The role of the district nurse (DN) is complex and multifaceted (Queens Nursing Institute (QNI), 2015). They specialise in providing nursing care in a range of community-based settings, managing unpredictable situations using strong leadership skills, coordinating and working collaboratively with a wide array of healthcare professionals and supporting and teaching patients, colleagues, carers and families (QNI, 2015).

A DN is a registered nurse who has undertaken a Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) approved programme to achieve an additional specialist practice qualification in district nursing (SPQDN). They are expected to demonstrate higher levels of judgement and decision-making in clinical practice (NMC, 2019).

The previous standards were published in 2001 (NMC, 2001). Therefore, in 2020, the NMC announced that the standards of proficiency for the specialist practitioner qualification (SPQ) in community nursing were to be updated to reflect current nursing practice and complex patient needs (NMC, 2019; 2020a; 2020b). By reviewing these standards, it was envisaged that it will produce knowledgeable and skilled district nurses who deliver high quality care and can lead and manage teams. To offset the changes in the complexity of the patient population in the community and the age of the previous standards, the QNI produced voluntary standards in 2015, which Higher Education Institutions can follow (QNI, 2015). The new standards of proficiency for community nursing specialist practice qualifications (NMC, 2022) were published on 7 July, 2022. This includes seven platforms that will underpin the curriculum for the SPQDN. These incorporate being an accountable and autonomous practitioner, promoting health and wellbeing, preventing ill health, assessment and care planning, providing and evaluating evidence-based care, leading and supporting teams, leading improvements in the safety and quality of care and co-ordinating care and showing an awareness of the wider determinants of health (NMC, 2022).

A report by the QNI and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) called ‘outstanding models of district nursing’ highlighted that the number of DNs has dropped by 43% in the last 10 years (QNI and RCN, 2019). Furthermore, there is an estimated 9.5% vacancy rate in community nursing in the UK (House of Commons, 2018). Between 2019/2020, there were 761 new students enrolled onto a district nurse specialist practitioner qualification (DNSPQ) programme in the UK. The number of students undertaking a DNSPQ is slowly increasing, but it has been suggested that further investment is needed in this specialist role (QNI, 2020; 2021). Presently, there is apprehension regarding future funding streams of the DNSPQ as it is traditionally run, with a suggested move to an apprenticeship model, which could once again threaten numbers (QNI, 2021).

The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) identifies the district nursing services who provide vital nursing care to patients in their own homes, and in the community, as an integral part of future strategy to boost ‘out of hospital’ care. Furthermore, they have the ability to positively contribute to reducing hospital admissions (Unsworth, 2021). Therefore, an increase in patient demand requires the availability of a skilled workforce to lead this national strategic goal, so an increased investment is required to ensure there are enough highly trained and qualified DNs available. Yet, recent reports appear to suggest the district nursing workforce is an ageing one, with people planning to retire or leave in the near future (Swift and Punshon, 2019). A lack of trained nurses was noted as a factor, which significantly affected the level of patient care in The Francis Report (Francis, 2013). In this instance, it has been suggested that if the shortfall of specially trained nurses in the community is not improved, the vision of bringing more care into people's homes cannot be brought to fruition.

Method

There is a gap in the current literature, which explores the experience of students undertaking the SPQDN. The aim of this study was to explore the feelings, thoughts, experiences and expectations of student DNs at the start of the programme and at the end. It is hoped that this will add to the evidence base to support the requirement for sustained investment in this qualification. An interpretative, phenomenological, qualitative approach was undertaken in order to obtain the data to support the aim of the study. Full ethical approval was obtained through the Liverpool John Moores University ethics board (#19NAH036).

Recruitment

A convenience sample of 10 registered nurses who were seconded from local NHS trusts were used to recruit participants to take part in the study. All students who were enrolled on the specialist practitioner qualification in district nursing starting September 2019 were invited to take part. The co-researcher was the DNSPQ lead at the Higher Education Institute. They verbally advised the students on the nature of the study and gave them a participant information sheet. The focus group would take place 48 hours later and participation was on a voluntary basis.

