Prescribing in healthcare has historically been a doctor's role. The number of non-medical prescribers, including nurses, pharmacists and allied health professionals, has rapidly increased since 2002 (Brett and Palmer, 2022). However, there is limited data on the significance of non-medical prescribing (Cope et al, 2016). Quantitative data underscores the benefits of non-medical prescribing, particularly in terms of cost reduction and timely treatment. However, a systematic review of nurses, physiotherapists and pharmacists revealed a notable reluctance among non-medical prescribers to engage in prescribing (Edwards et al, 2022). This is despite individual learners completing a comprehensive and thoroughly assessed prescribing course to become non-medical prescribers (Maddox et al, 2016).

Non-medical prescribing was introduced to improve patient safety and professional autonomy (Stewart et al, 2017). Weeks et al (2016) discovered that patient outcomes were equally favourable when cared for by a non-medical prescriber, as compared to their medical counterparts. In an already strained healthcare system, it is essential to deploy non-medical prescribing skills within clinical practice and to identify solutions to the obstacles that impede this practice.

There are limited firsthand accounts examining the perceived and actual barriers faced by healthcare professionals who are new to prescribing, and little is understood about how these experiences impact the confidence and preparedness of student non-medical prescribers.

The independent prescribing programme at the author's university is similar to many across the country, requiring students to meet the regulatory, educational and clinical practice standards for prescribing practice outlined by the General Pharmaceutical Council (2022), Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (2019a), Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2024) and Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2021). Professional annotation of this standard is legally required for a practitioner to prescribe and successful completion enables students to have their non-medical prescriber qualification registered with their regulatory body. The prescribing programme that awards this qualification must be accredited by the student's professional, statutory and regulatory body (Health Education England, 2018). New skills and high levels of advanced practice prescribing demands makes it essential for students to receive proper education (Boreham et al, 2013). Therefore, these prescribing programmes must reflect the same high standards of quality to help prepare students.

Literature review

Some challenges were anticipated when searching for literature relevant to this topic. There are many different titles, terms and professions to consider when defining an independent prescriber (Blaber et al, 2020). This created inconsistency because much of the available literature excluded certain professions or areas of practice (Graham-Clarke et al, 2018). This can be prevalent when professions differ in priorities and approaches, particularly in education (Yau et al, 2021). When specifically examining confidence in prescribing, Courtenay et al (2007) noted some emphasis on those supporting or supervising prescribing students. Conversely, Tinelli et al (2013) conducted a survey that examined the patients’ view of non-medical prescribing. It is also worth noting that despite a thorough examination of available sources, both these studies are from some time ago; a factor that could affect the validity of findings for contemporary non-medical prescribing practice learning. During the last 3 to 5 years, the healthcare landscape has dramatically altered (also because of the pandemic) (Vindrola-Padros et al, 2020).

There were also professional limitations; most of the data relevant to the challenges of prescribing was focused on doctors and medical students (Weiss, 2021). Furthermore, a comparative study done by Brinkman et al (2015) contrasted perceived self-confidence in prescribing against assessment and achievement for medical students. It yielded interesting results, showing a poor correlation between the two. This highlights the significant gap and potential missed opportunities in research regarding confidence in medical versus non-medical prescribing.

Some literature denoted prescribing confidence amongst allied health professionals, but concentrated on traditionally pharmacological-based professions only, such as pharmacists. One literature review focused on confidence in prescribing, but only in the context of pharmacists and doctors (Woit et al, 2020). The gap in the available literature on this topic across professions is at the risk of widening because of the Standards for the Initial Education and Training of Pharmacists (General Pharmaceutical Council, 2021) reform, enabling pharmacists to become prescr ibers at qualification from 2026 (Channa, 2021). This may intensify the spotlight on pharmacist non-medical prescribers.

Significant portions of the available literature look into confidence levels, specifically in connection with global prescribing challenges, such as antimicrobial resistance, the opioid crisis and contraceptive prescriptions in studies by Haque et al (2022), Ivanics et al (2021) and Lynch et al (2020). Prescribers’ influence over these (for example, antimicrobial stewardship and other public health considerations) is substantial (Babashahi et al, 2023). However, this excludies 50 693 nurses (NMC, 2021), 171 paramedics (HCPC, 2019b), 1295 physiotherapists and 442 podiatrists (Carey et al, 2020).

