema was one in every 2763 people in the south west of England and one in every 8006 of the population in West Midlands. The prevalence of secondary lymphoedema was one in every 304 and 457 people in the south west of England and West Midlands, respectively (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016).

Age and sex are important risk factors for chronic oedema. The Derby study estimated that the crude prevalence of chronic oedema was 3.93 per 1000 of the population. The prevalence was highest among people aged 85 years or above (28.75 per 1000) and higher among women (5.37 per 1000) than men (2.48 per 1000) (Moffatt et al, 2017). Women accounted for 84.0% and 77.0% of patients in the south west of England and West Midlands, respectively (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016).

Lymphoedema can significantly undermine many aspects of QoL (Figure 2) (Herberger et al, 2017; Klernäs et al, 2018). A study of 129 patients from Sweden reported that lymphoedema had a major impact on the QoL of 20% of participants (Klernäs et al, 2018). Breast-cancer related lymphoedema can cause depression, undermine QoL and result in loss of employment (Sharifi and Ahmad, 2024). Moreover, NHS England spends more than £178 million on lymphoedema admissions and £172–254 million on managing cellulitis every year (NLP, 2019).

Early-stage lymphoedema can mimic other causes of tissue swelling (Grada and Phillips, 2017). The differential diagnosis includes venous oedema, lipoedema (lipalgia), obesity and drug-induced swelling (Grada and Phillips, 2017). A total of 40% of chronic oedema patients in the Derby study had concurrent leg ulcers (Moffatt et al, 2017).

Patients with chronic lymphoedema have a higher protein content in tissue fluid than those with venous oedema. Therefore, chronic lymphoedema patients are particularly prone to recurrent skin infections (Grada and Phillips, 2017). Patients with chronic lymphoedema can develop skin fissures, ulceration, recurrent cellulitis, impetigo and lymphorrhoea (clear to light yellow lymph fluid oozing from the skin) (Grada and Phillips, 2017).

Dermatological changes are common in lymphoedema. People with newly developed lymphoedema typically show transient non-tender pitting oedema. This evolves into pitted, dimpled skin (peau d’orange) and then into a leathery texture caused by skin thickening and tissue fibrosis (Grada and Phillips, 2017). Non-pitting oedema indicates irreversible lymphoedema. Patients often show the Kaposi-Stemmer sign: the fold of skin at the base of the second toe cannot be pinched (Grada and Phillips 2017). Ultimately, chronic lymphoedema leads to a warty hyperkeratotic appearance called elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (Grada and Phillips, 2017).

Many patients report that the affected limb feels heavy and uncomfortable, especially towards the end of the day, and they have poorly controlled pain (Grada and Phillips 2017; Herberger et al 2017). Herberger et al (2017) assumed that a score of above 3 on a visual analogue scale (from 0 [no pain] to 10 [maximum pain]) represents at least moderate pain and requires treatment. Herberger et al (2017) reported that 45.1% of 358 lymphoedema patients experienced pain that required treatment, yet only 19.8% received analgesics. These findings suggest a substantial undertreatment of lymphoedema-related pain. Some studies suggest that compression wraps can alleviate pain and improve QoL when used correctly in CVI and chronic oedema patients (Rabe et al, 2018).

Compression wrap

Treatment of chronic oedema includes compression, exercise and, in some people, skin care such as using a moisturiser to reduce dry and flaky skin (Herberger et al, 2017; Mills and Armstrong, 2024). Treatment is continuous and often for the rest of the patient's life (Herberger et al, 2017; Mills and Armstrong, 2024). In breast cancer patients, exercise reduced lymphoedema severity in four of 13 randomised clinical trials (Lian et al, 2024). In particular, resistance exercise and yoga appeared to reduce lymphoedema severity (Lian et al, 2024). The review recommends daily, or almost daily, exercise at home. Patients may not maintain the improvement once exercise stops. Therefore the authors recommend that ‘exercise should be a lifelong practice’ (Lian et al, 2024).

In CVI patients, graded compression is the foundation of treatment and prevention of oedema, statis dermatitis and VLUs (Rabe et al 2018; Mills and Armstrong, 2024). A few patients may need surgery or another specialist treatment for CVI (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). However, between 30.0% and 65.0% of patients do not adhere fully to any kind of compression therapy (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). VLUs recur in up to 45.0% of patients (Poku et al, 2017). Adherence halves the likelihood that VLUs will recur (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). Compression can also improve skin changes in people with venous disease (Rabe et al, 2018).

Against this background, the remainder of this article focuses on Biflex Self Adjust compression wrap, marketed by Thuasne®. Founded in 1847, Thuasne® initially specialised in producing narrow elastic textiles. Today, Thuasne® is a European leader in medical devices for orthopaedics and compression, with an extensive range of products: Mobiderm®; Venoflex Micro and, most recently, Biflex Self Adjust compression wrap (Thuasne® personal communication). This innovative product reflects Thuasne's® ongoing commitment to advancing healthcare solutions that improve patient outcomes.