Participants

All participants in the study were registered nurses working in the community setting and had been seconded from two local NHS trusts to become district nursing students. All participants were female. The ages ranged from 30–47 years. The years of service as a registered nurse ranged from 3–14 years, with a mean of 9.25 years. The years of service in the community ranged from 2.5 years–14 years, with a mean of 6.8 years.

Data collection

The initial data collection (FG1) was collected using an hour-long face-to-face focus group held at the university where students were undertaking the SPQDN programme. The first focus group took place within the first week of study to capture the real and raw emotions when starting the programme. The focus group was conducted within the timetable of the programme to encourage participation. Nine participants attended this group, one student was unable to attend. A second focus group of 7 participants and a one-to-one interview was conducted via Zoom in July 2020, due to restrictions in place due to COVID-19. Two participants had left the programme due to personal reasons and one participant resumed the programme at the mid-point due to returning from maternity leave. The primary researcher facilitated both focus groups. The co-researcher was not involved in any aspect of data collection or analysis in order to minimise participant bias.

Data analysis

The data from FG1 was audio recorded and FG2 was video recorded via Zoom. The researcher transcribed the data from both focus groups. It was appreciated that this was labour intensive; yet, it allowed full emersion into the data to confidently identify themes. Responses were colour coded and emerging themes were identified. All data was anonymised and non-identifiable.

Results

Focus group 1 (FG1): face-to-face

Word cloud on the question ‘Can you sum up in three words how you feel to be finishing the SPQDN’. The bigger the word is, the more times this was said (Figure 1).

Feelings

There were mixed feelings from all participants with regards to starting the course, predominantly ranging from excitement and privilege to apprehension and self-doubt. Two students noted they felt excited as there were only two places funded from the whole of their trust. This was further supported by comments such as they felt the:

‘trust have invested in you’

and being:

‘recognised you have the ability to go on it.’

Half of the participants expressed they were anxious about the academic commitment and workload of the programme. It was voiced that some students had not undertaken any academic work for many years and were questioning their ability to meet deadlines, consistently write to a high standard and to also achieve the grades that they want.

‘I felt quite overwhelmed by it all.’

There was an agreement that participants wanted to feel they could lead a team ‘confidently’ and ‘properly’. There was an expectation that the course would provide them with these enhanced skills. An increased confidence in their leadership skills was a recurrent comment from participants and a feeling that they were equipped to do this, once they held this title. It was noted that they did feel that the title of DN came with added pressure, due to the anticipated expectation of what others would then expect of them, once they had completed the course.

Career aspirations

There was a strong emphasis from the participants in needing the course to progress within community nursing. Participants referred to role bandings frequently and needing a specialist practitioner qualification to progress further than a band 5 or 6 role dependant on trust.

‘If I wanted to move and I still wanted to do the job I am doing, I have to have this.’

However, it was noted that there has been a shift in recruitment, with trusts recruiting to roles that previously required an SPQDN qualification. One participant noted it was due to the low rate of funded places on the SPQDN programme, so they:

‘said you don't have to have the SPQ to be a band 6 as they didn't have enough staff.’

However, as a result of this practice there appeared to be unrest in teams, with regards to task allocations between people doing the same job. However, the difference was whether they held the SPQDN or not. Two participants noted that practitioners who had the SPQDN would take a lighter workload and the justification was that as they hold the qualification, more is expected of them. This caused discontentment as they were employed in the same role.

One participant advised they had left their community nursing post in a trust because they did not fund any SPQDN places and they subsequently joined a trust that did. One participant questioned why the qualification was needed when they felt their clinical assessments were thorough and also had undertook senior positions and:

‘I have managed alright, but you have to have it.’

But they were open to exploring how it may change them as a person, as they had been told by others that it most certainly would, both in their personal and professional life.

