Community health services have flourished since the introduction of the NHS England (NHSE) Long Term Plan (2019), and patient's home is now considered the most economical place to provide patient-centred care (NHSE, 2021). As part of the plan, it is a requirement that a diverse, multidisciplinary team (MDT) delivers a network of integrated community services. Therefore, in community settings, services are tailored to patients' needs to prevent hospital admissions, enhance quality of life (QoL) and support earlier discharge from hospital.

NHSE assigned each Trust a 2-hour urgent crisis response service within this web of services (NHSE, 2021); advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) and trainee advanced clinical practitioners (tACPs) provide advanced care and coordinate this initiative within community services, providing patients with advanced clinical skills at the point of crisis and delivering strategies based on evidence-based practice (NHSE, 2017).

The ACPs and district nurses (DNs) work with clients who need assistance with various medical issues. The DN or therapist may be the only healthcare provider who sees the individual as the service users are housebound. Thus, every contact is vital; comprehensive evaluations give them a critical chance to maximise the person's health, independence and QoL (Local Government Association, 2023). Health professionals document their consultations on an online Egton Medical Information Systems (EMIS), using templates for ease and ensuring essential assessment has been done in line with evidence-based practice (Aldoori et al, 2019). The trainee ACP (the researcher) noted few referrals for deep vein thrombosis (DVT). However, because of the lack of a structured template, the tACP struggled to collate data on the number of patients screened for DVT.