There are instances in literature of professions that prescribe, but are not necessarily traditional prescribers. By using blended learning and examining the literature, Walls (2019) looked in detail at the experiences of community nurses when prescribing and specifically the education process underpinning this. Findings indicated that confidence was impeded by the limited integration of pharmacology and advanced physical assessment within the nursing training curriculum.

However, this may be addressed over time as, under the most recent Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses (NMC, 2018), newly qualified nurses must have greater proficiency in diagnostics, assessment, care planning and pharmacology. Other compounding factors may be barriers such as non-medical prescribers experiencing ‘imposter syndrome’ and professional identities. Jarmain (2022) found through interviews with non-medical prescribers that participants felt that they were emulating a doctor's role at times and there was also a lack of role models to seek support from (professional peers who prescribed).

Contrary to this, McHugh et al (2020) conducted interviews and found that nurse prescribers felt interprofessional prescribing to be beneficial. They described consultants and pharmacists as ‘supportive’ and could see the benefits of non-medical prescribers, both for balancing workload and increasing accessibility to treatments.

Despite its limitations, the literature identified facilitators and constraints that could be translated to other health professionals. These include fear of prescribing errors and increased responsibility, lack of resources and time, organisational influence, and lack of training in diagnosis and physical assessment.

There is a lack of studies that explore the experiences of non-medical prescribing student and how it affects their level of confidence. Additionally, much of the literature does not integrate findings across professions or areas of practice, making it difficult to identify gaps in the curriculum (Edwards et al, 2022). This further highlights the need for more research into the impact of pedagogy on non-medical prescribing.

Method

At the author's institution, independent prescribing is a level 7 only programme and applicants must have at least 3 years’ post-registration experience in their field; studied at level 6 in the last 5 years; and completed a physical assessment (or equivalent) module. The NMC prescribing standards specifically require at least 1 year of post-registration experience, while both the NMC and HCPC emphasise the need for appropriate clinical and academic experience (HCPC, 2019b; NMC, 2024). Therefore, potential participants are highly likely to be proficient practitioners before they begin the non-medical prescribing programme.

The purpose of this research project was to identify the facilitators and, or, constraints encountered by students, while assessing how well the university's prescribing programme was preparing them for these challenges. The approach to meet these goals was a mixed-methods study, with an emphasis on obtaining qualitative data, which can provide a deeper context when investigating behavioural and experiential data (Ritchie et al, 2014).

There were two focus groups with of four to eight people, with pre-prepared questions and discussion points; one group with specialist practice qualification (SPQ) students and one group with advanced clinical practice (ACP) students. The focus groups were 45-minutes long, held on university premises and attended by the students. The author facilitated each session and a fellow module team member was present to take notes during the session. The session was also recorded on Microsoft (MS) Teams for the author to refer to after the focus groups had concluded; automatic transcript on MS Teams was also enabled.

A consent form was generated in accordance with the university's ethics policy. Sample questions were based on the author's knowledge and experience of prescribing, themes discovered in the literature search, previous students’ feedback and in line with the standards set for independent prescribers in accordance with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2021) competency framework.

To cover a breadth of practice areas, students were selected from the community nursing SPQ course and the ACP course. The purpose was to find out if the students felt that the programme had adequately equipped them to start prescribing and to compare the perceptions of students on the SPQ course and those on the ACP course.

There were challenges in the recruitment of ACP students, however this setback allowed the focus to shift on SPQ students and revealed important themes. This was deemed appropriate as the SPQ course at the author's university had undergone significant transformation, after recent approval through a quality assurance event with the NMC (2020).

This included integrating the more advanced independent prescribing (V300—enabling practitioners to prescribe anything from the British National Formulary within their scope of practice) programme, instead of the community practitioner nurse prescribing qualification (V100—which enables prescribing from the Community Practitioner Formulary only) (Royal College of Nursing, 2023). This move was supported by local practice partners and national bodies, including the Queen's Nursing Institute (2015) and Health Education England (2015). This represents a major shift that requires careful consideration in delivering support to students; however, it will ultimately benefit both students and patient outcomes (Downer and Shepherd, 2010).