Building on this legacy, Biflex Self Adjust offers a user-friendly design tailored to improve patient adherence to compression therapy. Compression options currently available on the market include traditional multilayer bandages, layered compression hosiery kits and other compression wrap systems. Multilayer bandages are typically applied in multiple layers by a healthcare professional to exert graduated pressure, while compression hosiery kits offer the ability to modify pressure. Patients often require additional support for reapplication or adjustment.

Multilayer bandages generally rely on static compression. While they exert consistent levels of pressure once applied, the bandages do not easily accommodate changes in limb size throughout the day. As a result, healthcare professionals need to reapply bandaging periodically to ensure that the correct pressure is maintained. In comparison, Biflex Self Adjust provides a more dynamic solution. The design allows for easy pressure adjustments without the need for reapplication. This user-friendly feature allows for tailored, real-time adjustments, enhancing patient comfort and improving adherence to treatment. While Biflex Self Adjust shares the same general indications and compression goals as other available wraps, its unique integrated adjuster sets it apart by offering patients and healthcare professionals a more convenient and effective way to manage their compression levels (Thuasne®, personal communication).

Healthcare professionals should remind patients to put the compression wrap on first thing in the morning. Patients should remove the compression wrap when lying down, usually just before going to bed (Mills and Armstrong, 2024). A Velcro system and an integrated loop ensure that patients can easily and quickly take Biflex Self Adjust on and off. There is no need for the patient or healthcare professional to redo the bandage to reduce the pressure. Biflex Self Adjust can accommodate an increase of 5.0% or a decrease of 10.0% in limb circumference. The correct pressure is maintained for as long as the patient wears Biflex Self Adjust (Thuasne®, personal communication). Biflex Self Adjust uses a patented integrated device that allows patients to easily adjust the pressure. Thuasne® recommends a minimum pressure of 20–40 mmHg for lower limbs and 20–30mmHg for the arms. The adjuster allows three levels: low, medium and high pressure. The healthcare professional or patient pulls on a strap, which slides the adjuster to the desired pressure. Adjusting the loops from bottom to top allows the application of the optimal pressure to each limb segment (Thuasne®, personal communication).

Biflex Self Adjust completely covers the limb using an optimised number of overlapping bandages, which helps prevent oedema migration. Healthcare professionals and patients should ensure that no large folds are visible. The open-cell foam used in Biflex Self Adjust allows moisture transfer, which enhances comfort (Thuasne®, personal communication). The following case studies illustrate the effectiveness of the Biflex Self Adjust in naturalistic clinical practice.

Case studies

Case study one

The effectiveness of the Biflex Self Adjust in healing a left limb ulcer resulting from a traumatic injury

Joy Tickle, Tissue Viability Nurse Consultant

A 78-year-old patient presented with a left lower limb wound, resulting from a traumatic injury caused by a car door. The patient was under the care of the district nursing team. Her medical history included diverticulitis, asthma, atrial fibrillation, varicose veins and hemosiderin staining. Socially, the patient reported that the wound caused significant pain, with delayed healing contributing to heightened anxiety. She was experiencing repeated infections and requiring antibiotic treatments, which exacerbated her distress. The patient also had difficulty in mobilising because of pain and had become increasingly dependent on her husband and family for support. This dependency caused additional anxiety, as she felt she was losing her independence and her identity as a wife, mother and grandmother. Her hobbies, such as baking and spending time with her grandchildren, were significantly affected. She found it difficult to stand while baking and the pain and infections left her feeling unwell and tired, reducing the amount of time she could spend with her grandchildren. She shared with the team that she felt she was ‘letting her family down’. Her QoL was significantly impacted, with increasing frustration over the prolonged duration of the wound and its lack of improvement. The patient also expressed anxiety while waiting for the district nurse visits, as these were not always at the same time. She felt reluctant to invite friends or family to her home on these days owing to the embarrassment of the wound's malodour when infected, as well as the fear of leakage from the wound (Figure 3).

At the time of assessment, her QoL score (assessed using the Tickle 2020 QoL tool) was 50 (on a scale of 10–70, with 70 indicating the most significant impact on QoL), and her pain score was 8 (on a scale of 1–10, with 10 being the worst pain). Medications included Serello 25 mcg, Digoxin, Co-codamol and Buscopan 10mg each.

Previous treatments had included multiple antimicrobial primary dressings, including silver and honey-based dressings, as well as foam dressings. Despite these efforts, the wound had failed to reduce in size, measuring 30mm by 20mm. The wound bed consisted of 20.0% slough and 80.0% granulation tissue, with a risk of reduced healing and infection because of the patient's medication, venous disease and limb oedema. Exudate levels were low, serous in colour and had minimal viscosity. The peri-wound skin was fragile but intact.

Given the size of the wound, minimal exudate, venous disease and moderate oedema, it was agreed with the patient to apply compression therapy in the form of a wrap system. Wrap systems are effective for managing patients’ wounds that present with characteristics such as low exudation and minimal limb distortion, as seen in this patient.