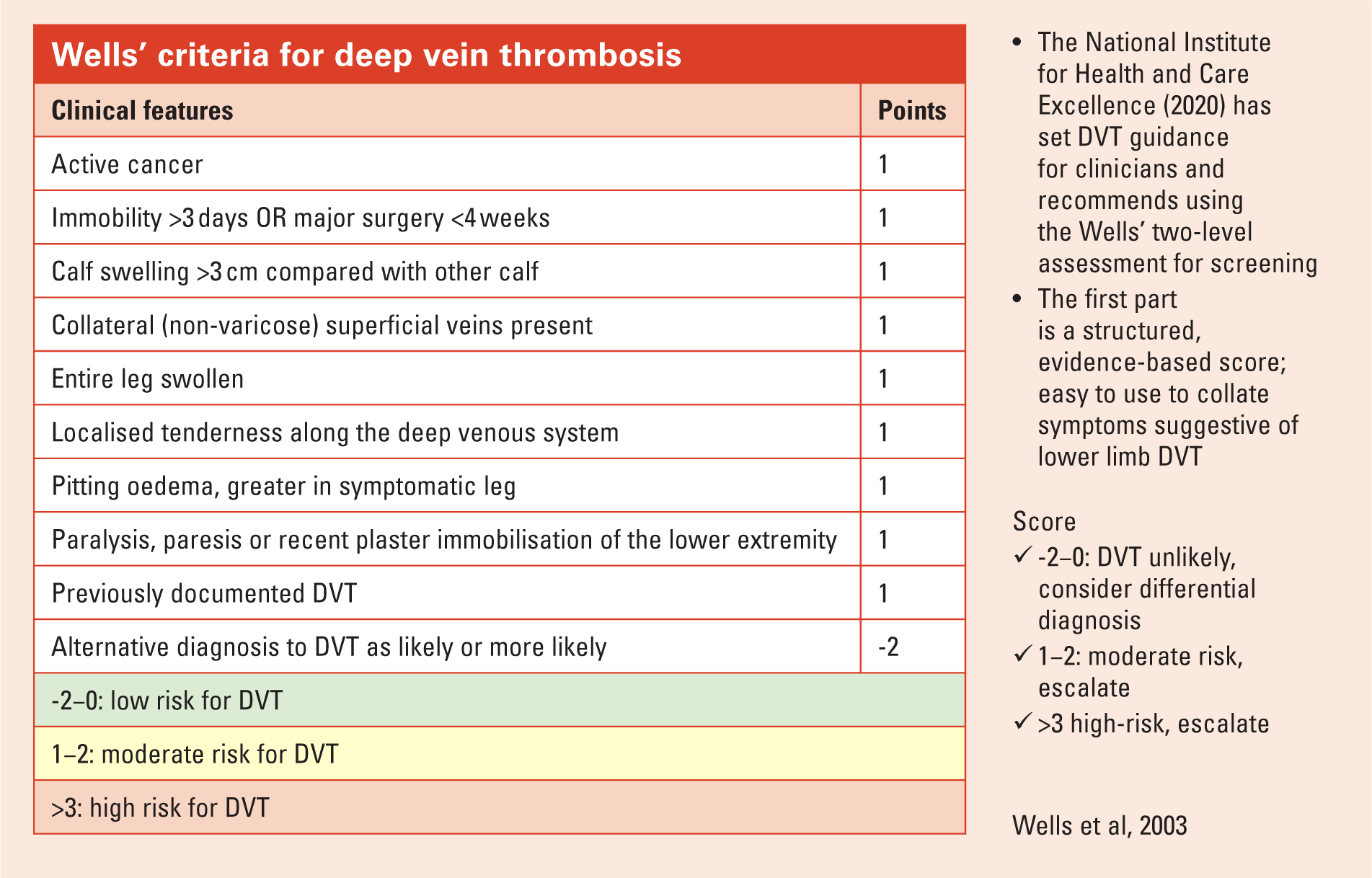

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2023) has established clear guidelines for clinicians regarding DVT screening. The Wells' 2-level assessment is a validated screening tool that is a simple, evidence-based score used to compile symptoms suggestive of lower limb DVT. The Wells' score provides the practitioner with evidence that the patient should be escalated (Stubbs and Mouyis, 2018). Wells' DVT screening has proven beneficial in ruling out DVT because it has a low rate of false negatives; it is valuable to rule out patients with a low Wells' score and avoid unnecessary interventions (Trihan et al, 2021).

Research question

How can community nurses and MDTs improve DVT screening and documentation in housebound patients?

Aims

To improve effective screening and documentation of DVT in housebound patients. The objectives are to introduce new interventions to improve screening and documentation.

Design

According to the Health Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP, 2015), several methodologies for quality improvement (QI) have similar characteristics and underlying assumptions that promote creative QI in quantifiable ways. The researcher adopted the 2-phase Model for Improvement (MFI) approach and project progress was monitored at prearranged Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (Public Health Accreditation Board, 2020).

Ethical considerations

This Quality Improvement Project (QIP) was reviewed and approved by the assigned academic supervisor (EthOS Reference Number: 63281) and written authorisation was obtained from related NHS trust. Congiunti et al (2023) regarded this action as a crucial research ethical practice. Data collected were stored and destroyed in line with the Data Protection Act (UK Government, 2018) and Trust Information Governance policy (NHSE, 2023a). Participants were contacted following ethical clearance. During the initial meeting, participants signed an information and consent sheet.

Participants

A total of 19 nurses, three occupational therapists, two physiotherapists, two ACPs and one healthcare assistant consented and participated in the training and audits. However, all of them did not participate in all the meetings because of work commitments.

