Nausea, an unpleasant sensation in the stomach, accompanied by a feeling of the need to vomit, and vomiting, the dynamic explosion of gastric contents through the mouth, are different physiologic processes, activating the same neural pathways (Wickham, 2020). Nausea and vomiting (N&V) is often multicausal for patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care, often as a consequence of their primary disease, treatments including anti-cancer therapies, impaired gastric emptying, opioid use, or cranial causes (Leach, 2019). Collis and Mather (2015) and Glare et al (2011) highlight the importance of a comprehensive assessment in determining the cause and likely reversibility of N&V, thereby providing accurate information related to the antiemetic strategy. The antiemetic strategy is based on sound knowledge of the mechanism of N&V, the pathophysiology of this mechanism and the pharmacology of the drugs available, ensuring effective prescription and administration of medication to ameliorate the identified mechanism causing the N&V (Glare et al, 2008). There is recognition that a specific palliative care assessment tool, such as the Pepsi-Cola mnemonic (Gold Standards Framework Centre, 2014) (see Tables 1a and 1b), can complement clinical experience and assessment, directing the assessor to obtain an in-depth history and to identify the palliative care needs and support required of the person receiving care (Faull and Blankley, 2015).

Table 1a. Holistic patient assessment: Pepsi-Cola mnemonic

| Consider | Cue questions | Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P Physical | Physical needs, including:

|

|

|

| E Emotional | Emotional needs, including:

|

|

|

| P Personal | Personal needs, including:

|

|

|

| S Social support | Social care needs, including:

|

|

|

Table 1b. Holistic patient assessment - Pepsi-Cola aide memoire

| Consider | Cue questions | Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Information communic ation | Information and communication needs:

|

|

|

| C Control and autonomy | Level of autonomy needs:

|

|

|

| O Out of hours | Advanced care planning needs:

|

|

|

| L Living with your illness | On-going care needs, including:

|

|

|

| A After care | Bereavement needs, including:

|

|

|

This case study will progress to an in-depth analysis of a community patient's experience of N&V, identifying the likely cause, resulting in the appropriate antiemetic therapy being initiated (Watson et al, 2019).

Assessment

Confidentiality will be maintained throughout this case study with the use of pseudonyms in accordance with the standards set in the Code (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2018).

Peter is a retired carpenter, aged 81 years, who moved to a rural village in 1998 with his wife Rose; they have one daughter, Dawn. Peter has an extensive cardiac history, including a myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension. In June 2015, Peter was diagnosed with a malignant tumour of the urinary bladder, and subsequently diagnosed with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in December of that same year. Peter maintained a good quality of life from this initial cancer diagnosis until late May 2020, when he began to experience intermittent blurred vision and headaches. A Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the head established that Peter had cerebral metastases. Having received five fractions of palliative radiotherapy, significantly improving his symptoms, Peter was discharged home in early July for end-of-life care (EOLC).

As a community staff nurse first meeting Peter the day following his discharge, he was mobilising independently, eating only porridge and drinking regularly; however, he was experiencing persistent nausea, which was relieved for short periods after vomiting. Peter explained that, since feeling nauseated, it had become increasingly difficult to sleep; sitting upright eased the nausea slightly, while being supine exacerbated it; his appetite was significantly reduced, as he ‘never felt like eating’. Peter was opening his bowels daily and still managing to take all oral medication; therefore, no untreated cause of the N&V was identified. Effective management of Peter's N&V was imperative to ensure he could receive EOLC at home, which was his explicit wish.

Aetiology

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2020a) reported that relief of nausea after vomiting suggests the cause could be gastric stasis. Raised intracranial pressure is understood to worsen nausea when a patient has been supine (Walsh et al, 2017; NICE, 2020a). Peter reported that his nausea eased slightly and his appetite marginally improved while he was taking oral dexamethasone in hospital during the course of his radiotherapy. Watson et al (2019) maintained that corticosteroids should be prescribed if N&V occurs as a result of raised intracranial pressure as a result of cerebral oedema or metastases.