Recruitment

The author attended lectures on both courses to advertise the study and offered their email address to interested students. When they contacted the author, they were provided with a participant information form. In addition to adhering to the ethics process, the questions and participation sheet was also reviewed by the current prescribing module lead. The ethical risk score was low and required Tier 1 review. The risk involved pertained to potentially sensitive issues and recalling difficult experiences, which can often occur when reflecting on practice (Agnew, 2022). This risk was communicated in the participant information sheet and the offer of withdrawing from the focus group and signposting to support was provided.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethics committee at the author's university. A consent form and participation sheet were created to inform the participants. Students were offered support systems for any sensitive issues that could possibly arise and they also had the opportunity to leave at any point.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In total, nine students undertaking the SPQ pathway participated in the study. The inclusion criteria included students who would be finishing the programme within the next 3 months and were on the SPQ or ACP course. The exclusion criteria were for any students taking the programme as an individual module and not on either of the above courses. The rationale for this was to foster consistency and comparability by looking at groups with similar academic background and learning environments within the timeframe of the research project. Due to a lack of uptake by ACP students, these findings relate only to students undertaking the community nursing specialist practice course, aiming to work as district nurses after the completion of their course.

Findings

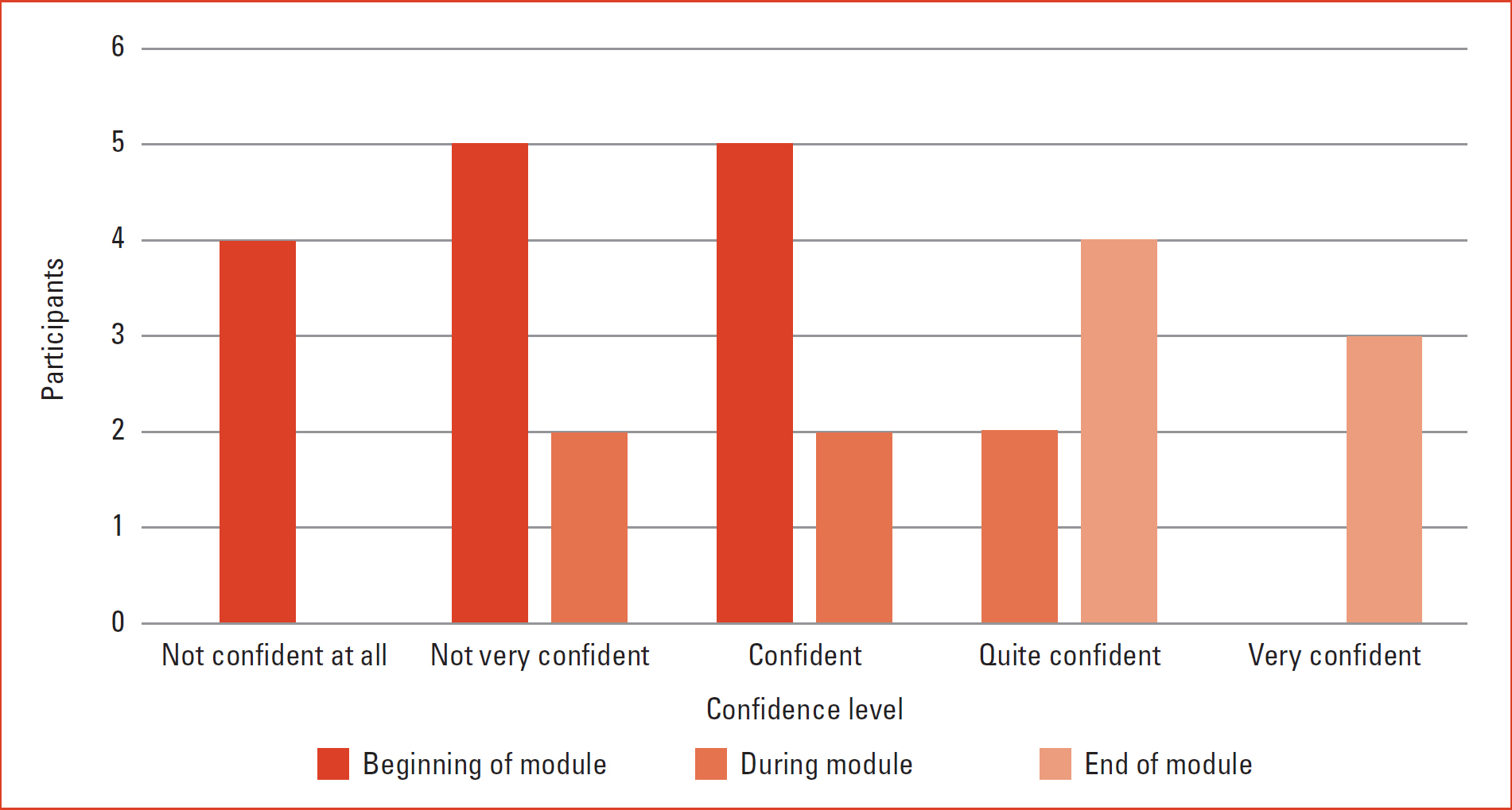

The study included a minor quantitative element. By combining both qualitative and quantitative, a more holistic view can be captured, particularly in complex scenarios where human factors are at play (Cohen et al, 2018). The Likert scale was used by the participants to rate themselves from 1 to 5, based on three questions (Table 1). Each student was asked to complete this score before taking part in the focus group. The results are given in Figure 1. Even before collecting the qualitative data, there was a clearly positive correlation between the increase of prescribing confidence from the start to the end of the module. However, as with any curriculum, there is always room for improvement in enhancing student experience (Race, 2019). While this is an important insight, it does not provide the context required when analysing a complex psychological state such as confidence (Lambert, 2019).

Qualitative Data

To obtain further in-depth data on confidence levels, the focus groups were asked sample questions (Box 1). It became evident that there were nuances to levels of confidence and it depended on what was being prescribed:

Focus group sample questions

‘I always felt really confident in prescribing dressings, but when my name was on it, all of a sudden I started questioning myself.’ (Participant 1)

| How confident did you feel with prescribing? | Not confident at all | Not very confident | Confident | Quite confident | Very confiden |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At the beginning of the module | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| During the module | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| At the end of the module | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

The weight of responsibility of prescribing was a significant factor in confidence levels among all participants:

