The treatment of diabetes within the community has undergone radical change over recent years with the launch of new therapies, including new insulins, bio-similar insulins and incretin mimetics (Smyth, 2020). At the same time, organisations have made changes to workforces through skills mixing and reorganisation of services, resulting in a need to delegate the administration of insulin, safely, to a wide range of different staff working at varying grades, including assistant practitioners, nurse associates, health care support workers and, additionally, care home staff. To support these changes, a range of resources have been made available nationally, including e-study modules, such as ‘Insulin safety e-learning’ (Trend Diabetes, 2020) and ‘An integrated career and competency framework for adult diabetes nursing’ (Trend Diabetes, 2021), together with ‘Competency framework and workbook: blood glucose monitoring and subcutaneous insulin administration’ (NHS, 2020).

The trust under discussion is a community health services provider that spans both an urban and large rural area. Among other services, it provides a community nursing service to a population of approximately one million, working alongside 136 GP practices. Over a number of years, both the trust and GP practices have undergone radical change. Inevitably, this has led to some impact on custom and practice, including old documentation devised locally when nursing teams were linked to GPs still being used, alongside handwritten forms. Illegible handwritten forms have contributed to errors.

Across the UK, six Never Events—clinical situations that should never occur, such as the retention of a foreign object, for example, as swabs in a patient after surgery—relating to an overdose of insulin due to the use of abbreviations or use of an incorrect device were recorded between 1 April and 30 November 2021 (NHS, 2022). Analysis of local data demonstrated that community nursing services were involved in 24 insulin errors from January to May 2020, including one Never Event. A total of 41 997 episodes of care involving insulin were carried out in the same period. The data demonstrated that the errors were related to missed doses (ten), extra doses (five), incorrect doses (five) and incorrect insulin use (four). Further analysis completed by the author through an internal audit of district nursing documentation and discussions with staff was able to demonstrate that a range of causative factors were in play. These factors were as follows:

- Unclear allocation of patients

- Staff shortages leading to an excess of patients requiring visits for the administration of insulin at the same time

- Unclear or out-of-date insulin authorisations from prescribers

- Outdated nursing care plans

- A lack of knowledge regarding the range of insulins being administered

- An inadequate drive to assist patients to become independent in their own insulin administration when taken onto caseloads

- Duplication and process issues in relation to electronic and paper documentation

- Transcribing of doses

- A general lack of ownership for the care of the patient with the demise of named nurses.

In order to begin to address the issues, a decision was taken to use a Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycle (Moen and Norman, 2010). The PDSA model for improvement provides a framework for developing, testing and implementing changes designed to lead to quality improvement (NHS, 2021). There are four key stages to testing change ideas within the PDSA cycle, which are:

- Plan: this is the change to be tested

- Do: carry out the change

- Study: compare the outcome with the intended outcome and reflect on the learning

- Act: this is a renewed plan based on the observations and learning.

Using PDSA cycles enables fairly rapid testing on a small scale, prior to wholesale implementation. Stakeholders have the opportunity to see if the proposed change will succeed, making it a powerful tool for learning from ideas that do or do not work. This way, the process of change is safer and less disruptive for patients and staff.

Within the author's study, overall success was measured using a staff questionnaire. This comprised five key questions and was repeated both prior to and following the change. Strategically, incident numbers were closely monitored to identify when a downward trend in incidents began to occur and if it was sustained.

Change theory and practice

Effective change is best implemented by ensuring that those affected by the proposed changes have a voice as part of the whole process. A sense of shared purpose is thus created, which focuses on why the change is required, not what the change is or how it might be implemented (NHS, 2018). Therefore, it was important to ensure that staff were engaged from the outset. While high-level analysis identified the themes underlying the insulin incidents, an electronic staff survey confirmed what was already known. The link to the survey was sent using staff WhatsApp groups and email links, and through announcements during team meetings. Responses were completely anonymous, with only the grade and nursing hub of staff being identifiable. This approach encouraged staff to offer their views at a time suitable to them, safe in the knowledge that they could be candid. In addition, anecdotal evidence was gathered by the author through discussions with staff who were involved, both directly and indirectly, in incidents. The discussions highlighted not only the safety of patients, but also the human cost of errors for staff in relation to the loss of clinical confidence, the need for emotional support and the impact on colleagues covering visits when a member of staff was undergoing support training.