‘I want to be like that, I want to be as good as you.’

Feedback from previous district nursing students who the participants had worked alongside noted it positively enhanced career opportunities and helped them to develop additional leadership skills. An increase in confidence and inspirational role modelling behaviour was observed, and reports of past students commenting it:

‘changes the way you think, you look at things differently.’

One participant noted that past students seemed to look at issues from a new strategic approach with another participant noting they look at things from a ‘higher level’. There was a consensus from the group that they felt it was needed to progress further in their career within community nursing, especially in leadership roles. By having the qualification, it was firmly believed that it would lead to greater career opportunities. However, half the participants commented that retention post-course was an issue and SPQDN students had left the trust after the secondment opportunity.

The role and title of the district nurse

The role of the DN did generate a rich discussion ranging from role identity to the increasing complexity of patients that the DN supports. It was noted that the complexity of patient care and the type of care undertaken in the community has increased, therefore the skills of a DN must also grow. There were comments made by participants, such as wanting to be ‘highly skilled’ and undertaking learning on the SPQDN programme to equip themselves with additional skills to examine, assess, diagnose and prescribe.

‘We are draining ascites off people's abdomens, you know these things weren't done in the community, now they are.’

There were multiple comments about how these additional skills would directly improve patient care. Skills such as prescribing medication for palliative patients and those who require antibiotics, would enable them to provide holistic care and reduce the need to refer on. Thus, this would have a positive impact on general practitioner workloads, for example, and reduce patient wait times. Furthermore, the additional enhanced leadership skills and a confidence in their ability to lead teams was highlighted as an anticipated benefit of the course.

‘It will be amazing to go back and say: yes I can go and do them end of life drugs for that patient.’

There was a mixture of opinion with regards to only using the title of the DN if the person holds the SPQDN qualification. There was an appreciation that it was a familiar term to patients and that they most likely would not know that a postgraduate qualification was required for this term.

‘if you ask a patient they will say the DN is coming out, they don't say the community care practitioner.’

One participant offered the idea of a visual indicator, so it would be clear who held the SPQDN qualification. Two participants voiced that they had been reprimanded by other staff members when calling themselves a DN to patients on the phone and this was due to them not knowing about needing the SPQDN qualification to use this term. There was a sense of respect that goes alongside achieving the title of DN and this was a reason as to why use of the title should be limited to those who have undertaken the additional training. Contrastingly, two participants also noted that if the nurse was working to a high and professional standard and providing patient-centred care, they did not mind if they referred to themselves as a DN.

‘I will say it doesn't bother me, but then again, I've not got the qualification, so maybe it will when I have it.’