‘I felt really well-supported by my assessor and felt confident when prescribing with them. But I think when I go out on my own, it will feel really different and scary.’ (Participant 2)

The concept of lone prescribing was also a common theme; the transition of losing the ‘safety net’ and being unsure of the availability of support networks afterwards. There same participant also drew comparisons between being a new prescriber and being a new nurse:

‘It would be nice to have competencies signed off when you start prescribing, like when you are a new nurse.’ (Participant 3)

‘I have two prescribers on my team; one of them does not prescribe at all—she does not feel confident. I feel that I will have to use the rights or lose them.’ (Participant 3)

Some participants gave examples of practicing colleagues, who were already prescribing. There was clear evidence of lack of confidence observed in experienced practitioners, which could either be demotivational or motivational for the newcomers, depending on the individual:

‘It would be handy to have a person, like your practice supervisor, to check in with.’(Participant 3)

‘I have no one in my team who can prescribe; there are only a few in my whole area. It is really daunting.’ (Participant 4)

It became immediately evident that there were few other prescribers to offer support. The students highlighted how their predecessors undertaking the SPQ course only needed to complete the V100 course (community practitioner nurse prescribing that equipped them with the limited nurse prescribing formulary). This resulted in a limited pool of prescribing practitioners, who met the practice assessor requirements set by the NMC (2024) standards for prescribing programmes.

This cohort of students was completing the full independent prescribing course, as an integral part of the SPQ course. They pointed out that this was a new phenomenon in the area and often referred to themselves as ‘guinea pigs’. Out-of-hours practice time was also identified as an exacerbation of these issues, as fewer experienced prescribers were available at the weekends or in the evenings. In addition to problems with persons assigned to support them, there was some concerns regarding the available clinical placements. For example, being placed with a practice supervisor or practice assessor in acute areas, when their normal place of work and scope of practice was entirely based in the community:

‘I think some of the prescribing experiences were not so relevant. Sometimes we were in acute areas that were interesting, but would have been better after more experience.’ (Participant 2)

The group agreed with this perspective, noting that while exposure to other areas of practice is valuable, it would have been more beneficial to schedule these experiences closer to the end of their prescribing programme or after its completion. Two participants attributed this to the limited number of independent prescribers within their trust and the community setting, which required their supervisors to be resourceful in providing opportunities. Courtenay et al (2012) found that community practitioners generally prescribed less than their secondary or primary care counterparts, to some extent because of reliance on supplementary prescribing or referral to general practitioners. However, the group recognized that independent prescribing is an expanding field in the community, suggesting potential for improvement in the future:

‘The programme helped me identify people and specialists who can support me in making prescribing decisions. One should not be making those decisions alone; this is not what an independent prescriber does.’ (Participant 5)