The deduction from Peter's description of the occurrence of the N&V was that there were a variety of probable causative factors—including gastric stasis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), ongoing side effects from whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) and raised intracranial pressure as a result of the newly diagnosed cerebral metastases—that the team needed to consider. Walsh et al (2017) asserted that the causes of N&V in advanced cancer can be multifaceted, citing elevated intracranial pressure as a common trigger, while Sinha et al (2016) identified N&V, alongside fatigue and scalp erythema, as short-term side effects of WBRT.

Management

Peter was keen to continue taking oral medications and, therefore, commenced 50 mg of cyclizine, prescribed three times daily. Evidence supports the use of cyclizine as an appropriate antiemetic since it is an antihistamine, H1 receptor antagonist and is commonly used in patients with advanced cancer (Ingleton and Larkin, 2015). In addition, cyclizine obstructs histamine receptors in the vomiting centre, while blocking conduction in the vestibular cerebellar pathway, and is effective for patients where N&V is a result of raised intracranial pressure (Watson et al, 2019; NICE, 2020a; Palliative Care Wales, 2021).

Discussion with Peter's GP resulted in the prescription of 4 mg of oral dexamethasone to be given in two divided doses daily. There is much literature within the palliative care symptom management domain supporting the use of dexamethasone, due to the contributory antiemetic effect it has (Sinha et al, 2016; Ferrel and Paice, 2019; Watson et al, 2019). However, NICE (2020a) maintain that, if intracranial pressure is raised, a dose of 8-16 mg of dexamethasone should be given daily and discontinued after 7 days if no obvious benefit is demonstrated. Peter's GP gave justification for prescribing the lower dose of corticosteroid, stating that the side effects of the high dose could cause additional problems for Peter, including hyperglycaemia and insomnia (Ferrel and Paice, 2019). Peter's GP ensured that the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) omeprazole (20 mg once daily) was prescribed. This PPI is recognised as treatment for the management of GORD, a potential cause of Peter's N&V (NICE, 2017). Furthermore, it is also required for patients at risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects with oral corticosteroids, which includes patients with serious comorbidity, such as advanced cancer (NICE, 2020b).

Peter's family contacted the district nursing (DN) team in mid-July 2020 to report that Peter was feeling increasingly nauseous, had vomited twice during the previous day and was finding oral medication difficult to swallow. Peter's GP spent time discussing the transition into the terminal phase of Peter's illness with Peter and his family. NICE (2020a) identified various signs that indicate a patient is entering the terminal phase, which include reduced mobility, increased fatigue, eating and drinking little or no food or fluid, and having difficulty swallowing oral medication.