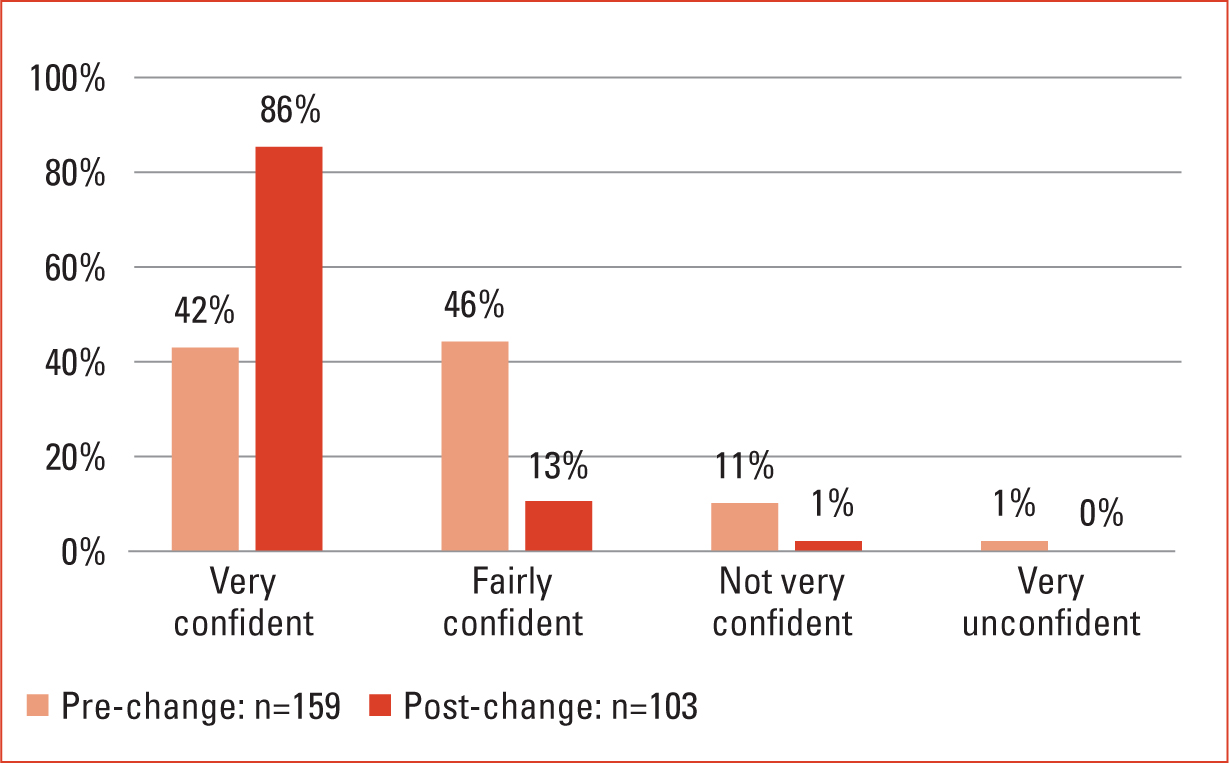

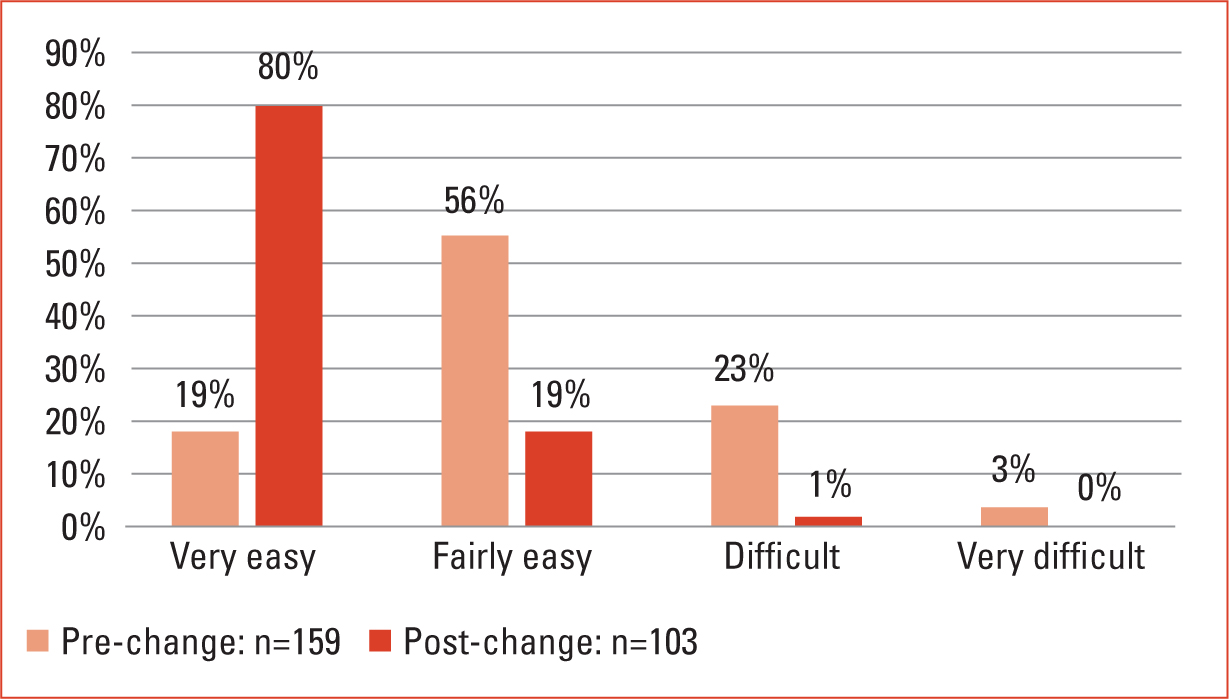

The results of the electronic survey (Figures 1–5), alongside the high-level analysis of incidents and the anecdotal evidence gathered, allowed a small project team to begin to design a package of changes to address the identified issues. The overall aims of the project were to reduce insulin administration errors and improve patient care by providing clear management plans, while increasing staff confidence and knowledge. This was to be achieved by implementing clear processes and redesigning documentation.

Development of the package of changes

When making change, it is useful to draw on the lessons of the past. Large-scale changes to ways of working had previously been implemented within the organisation in relation to managing, authorising and documenting the use of controlled drugs in patients' homes. Those changes were successfully implemented and crossed professional and organisational boundaries between the district nursing service, GPs and the local hospice. In this respect, the proposed changes and challenges around insulin management and administration could be perceived as similar.

The organisation is paper-light, and patients have only ‘essential’ records kept in their homes; all other records are stored electronically. Staff should access electronic records in the patient's home using laptops. However, poor connectivity, lack of battery life and long loading and start-up times all mean that staff do not always have ready access to the electronic record. Medication administration records are seen as essential documentation; therefore, these records are stored in the patient's home. By enquiring which documentation staff were currently working with, it was evident that documentation was still being used from legacy organisations. Prescribers, such as GPs, were using a range of insulin authorisations; medication administration sheets were re-photocopied, leading to poor printing copy; and patient paper records were disorganised. A decision was taken that, for patients in receipt of insulin administration, or being prompted or taught to self-manage, the organisation would revert to a comprehensive package of revised paper documentation, while keeping the electronic records updated. The following package was developed and piloted as part of the PDSA cycle after wide consultation with frontline staff:

- An A4, branded, wipeable, hard-backed ringbinder was introduced, which included eight wipeable tabbed plastic inserts with specifically named sections to aid navigation and filing.