Participants shared some interesting perceptions about what it means to be a prescriber, noting that the programme reinforces interprofessional working practices and discouraged working in isolation. When asked about safe prescribing practices, participants expressed confidence in their ability to access local policies. In discussing challenging prescribing situations, participants highlighted common themes consistent with existing literature, including antimicrobial resistance, remote prescribing and patient expectations. They credited the module for preparing them for this through teaching sessions and signposting to appropriate guidelines. There was robust critical discussion around deprescribing and rationale, both of which are key learning points in the module:

“I do feel like the course has made me think about my practice a lot more, which is great, but I also overthink sometimes.’ (Participant 4)

This comment demonstrates the duel-faceted potential of the module. While encouraging students to be more critical of their own practice, it also runs the risk of impeding confidence. However, some of the participants felt the module had improved their overall practice:

‘I look at everything in more detail now, after doing the module. Before, I would not question much when asking for prescriptions. Now I really look into the finer details.’ (Participant 3)

‘The pharmacology in the module really helped me understand the importance of how drugs work with each other; it was the most important takeaway from the course for me. The knowledge has given me confidence in practice.’ (Participant 6)

Discussion

The themes identified in both the Likert scale and the focus group included a blend of expected and unexpected findings. Many of the issues raised were consistent with those encountered by other professions when they began prescribing. The most prominent theme was the importance of support in practice for prescribing. Students noted that some prescribers lacked the confidence to undertake the roles of practice supervisors or assessors. Additionally, they expressed a preference for learning opportunities earlier in the programme that focused on prescribing within their specific professional context, particularly in-home settings. They suggested introducing shadowing in other practice areas later in the programme, enabling them to observe, critique and compare prescribing processes across different environments. There is perhaps work to be done on building closer working relationships between universities and practice partners to further discuss learning opportunities and the requirements for practice supervision for district nursing students engaged in this training.

The Likert scale data and student feedback indicated a strong sense of preparedness during the programme. The knowledge shared in the programme translated to ‘real-world’ practice. Participants felt the need for a transitional phase-similar to the way newly qualified nurses are supplied with ‘preceptors’ when they first begin working independently (NHS England, 2022). While the university has stipulated that SPQ students should have a period of preceptorship in their new role, students reported that these were often other than non-medical prescribers because of the small numbers available. This indicates that a more robust and explicit process may be required.

It could be a consideration for future iterations of the programme, in terms of recommendations for practice partners supporting the students. These participants were the first group to undertake the full independent prescribing module at the university, as part of the SPQ course. Therefore, it is worth noting that the limited availability of appropriate supervisors and placements may naturally improve as more prescribers qualify locally.

Limitations

The viewpoint of students from the ACP pathway would have been beneficial, as this would provided insights into the experiences of learners undertaking non-medical prescribing from a wider variety of clinical settings, such as primary and secondary care. This would have enabled the study to go deeper into community specific issues for nurses who are on the community specialist pathway.

However, this runs the risk of emulating previous studies, where profession-specific research can produce narrow results. This was a very small-scale study in terms of both size and time. A larger sample group (including ACP students) would be beneficial in identifying additional issues in other areas and exploring them in greater depth. A follow-up study on analysing whether the realities of becoming an annotated prescriber aligned with their fears, perceptions and experiences would also provide valuable information.

Conclusions

While much of the existing evidence is outdated, it is encouraging to discover that since the original studies highlighted in the literature review, supervisors and placements have become more supportive and encouraging of prescribing students.

Some students felt that their prescribing practice opportunities were not always optimised to their learning, owing to the lack of independent prescribers in the community and increasing NHS pressures. One thing is consistent in both the literature and this study: after they qualify as a non-medical prescriber in clinical practice, students have to find their own way in what is a recent and formidable forum.

Universities providing independent prescribing programmes may support students better by incorporating a professional competency development component. This could include continuous learning through regular workshops, structured supervision programmes with experienced prescribers and reflective practice sessions. From an employer's perspective, ensuring necessary support structures for newly qualified prescribers is equally paramount. This can be achieved through the development of personal formularies tailored to specific practice areas, regular supervision and monthly check-ins with senior prescribers, easy access to clinical guidelines and decision-support tools, and systems for regular feedback from supervisors and peers. This two-pronged approach would provide ongoing support, even after the completion of the module and help navigate their new role as a prescriber. To identify more potential solutions to some of these challenges, the non-medical prescribing curriculum is a frontier that requires closer examination.