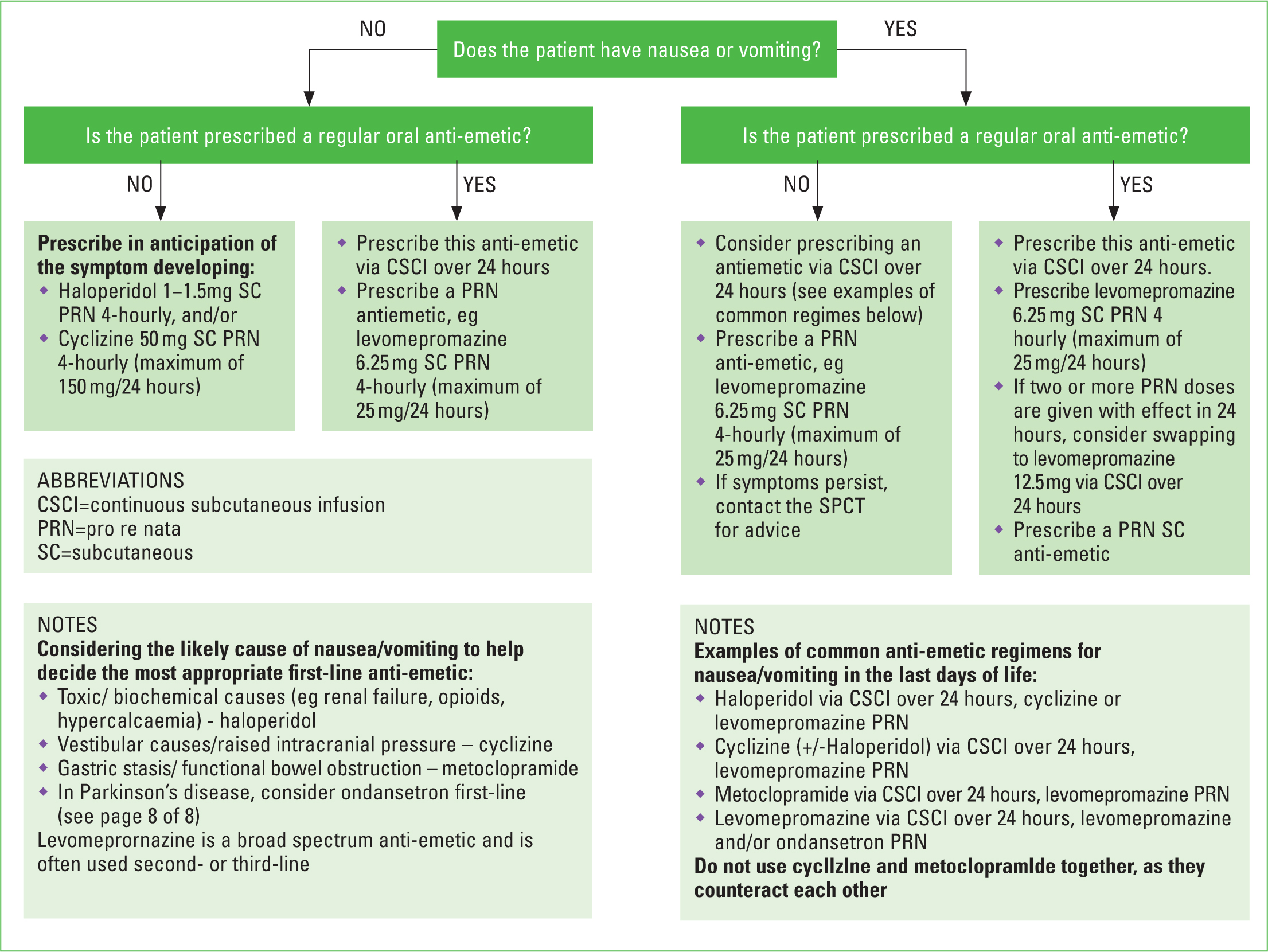

Cyclizine had been effective in managing Peter's N&V; therefore, as endorsed by NICE (2020a) and Palliative Care Wales (2021), the continuation of cyclizine via continuous subcutaneous infusion (CSCI) was prescribed (Dietz et al, 2013). The GP followed the All Wales: Care Decisions for the Last Days of Life—Symptom Control Guidance (Palliative Care Wales, 2021), and prescribed 150 mg of cyclizine via CSCI over 24 hours. Ingleton and Larkin (2015) concluded that continuous antiemetic regimes are increasingly effective, compared with intermittent regimes. Figure 1 illustrates the flow chart produced by Palliative Care Wales (2021).

It was noted at this time by the DN team that contact had not been made with Peter for 8 days since his commencement of oral cyclizine. Peter had a robust support network and his family were able to contact the DNs if required, and he had expressed a desire to live as independently as he was able to, for as long as possible. Therefore, the DN team determined that a phone call to Peter's family 72 hours following the commencement of oral cyclizine would be beneficial to evaluate its effectiveness and identify Peter's ability to continue with oral medication. The inability to swallow oral medication is an indicator for the prescription of a CSCI.