Methods

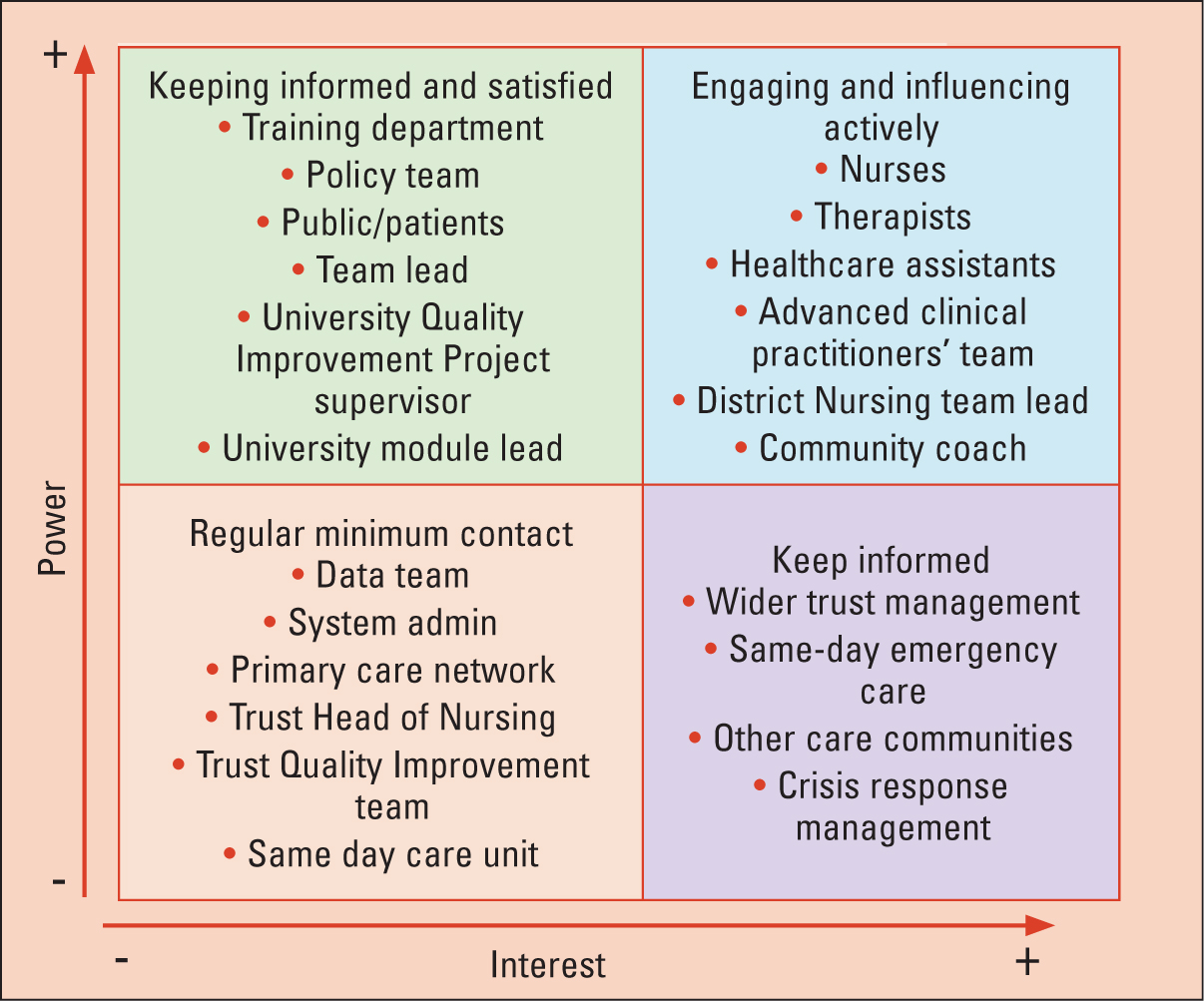

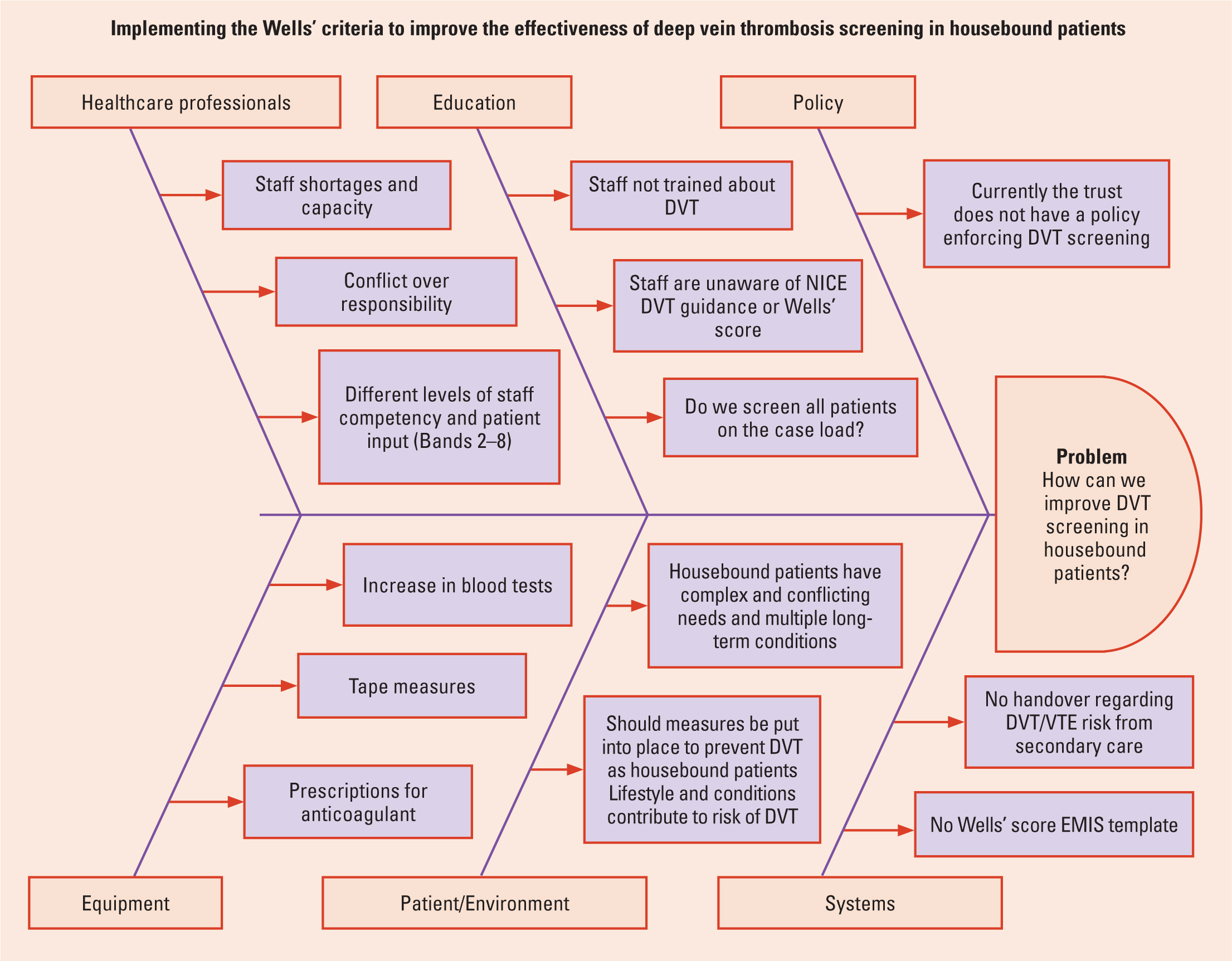

This project had two phases: the preliminary or context phase that lasted from September 2023 to February 2024 and the intervention phase from March to June 2024. Owing to the lack of objective data, the tACP performed an audit in September 2023 to check the staff 's understanding and involvement in screening for DVT. The staff members were identified as key stakeholders. Therefore, the trainee advanced clinical practitioner aimed for a collaborative approach with the team and conducted a stakeholder analysis (Figure 1) (Phillips et al, 2019). The project adopted the Model for Improvement methodology (NHS Improving Quality, 2015) (Box 1) with a fishbone analysis (Ishikawa, 2012) (Figure 2) and driver diagrams (Taylor and Bircher, 2022) to create and narrow down ideas. To implement these ideas, three PDSA cycles (Langley et al, 2009) were conducted. Using this experimental initiative, the QIP has a better chance for continuous analysis (Reed et al, 2016). The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) recommends that nurses work proactively to improve services through quality improvement methodologies.

Model for Improvement

The Model for Improvement (MFI) begins with three open questions (Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2015).

Data collection

A mixed-method approach to data collection was used to assess the impact of the QIP process and measure outcomes because the healthcare system is complex and ever-changing, with many interdependencies and a range of variables affecting the project's success. Quantitative data collected for the QIP included the DVT