Focus Group 2 (FG2) and a 1-1 interview: virtual call

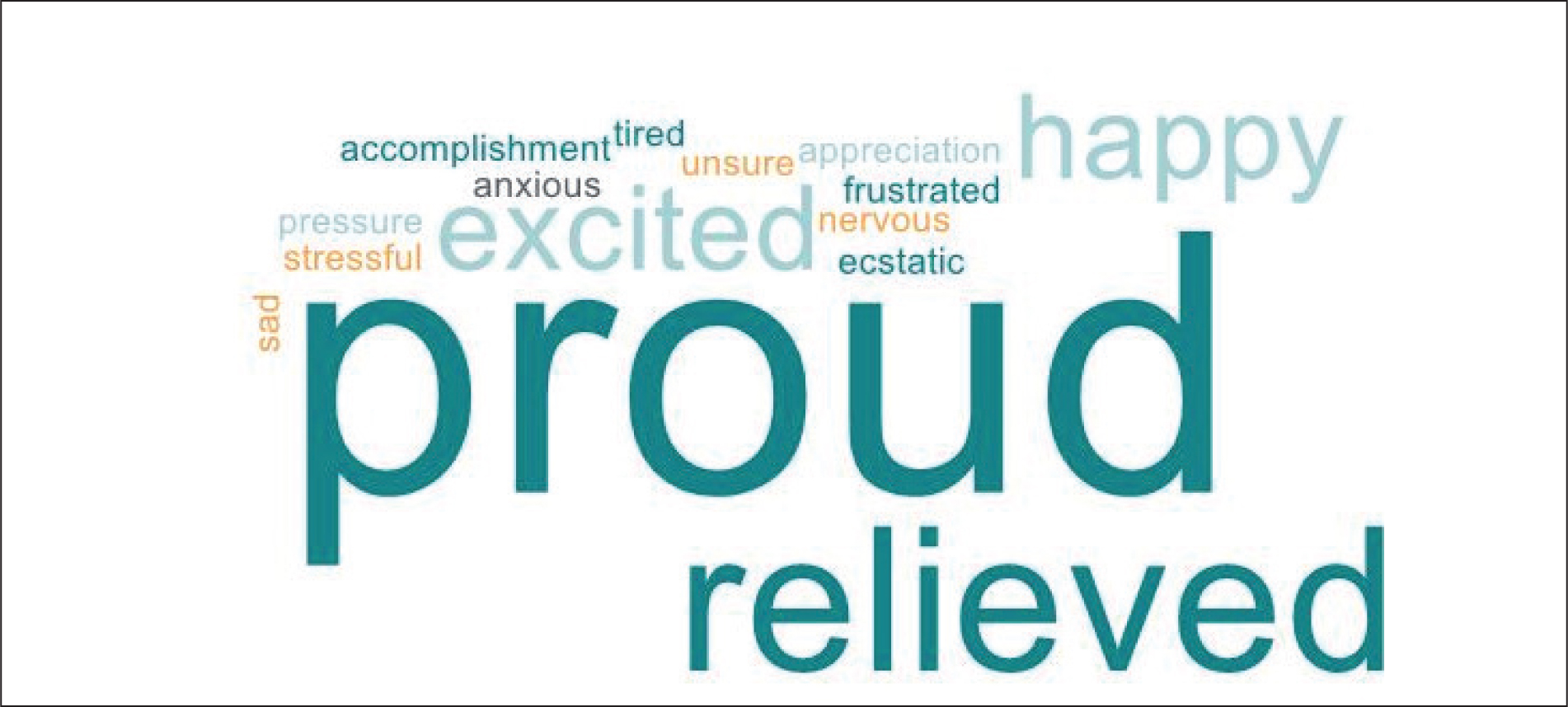

Word cloud on the question ‘Can you sum up in three words how you are feel to be finishing the SPQDN’. The bigger the word is, the more times this was said (Figure 2).

Feelings

There was an overwhelming response from participants that they felt proud of their achievement with regards to completing the SPQDN. There was also feelings of relief, accomplishment, excitement and apprehension. Participants were reflective about what they had achieved including moments of self-doubt to then becoming self-assured as the course progressed.

‘So proud of myself that I have actually done it because I didn't think I ever could, nervous and excited to see where I will be going next’

There was a sense that the course had instilled increased confidence in the majority of participants. Several participants referred to being able to ‘speak up’ and challenge practice when needed. This seemed to derive from an increase in knowledge and viewing things from an enhanced operational and managerial approach.

‘I have grown so much as a person, I have gained so much more confidence.’

Contrastingly, two participants identified that they felt an increase in self-doubt due to enhanced self-reflection and awareness. There was worry expressed regarding the level of support after the course had ended and also the level of expectation from them, now that they had achieved the qualification. However, this was also caveated with the appreciation that these were normal feelings due to the current unknown status of what the future may hold.

It was clear that some participants felt uncertain as to what this meant with regards to career opportunities and future roles, which require the SPQDN. Five participants noted that they felt unsure about which location they would go back to work in, now that they had completed the course, and questioned if there would be any job opportunities available to progress in a senior role, and needing and wanting:

‘to get my teeth into something now and I want to be able to have my own team.’