In addition to the CSCI, Peter's GP prescribed pro re nata levomepromazine 6.25 milligrams subcutaneous every 4 hours, with a maximum of 25 milligrams to be given in 24 hours. Levomepromazine is a broad spectrum anti-emetic, considered effective at low doses for N&V with no contraindications for its use in EOLC, providing the dose is carefully titrated (Dickman and Schneider, 2016; Watson et al, 2019). Peter felt the dexamethasone was causing insomnia and not improving his appetite, therefore he agreed with the GP that he would discontinue the corticosteroid. Wittenberg et al (2015) emphasise the need for patient-centred palliative care that facilitates patient autonomy and access to information and choice, which is considered a valuable outcome for patients receiving palliative care, who often feel disempowered. On reflection, Peter may have benefited from further discussion regarding the discontinuation of the dexamethasone, ensuring that he was aware that both the nausea and symptoms associated with raised intracranial pressure could ‘relapse’ (NICE, 2020b). This in-depth discussion did not occur, and it was also difficult to ascertain if Peter's N&V worsened as a result of stopping the dexamethasone.

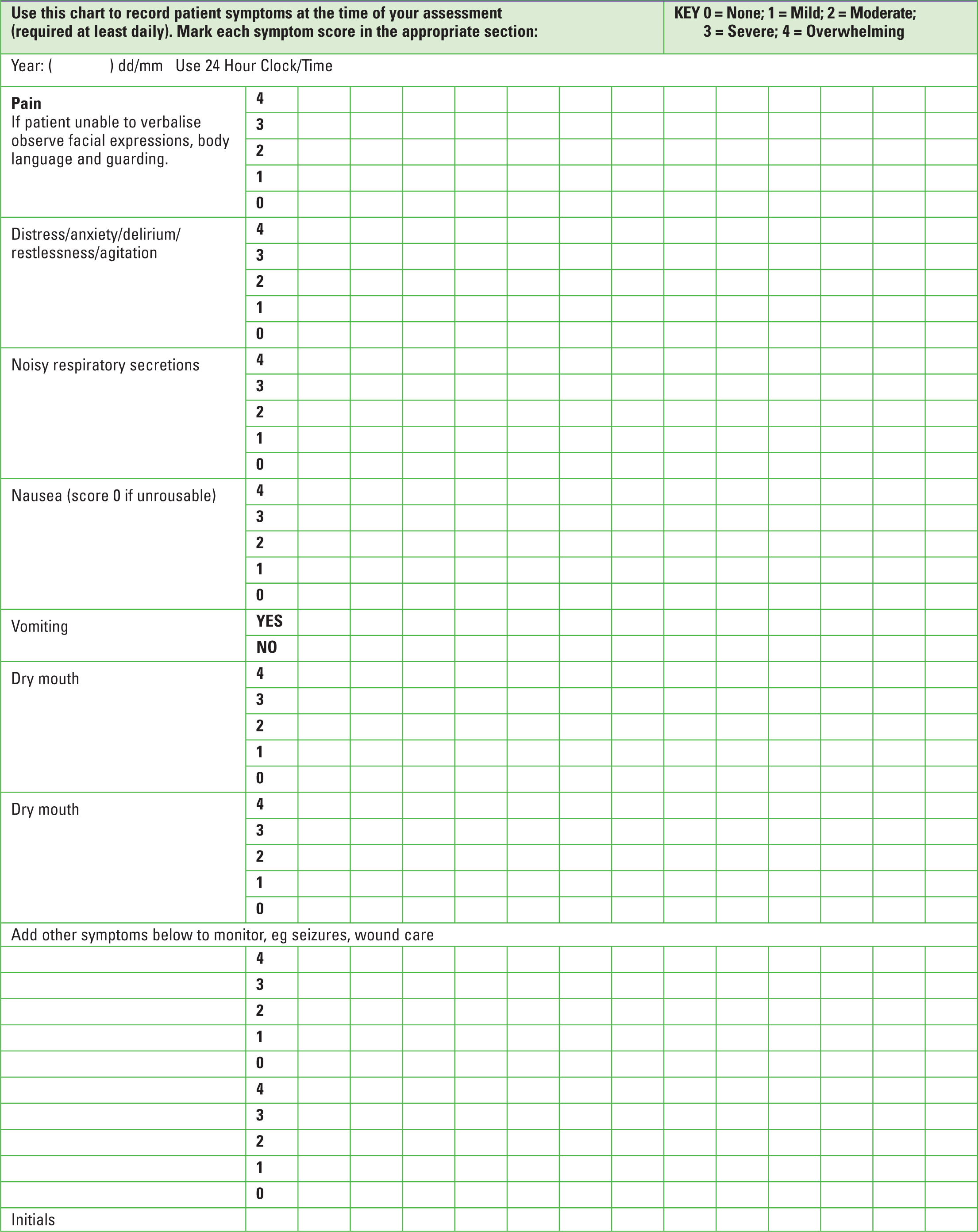

Prior to the DN visit, the day following the prescription of the CSCI of cyclizine, the team were informed that Peter's nausea score had been 4 (Palliative Care Wales, 2021) (Figure 3), and he had vomited overnight and had been given 6.25 mg of levomepromazine subcutaneously. Peter reported that the levomepromazine had worked with good effect, reducing his nausea score to 0. The GP discussed the option to switch to levomepromazine via CSCI with Peter, as it had been beneficial, ensuring Peter was aware of the potential sedative effects. Peter made an informed choice to adjust the CSCI to levomepromazine, as he felt the possible sedative effect would be beneficial in facilitating rest and sleep. Therefore, the cyclizine was discontinued and 12.5 mg of levomepromazine was prescribed via CSCI (Palliative Care Wales, 2021). There is considerable evidence supporting the use of levomepromazine in palliative care, emphasising the effectiveness as a second- or third-line agent, due to the extensive action on receptors involved in emesis (Twycross and Wilcock, 2011; Dietz et al, 2013; Cox et al, 2015; Watson et al, 2019). In addition, Darvill et al (2013) highlighted the stability of levomepromazine with other medications in a syringe driver, alongside the long duration of action, substantiating this common drug choice in palliative care.