- A redesigned administration of insulin record was implemented. It is made of blue card in order to stand out, professionally printed and linked to the five Rs of medicines management (the Right drug is given to the Right Person at the Right Time at the Right dose via the Right route) (Boyd, 2022). The record contains all the information for a prescriber to effectively review capillary blood glucose control. Permission was sought to base the new form on an existing one taken from an NHS Trust exemplar site. This was developed further to incorporate the 5Rs and a stock check of insulin pens and vials in the patient's home.

- A sheet that offers an insulin profile ‘at a glance’ was introduced. It is printed in full colour and outlines the key facts about the particular insulin being given to the patient.

- A single, standardised insulin authorisation form is now created electronically by the prescriber and is locked onto the patient's electronic record. It is also printed and placed in the aforementioned A4 folder. The authorisation is the sole form informing the nurse of the dose and type of insulin to be administered, alongside when the insulin is to be given. It contains the escalation plan and target capillary blood glucose readings for the patient. This was the only part of the change that crossed organisational boundaries to GP practices.

- A revised process was implemented to ensure that the very latest insulin authorisation is placed in the patient's home in a timely manner.

- Revised care plans were also introduced, replacing a single care plan with a choice of three that clearly signal the purpose of the visit being either to teach the patient, prompt the patient or instruct the nurse to administer insulin.

Consultation of staff did not simply involve nurses and healthcare support workers, but also members of the nurses' administration teams and the information technology (IT) department. In addition, wider consultation was made with GPs and Diabetes Specialist Services (Diabetes Nurse Specialists employed within the local Acute Hospital Trust) in relation to the concerns around insulin authorisations. Consulting stakeholders in the right way is critical to ensuring engagement in the proposed change, and to improving the likelihood of creating a sustained and successful change (NHS, 2009).

Piloting the project

The community nursing service is split into eight community nursing hubs that work across the region. One inner-city hub was chosen as a pilot site, with one team within the hub selected to spearhead the new documentation and processes.

In addition, it was decided that it would be prudent to classify the whole project into three distinct parts. Insulin authorisations would impact primary care and formed one part. Revised care plans would impact district nurses and were seen, internally, as a quick win. However, work around both of these involved IT teams, clinical commissioning subgroups and practice managers. Finally, the folders and blue insulin administration forms required sourcing, purchasing and printing, involving procurement teams and budget-holders. Production of the insulin profile ‘at a glance’ sheets were created with the help of the diabetes nurse specialists in the local acute trust and the pharmaceutical companies concerned.

Throughout the process, staff were kept informed of changes using a range of methods, including email, WhatsApp bulletins, trust communication sheets and media clips on YouTube. Additionally, and importantly, key personnel were co-opted to ensure that local actions actually took place. Managing local action required the use of progress sheets (Table 1). The progress sheets allowed the project group to monitor progress in the pilot site and in other teams and hubs after the pilot had ended and wider implementation had begun. Assurance was required that every patient was reassessed by a senior nurse with, when needed, the assistance of a diabetes nurse specialist. This was to ensure that only those patients who really needed district nursing input were kept on the caseload. Systems are in place to move patients towards independence. Staff were provided with a letter they could give to families if it was deemed that a person could be supported by a family or be independent, but were reticent about doing so. Only once these steps had been taken could the nurses request one of the new standardised insulin authorisations from the GP/prescriber.