questionnaires, the number of Wells' templates completed on EMIS, and Likert scale questions. The quantitative data collected were analysed into ratio data, which measures variables on a continuous scale, with an equal distance between adjacent values, and classifies data. However, this section is about the qualitative data obtained. Figure 1 details the stakeholder analysis conducted.

PDSA cycle 1

Creating an EMIS template

Based on ideas formed in the initial QIP team meeting, an easy-to-use template was adapted from the Wells' score template (Wells et al, 2003) and embedded into the main multifaceted templates that the MDT uses.

PDSA cycle 2

DVT training session and prompt card

The training was based on the pathophysiology of DVT and national guidance. Aiming for a multimodal approach to learning, the presentation was engaging and interactive, created to educate a diverse team with variable knowledge and skill sets (Mangold et al, 2018). Feedback about the template was collected from the MDT in PDSA 2.

PDSA cycle 3

Team feedback meeting and repeat of the DVT audit

A final meeting was held with the MDT, structured on the Pendleton feedback model (Hardavella et al, 2017); a learner-centred approach was adopted, creating a positive and supportive environment for the participants. The meeting started on a positive note with an acknowledgement of the team's participation. The results of the project were shared, followed by a discussion of the shared first-hand experiences. It led to constructive feedback from staff on the reality of using the Wells' score in practice. This meeting enabled the staff to productively reflect on the conflicting pressures regarding their workloads.