The prescription of pro re nata medication is common in palliative care in response to fluctuations in symptom levels. The risks and benefits of regular PRN prescriptions should be considered, particularly for individuals receiving palliative care, as they are susceptible to the adverse effects of medication because of their altered metabolism, organ dysfunction and probable polypharmacy (Russel et al, 2014). The prescription of PRN cyclizine was considered alongside the CSCI, as it had initially been beneficial to Peter. Peter's GP referred to the All Wales Guidance: Care Decisions for Last Days of Life: Symptom Control Guidance (Palliative Care Wales, 2021), which specified PRN levomepromazine or PRN ondansetron alongside a CSCI of levomepromazine. Therefore, PRN levomepromazine (6.25 mg) was prescribed, with a maximum dose of 12.5 mg to be given in 24 hours, ensuring that no more than 25 mg would be administered within 24 hours to prevent unwanted sedation (Twycross and Wilcock, 2011; Palliative Care Wales, 2021). The Palliative Care Guidelines (Back, 2020) emphasise the need to recognise sedation as a potential side effect of levomepromazine at doses greater than 12.5 mg. In addition to sedation, known adverse drug effects from levomepromazine can include postural hypotension, skin irritation, dry mouth, asthenia, and dystonia (Joint Formulary Committee, 2022).

Consideration for non-pharmaceutical measures that could have lessened Peter's nausea were discussed with Peter and his family, including attempts to reduce intense smells within the house, regular oral hygiene and the use of products containing ginger (Ingleton and Larkin, 2015). These non-pharmaceutical suggestions were to be implemented at Peter's request, as there is limited evidence for alternative therapies such as ginger; therefore, compliance with these therapies is variable, frequently based on the patient's own experience and potential symptom relief (Back, 2020; National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2021).