Table 1. Progress sheet format

| Insulin documentation roll-out in X area | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date updated: | |||||||||

| Patient's surname | Patient's first name | NHS number | Holistic assessment date | Assessed as able or unable to self-care | Self-care letter given (Y/N) | New insulin authorisation date | New care plan date | New care plan date | Dates new notes were taken |

Implementation

Implementation was commenced once it was clear that any issues had been negated as far as possible through using the pilot site and the PDSA cycle. Implementation was phased hub by hub, ensuring a small bedding-in period was given prior to moving on to the next hub. As the PDSA cycle continued to be used during implementation, the process could, if required, be halted and any concerns dealt with in a timely manner. The prescribers who were being asked to use the newly created electronic insulin authorisations were given quick reference guides, which helped them find and complete the forms within the patient electronic records. In addition, they were sent a link to a YouTube media clip and a letter explaining the patient safety reasons for the changes to practice. The author committed a large amount of time to speaking to practice managers, GPs and nursing teams to reinforce the need to ensure full understanding of why the changes had been brought in.

Electronic staff survey questions with associated results, before and after change implementation

As previously stated, two identical surveys were run, both before and after changes had been implemented. Each survey included five questions and aimed to understand how confident nursing staff felt about the previous way of working when compared to the new systems and documentation. The survey included a question about staff knowledge of insulin (Figures 1–5).

Findings

The results demonstrated in Figures 1–5 show clear positive changes in nurses' confidence both towards the revised insulin authorisation forms and the new package of nursing documentation. There are marked improvements in confidence and knowledge due to the implementation of insulin profile ‘at a glance’ sheets. While showing improvement, it can be seen that there is still work to be done in regard to nursing care plans, giving staff the confidence to be sure of the purpose of their visits to patients. While these results were generated by the two anonymous surveys employed, the author found these were also verified during informal discussions with staff. Separately, organisational governance audits demonstrated an overall reduction in insulin errors, with those that occur being the result of a failure to adhere to process. Incidence of errors is not spread equally across every nursing hub and tends to occur where there are unstable teams. Throughout the entire duration of the project, the workforce has been working under restrictions and circumstances dictated largely by the COVID-19 pandemic. This in itself has led to challenges in both caring for patients in the home and in implementing change.

Conclusion

Organisations must take ownership of the patient safety concerns occurring within them. This article has aimed to demonstrate that creating effective change is achievable and will benefit not only patients, but also the staff caring for them. Change needs to be sustained and consideration needs to be given to how this will be enabled. Francis (2013) states that the team leader is ‘critical to the delivery of safe patient-centred care’. Locally, it will be team leaders and district nurses who will need to ensure that staff adhere to the processes that have been put in place.

The changes described in this article were expected to take around 6 months; however, it took over a year to embed transformation and begin to see sustainable change. Ideas that seemed simple required process mapping, negotiation, procurement and clear oversight, alongside a lead who was given dedicated time to ensure completion of the planned change. It could be argued that many organisations fail in creating sustained change as they simply tag project management onto an existing person's job, rather than viewing the project as a standalone piece of work than requires planning and dedicated time. Possibly the greatest lesson learnt was to ensure that time was taken to engage with a wide range of staff upon who the changes would impact, fully understand their concerns and the reasons for errors occurring and, then, wherever possible, incorporate their suggestions into the PDSA cycle. This helped to ensure the sustained, positive change other organisations might be seeking.

Key points

- Effective change requires a full understanding of the reasons the change is necessary

- Understanding the views of those who will be affected by the change and demonstrating that their suggestions have been incorporated into the change will lead to a sustainable solution in practice

- Utilising a Plan, Do, Study, Act approach captures and records learning quickly, allowing for timely adaptations to plans

- Wherever possible, ensure a project lead is in place to have complete oversight of the process

CPD reflective questions

- What systems does your organisation have to identify patient safety incidents and trends?

- How would you go about ensuring your patient safety concerns are heard and acted upon?

- What do you consider to be the key considerations when delegating care to a nurse you do not know?

- Consider your own organisation's practice around insulin administration—do the processes in place support the most junior staff adequately?