Data analysis

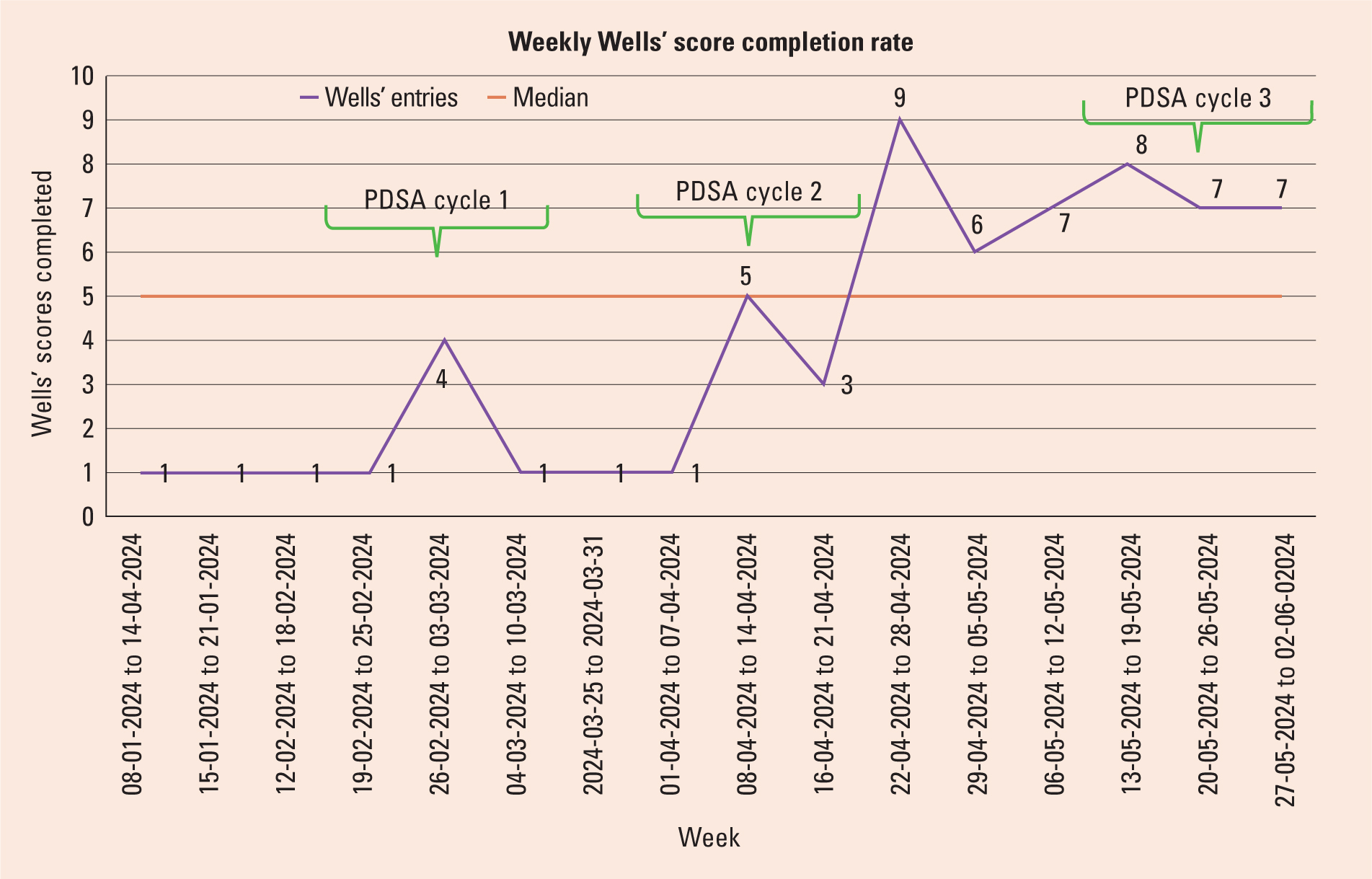

The quantitative data collected from EMIS were analysed into ratio data which measures variables on a continuous scale with an equal distance between adjacent values and a zero point, and ranks and classifies data (Figure 3a). This is significant because it enabled statistical analyses by applying all available mathematical processes (Perla et al, 2011). Using a run chart and the four diagnostic chart criteria, the project's impact was visually represented (Figure 4).

Plotting the median for the anticipated central tendency measure provided more room for differentiation, allowing the authors to examine areas of success or re-evaluation (HQIP, 2015). Ordinal data analysis was useful in evaluating views and opinions that were not captured on the EMIS data.