Following the increase of the levomepromazine to 12.5 mg, Peter enjoyed a stable 10 days; however, further functional decline occurred in conjunction with significant cachexia. Collis and Mather (2015) stress the need for daily review of the syringe driver prescription. This examination was undertaken by the DN on each visit as the Care Decisions for the Last Days of Life: Patient Symptom Assessment (Palliative Care Wales, 2021) (Figure 3) was completed. The DN would then report back to the GP to ensure dose or medication alterations were promptly made. On day 11 of the prescription of 12.5 mg levomepromazine via CSCI, Peter had required PRN 6.25 mg levomepromazine during the previous night and there had been further functional decline. The CSCI prescription was increased to 25 mg of levomepromazine; on the following day; Peter reported his nausea had eased to a score of 1 (Palliative Care Wales, 2021) (Figure 2), and he felt the increased dose of levomepromazine had been effective in allowing him to sleep for longer periods. The levomepromazine dose was not altered further, and Peter died 5 days later.

Evaluation

Critical reflection of the management of Peter's N&V indicates that this burdensome symptom was adequately managed. There was sufficient and contemporary evidence supporting the use of cyclizine as the first-line antiemetic; it was also apparent that Peter appreciated the opportunity to commence the cyclizine orally, encouraging his independence and ensuring that he felt empowered. Alteration of the antiemetic to levomepromazine had the desired effect, reducing Peter's N&V score to between 1 and 0.

During the nursing assessment with Peter, the cause for his N&V was deemed multifactorial; Collis and Mather (2015) identify that frequently the aetiology of N&V in patients with advanced cancer cannot be confidently established, due to several possible causes. The systematic critique of the assessment and management of Peter's N&V concluded there were a minimum of four causes of his N&V, with cyclizine selected as the first-line antiemetic aimed at targeting N&V caused by raised intracranial pressure. Because of the nature of Peter's advanced cancer, the N&V became inadequately managed with cyclizine as predicted within the literature; which states that broad-spectrum antiemetics are often required because of the multifactorial aetiology of N&V (Collis and Mather, 2015; Watson et al, 2019). Moreover, Glare et al (2011) identified further risk factors for sufficient N&V management in older adults due to possible impaired renal function and altered hepatic metabolism, which can lead to higher levels of medication absorption, greater susceptibility to adverse effects and increased cerebral sensitivity (Joint Formulary Committee, 2022).

Conclusion

There is compelling evidence supporting the need for careful clinical assessment of the symptoms palliative care patient's experience, particularly for those experiencing the burdensome symptom of N&V. Evidence-based care requires healthcare professionals providing palliative care to evaluate symptoms, understand the emetogenic pathway and clinical pharmacology of available medicines, to target the underlying cause of the N&V and improve medication prescription.

Key points

- Nausea and vomiting (N&V) is a common and debilitating symptom of advanced cancer.

- The aetiology of N&V is multidimensional, requiring thorough assessment and comprehensive management.

- Consistent review of antiemetic regime is essential in reducing symptom burden.

- Continuous subcutaneous infusion of antiemetic is necessary when patients are no longer able to tolerate oral medication.

CPD reflective questions

- What are the potential causes of nausea and vomiting (N&V) for patients receiving palliative care?

- Consider how your knowledge of antiemetic medication can support patients who are experiencing N&V.

- How can related guidance, such as the All Wales Care Decisions for the Last Days of Life guidance, support community nurses providing palliative care?

- Reflect on a patient you have cared for with N&V. What medication and dosages were prescribed? Using the BNF, research these medications to learn about the antiemetic's commonly used in palliative care. Make a list of the antiemetics, including the indication for use, cautions, contraindications, side effects and dosages.