The Biflex self-adjustment compression wrap was prescribed, and its use was explained to the patient and the community nursing team. The wrap system used coded indicators that allowed for the application of the correct mmHg pressure based on the patient's needs. The primary and secondary treatment regimen remained unchanged:

After 3 weeks of treatment, the wound had reduced considerably in size (10mmx10mm, compared to the baseline) with the wound bed now containing 10.0% granulation and 90.0% epithelial tissue.

Exudate levels were low, and the peri-wound skin was intact and no longer fragile. By week 4, the wound had completely healed. Oedema in the limb was effectively treated, and noticeable skin changes because of venous disease also improved (Figure 4). The patient's QoL score improved from 50 to 10, and her pain score decreased from 8 to 1.

As the wound improved and reduced in size, the patient gained reassurance that the wound could heal, which significantly alleviated her stress and anxiety. She was able to resume baking and caring for her grandchildren. In her own words:

‘I am so happy with the compression wrap. I did not want to have bandages as I suffer from eczema and would not be able to apply my creams to my limb. The compression wrap meant I could shower, apply my creams, and my husband could easily reapply the wrap safely.’

From a clinical perspective, the wrap was simple to apply and offered flexibility with three levels of pressure: low, medium or high, depending on the patient's clinical presentation and pain levels. In this case, full pressure was applied and the patient found the wrap extremely comfortable. Its ease of application also supported self-care, freeing clinicians’ time in an already stretched healthcare system.

Case study two

Management and healing of a chronic non-healing leg wound in a 50-year-old patient

Joy Tickle, Tissue Viability Nurse Consultant

A 50-year-old man presented to the practice nurse with a chronic, non-healing leg wound that had persisted for 6 months. The ulcer developed spontaneously, with no reported trauma to the limb. His medical history included atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, lipodermatosclerosis and venous disease affecting both limbs. The wound had a significant social impact, causing considerable pain and anxiety. The patient faced challenges at work because of time off for wound infections and clinic appointments. Despite wearing compression hosiery, the ulcer was failing to heal. The patient was extremely embarrassed by the wound, as it would sometimes become malodorous and occasionally leak out of the dressings. This negatively affected his relationship with his wife, to the point where he would often sleep in a separate bed to avoid the discomfort caused by the wound. The patient also expressed that he would prefer to dress the wound himself rather than attend twice-weekly clinic appointments.

The patient was knowledgeable about his venous disease and understood that compression therapy was essential for managing the condition and promoting wound healing. While he was compliant with compression hosiery, he was disappointed that it had not facilitated healing of the wound. It was explained to him that full compression therapy was required for optimal healing; however, he was reluctant to use compression bandages because of the continued dependency on clinic appointments. At this point, supported self-care was discussed, and the Biflex wrap system was introduced.

Before treatment, the patient's QoL score was 60 (on a scale of 10–70, with 70 representing the most significant impact on QoL), and his pain score was 7 (on a scale of 1–10). His medications included Zopiclone 7.5mg, Digoxin 125mg, Depomedrone 10mg and Venlafaxine 75mg slow release. Previous treatments had included antimicrobial primary dressings and antibiotic therapies. The wound failed to reduce in size, measuring 40mm by 40mm, with a 100% haemopurulent wound bed and exudate (Figure 5). There was a risk of reduced healing because of the patient's venous disease and history of pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis, as well as the associated medications. The exudate levels were low and the surrounding skin was desiccated and unhealthy, with the peri-wound skin being broken.

The new treatment regimen consisted of cleansing the wound with normal saline, applying an UrgoStart Plus pad as the primary dressing, using emollients for the surrounding skin and introducing the Biflex compression wrap system. The patient was able to apply the wrap with full compression independently, with support from the practice nurse. Over the course of 4 weeks, the wound responded positively to the treatment. By week 4, the wound had completely healed (Figure 6). The patient's QoL score improved from 60 to 0, and his pain score decreased from 7 to 0. As the wound improved and reduced in size, the patient became more confident and less anxious. The wrap system allowed him to tailor his dressing changes to fit his work and home life commitments, increasing his independence. The patient was highly satisfied with the outcome, stating that the wrap system was amazing.

‘Not only did it heal my wound, but my leg swelling also improved significantly, and best of all, I could carry out my own treatments without taking time off work. I can pretty much say my life is back to normal. Thank you.’

Conclusions

Biflex Self Adjust compression wrap is an important new option for patients with chronic oedema and CVI. From a clinical perspective, the wrap is simple to apply and offers flexibility with three levels of pressure depending on the patient's clinical presentation and pain levels. Its ease of application also supported self-care, freeing clinicians’ time in an already stretched healthcare system. CVI and lymphoedema cause important clinical and economic challenges for the NHS, cause poor QoL for patients and can lead to ulcers, infections and other serious sequalae. Compression is the cornerstone of treatment of lymphoedema and CVI, and the choice of compression wrap is important to maximise adherence and optimise clinical and economic outcomes.