Findings

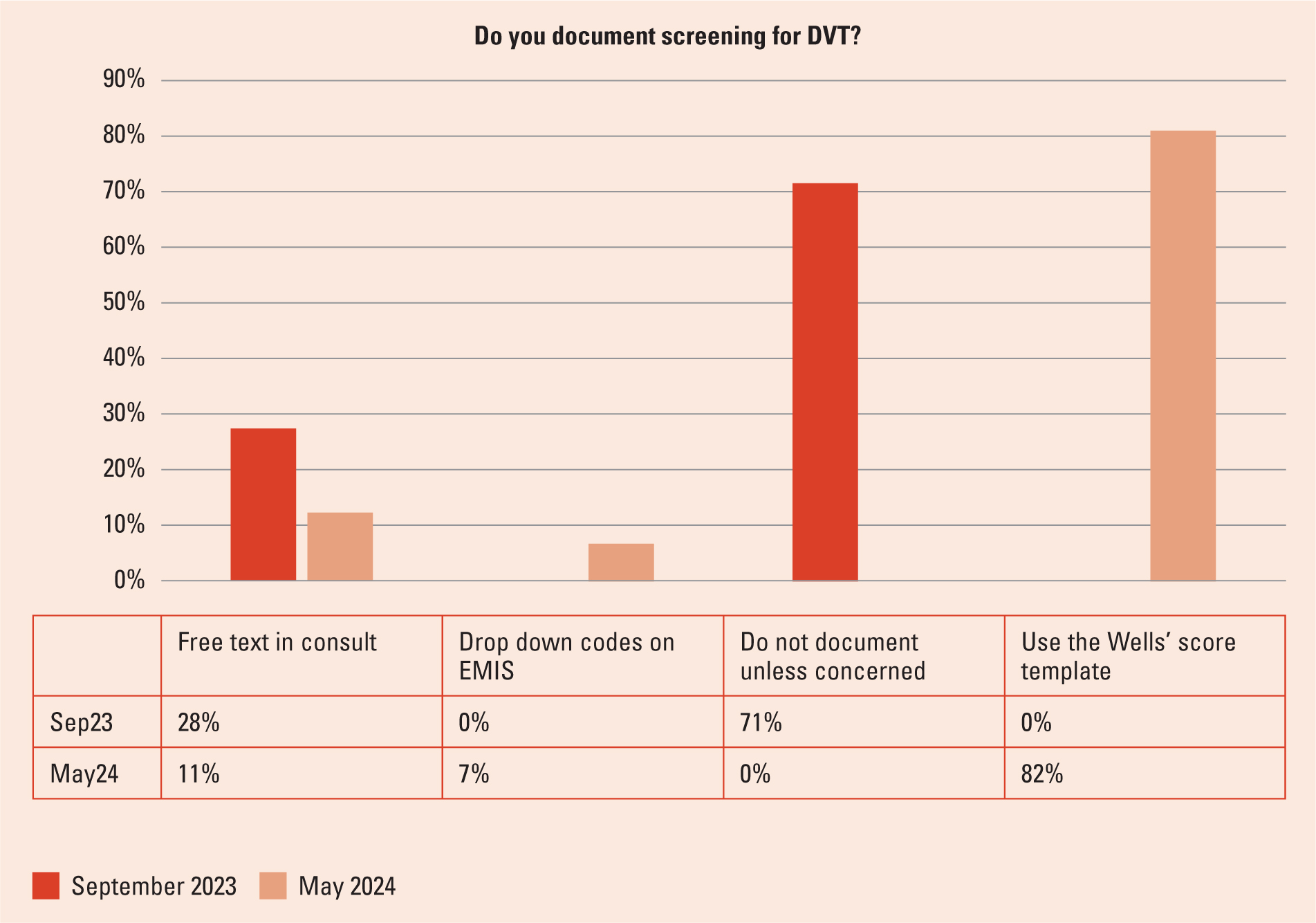

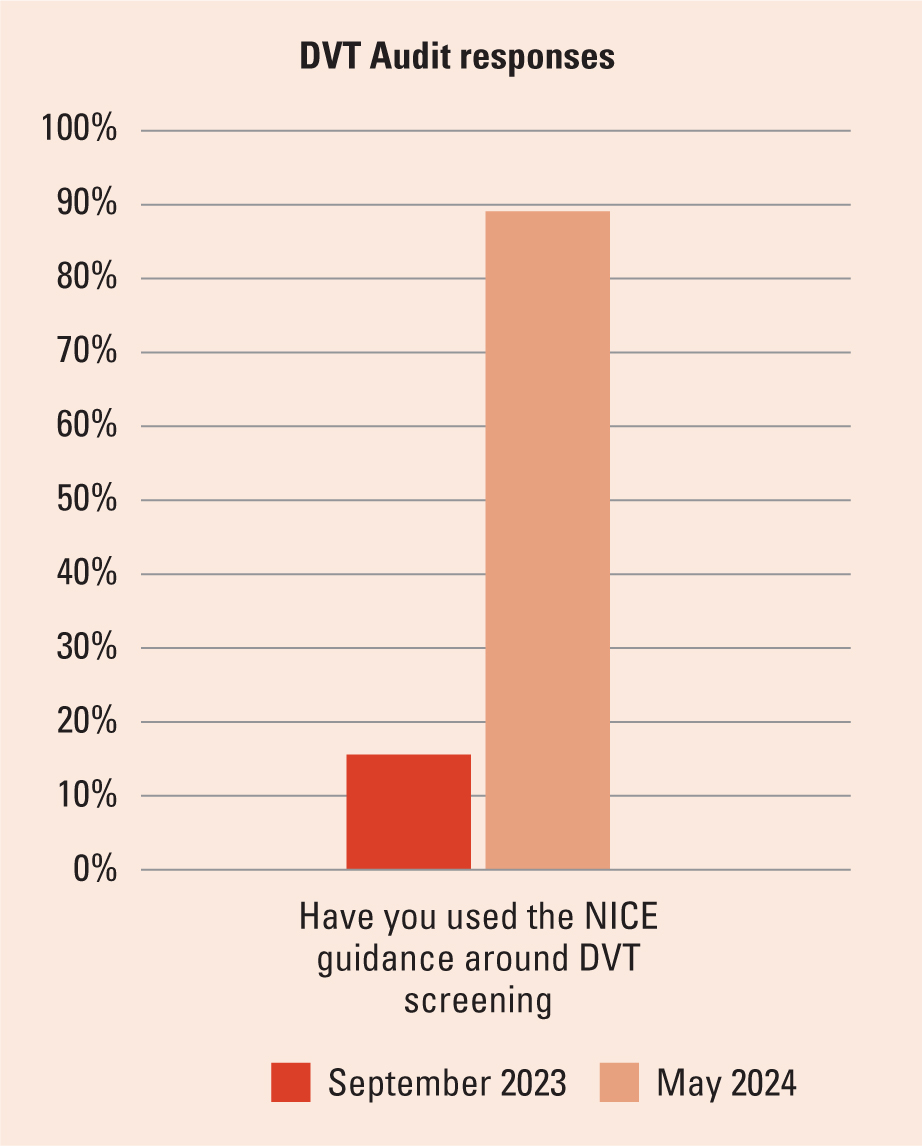

During the concept and preliminary phases of this QIP, baseline data were collected from a staff audit because no data were available on EMIS. The data showed an opportunity for improvement; 100% of the MDTs said they knew what DVT was, but only 57% felt DVT screening was part of their role, which is contradictory to the NHS contract (NHSE, 2023b). The audit also highlighted that 85% did not use NICE guidance (2023) around DVT assessment. A worrying 71% did not document evidence of screening for DVT unless concerned; however, 86% felt a template on EMIS would be beneficial.

Results of each cycle

Process measures for PDSA cycle 1

Once the adapted template was live adapted from the Wells' score template (Wells et al, 2003) (Figure 5), the team's three ACP members trialed it because they were confident about using the Wells' score. The overall feedback was positive in terms of both its ease of use and location. The Lead ACP commented:

‘The Wells' score template is easy to use and serves as a great prompt for documenting in the patient's home on the iPad. It has served as a good reminder that I need to consider DVT while assessing.’

Process measure for PDSA cycle 2

A Likert questionnaire was distributed five days after the training sessions. The overall feedback was positive; 100% of the team felt that the DVT training would enhance patient care. All the participants strongly agreed or agreed that the training session was interesting, interactive and increased their knowledge of DVT; 88% strongly agreed that they now considered DVT during their patient assessments and found the Wells' score template on EMIS helpful.

A total of 94% of the team felt that the DVT training and prompt card were helpful to their role and helped them better understand how to use the Wells' screening tool. However, 12% of the team felt neutral about having a better understanding of NICE guidance (2023), while the rest agreed or strongly agreed.

When asked if they felt confident about implementing the Wells' score in practice, 50% agreed, whereas 32% scored neutral and 18% disagreed. When asked if the Wells' score template was easy to find, 53% agreed, 38% strongly agreed, 7% disagreed and 1% felt less confident. These results were addressed during the last PDSA. In the comments section, one staff member said:

‘The therapy team was struggling to locate Wells' score in their templates.’

This concern was raised with the therapy team, who informed researchers that they used two generic templates, one for standard therapy assessments and the other for crisis. The data team were requested to insert the Wells' template in both templates to avoid confusion in the future.

Process measure for PDSA Cycle 3

The final team meeting aimed to collect both quantitative and qualitative data about the project to see if the outcome measures were achieved. Staff were asked to complete a revised DVT audit and share feedback, which gave context to the quantitative data to aid analysis and identify the project's success and areas of development to build on in the future. The team shared their opinion of each stage of the QIP and shared their experience using the Wells' score in practice; the overall feedback was positive with comments such as:

‘The training was great, very engaging. I really learned a lot, I knew DVT can be caused by poor mobility but not all the other risk factors and it was good to learn how DVT is ruled out. It is even better to know that we just have to escalate to an ACP or senior clinician. Using the Wells' score made the handover so easy because the senior clinicians all know about the Wells' score. The guidance makes it clear as to what steps need to be taken next.’

‘We are busy, but we already assess legs and the Wells' score is simple and clear; it takes no time to fill out.’

Overall outcome measures

The revised DVT audit was shared to assess if the outcome measures had been achieved (Table 1). The DVT audit data showed the project was successful in achieving its aims.

| Do you know what a DVT is? | 100% responded yes |

| Are you aware of the potential harm caused by DVT? | 92% ticked all six options |

| Is screening for DVT a part of your role? | 89% said yes |

| Have any service users in your care had a DVT or pulmonary embolism in the last three months? | 10% said yes |

| Have you used the NICE guidance around DVT screening? | 89% said yes |

| Do you know about the Wells Scoring tool? | 100% said yes |

| Do you document that you have screened for DVT? | 11% free text in consult, 7% use drop down code on EMIS and 0% do not document unless concerned. 82% use the Wells' template |

| Do you feel it will be beneficial to have a small template to document/provide evidence that you have screened for DVT? | 92% said yes |

| Do you feel confident to raise concerns if you think a patient may have a DVT? | 89% said yes |

| Any comments about the DVT project, training, or the Wells' template? |

|

Note: DVT: deep vein thrombosis; Egton Medical Information System (EMIS); National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

The data collected showed a positive increasing trend after PDSA cycle 2. Week 11 had the highest score, which was the week the template was added to an additional location for the therapists. The results showed little variation; however, the project period was only a small window, so further data collection is required to assess sustainability.

Discussion

During the QIP, two clear, specific and realistic targets were proposed, designed to be attainable for a team with a high workload and conflicting pressures. Target one was to increase the use of NICE guidance from 15% to 30%. The second target was to improve screening documentation from 28% to 45%. The QIP exceeded those targets, increasing from 15% to 89% and 28% to 82%, respectively. A contributing factor to this achievement was collaboration with the care community team and their contribution to the design of the interventions and regular feedback during each PDSA cycle. Rowland et al (2018) highlighted that a team's positive dynamic has a pivotal role in a successful QIP, offering ideas based on frontline experience, the demands of their roles and the target service users. In addition to the team's positive dynamic, the training presentation contributed to the project's success and received positive feedback as it was designed to incorporate all learning styles.

The Wells' DVT score has been successfully implemented across several healthcare services, including outpatients and emergency services (Magaña et al, 2011). Multiple studies, including one in a trauma centre, found that using the Wells' score brought positive results: Modi et al (2016) described the Wells' score as a hybrid approach to DVT assessment, with 100% sensitivity of ruling out DVT in those who scored <1 and 90% sensitivity in prediction of DVT with those who scored >2 However, a study by Trihan et al (2021) on using the Wells' score on inpatients found little improvement in DVT identification but rated it a beneficial tool to aid clinical judgment. While the Wells' score template could be ambiguous, practitioners highlighted that its success depends on the clinician's level of experience.

‘I don't feel confident in predicting the possibility of another condition in the patient. I don't have the assessment skills to make that decision.’

Still, the Wells' score has proven beneficial across most studies and remains a valuable tool. Hao et al (2023) introduced age-adjusted D-Dimer in refs list thresholds, in addition to using the Wells' score, and found a higher diagnostic value with a negative predictive value of 93%. Balance measures were set to check if the project affected the reporting of common differential diagnoses, so data were collected on the reporting of cellulitis and oedema on EMIS. While cellulitis reporting did not show any pattern of change, oedema reporting increased after PDSA cycle 2, possibly because it was discussed in training. No consistent patterns of change were identified.

Strengths and limitations

The QIP was set in a time frame of four months, which limited the data collected in testing the longevity of the changes implemented. The trainee ACP had to juggle a high workload and university, and personal demands which affected the number of times they could meet with the team. However, with the guidance of the supervisor, realistic goals and consistent feedback, the trainee ACP was able to effectively plan and deliver the project. The lack of standardised DVT screening before the QIP resulted in the project relying on subjective and self-reported data, which were triangulated with the Wells' template.

Conclusions

The QIP successfully superseded the targets set to improve DVT screening for housebound patients. The findings confirm that collaborative working is effective and provides a solid foundation for future efforts. These will focus on ensuring sustainability and growth, including training for other care communities. There is also an opportunity to conduct further primary research in same-day urgent care by collecting data on community referrals. This can be used to compare the Wells' score and its predictions for patients with DVT, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing hospital admissions.