There was a clear sense of pride and achievement in relation to completing the academic element of the programme, as this was a known worry in the beginning. Participants noted their confidence grew when they received their marks back for their work and an important aspect of succeeding was ‘being organised’. However, three participants were relieved it was over, noting it to be stressful, tiring and intense.

‘I have actually learnt a lot about myself, that if I put my mind to something I can do it.’

Two participants felt honoured to hold the title of DN. However, the rest of the group felt there was always going to be confusion with regards to using the title for all nurses who work in the community setting, due to the term being used freely by patients and other staff members.

Future practice

Participants appreciated having the time to increase their theoretical knowledge through reading and appraising research, in order to ‘keep myself up to date’. The additional prescribing and clinical assessment skills were viewed as enhancing their ability to be autonomous practitioners and gaining the right skills to care for complex patients. For example, participants appreciated the value of being able to prescribe medications as they felt this would enhance the care they could provide. This was particularly true with regards to prescribing palliative medications for patients.

One participant utilised the time to share a skill with the team where they were placed. They identified fellow nurses who felt apprehensive with regards to verification of death, yet the SPQDN student felt confident as they had frequently undertaken this skill in a previous job. Therefore, they allowed colleagues to shadow them to enhance their confidence and ability, which had a positive impact on families, as it meant they did not have to wait for a doctor to attend to verify the death.

‘I said do you know how much of an impact it makes on the family though.’

Being able to shadow other services to increase knowledge and partnership working due to supernumerary student status, was noted as a benefit by the majority of participants. Services such as palliative care, social inclusion, continuing healthcare and community matrons were all examples given of services that were visited. There was an appreciation that being able to observe and spend time with these services enhanced their leadership and partnership working ability. Half of the participants said they had spent time working with senior managers and had the opportunity to be involved in processes such as patient safety meetings and root cause analysis investigations. This was seen as a ‘really positive learning experience’, with new work connections made and an increase in knowledge from a strategic point of view. There was an overwhelming consensus that they had grown as a practitioner by being able to take the time to read, observe, think and act.

Discussion

The participants had a wealth of nursing experience and specifically community nursing experience. It was apparent that for many of the participants, their confidence had increased and they felt a sense of pride and accomplishment at the end of the course. It was also evident this qualification was viewed as a key component to future roles in their career, at a senior level. These feelings are echoed by participants in a study by the QNI regarding the value of the DNSPQ. The top three benefits found upon completion of the course was confidence with professional development, job satisfaction with career development and pride in their achievement (QNI, 2015).

There was an appreciation that care in the community is increasingly complex and the acuity of patients has increased. This point is supported by the current literature (Bliss and Dickson, 2016, Green, 2016). It is imperative that the DN is assertive and demonstrates strong leadership skills, in order to successfully run and manage this busy and complex service (Green, 2016). It was seen that the majority of district nursing students in this study, had demonstrated verbal self-reported increases in confidence and their leadership skills. This concurs with the findings of Green (2016), who also found an increase in assertiveness via a questionnaire of district nursing students as the course progressed. Assertiveness and leadership skills are vital traits in a DN in order to lead and guide a busy community team (Thirtle, 2021).

There was a notable air of apprehension combined with excitement from the participants with regards to starting an academic programme. It was identified that some students were worried about their ability to undertake academic work due to self-doubt and the length of time out of education. It is to be appreciated that post-graduate students on the SPQDN programme may initially experience an element of transitioning where they move from registrant to student and this can also increase attrition rates. This is due to the balancing of commitments outside of the programme combined with the competing demands of the course (Thirtle, 2021). Participants noted they role modelled themselves on previous DNSPQ students as they could see a marked change in their behaviour and mindset after completion of the course. Bliss and Dickson (2016) notes students found the course ‘transformational’. However, it is to be appreciated that the SPQDN programme has been described as ‘intense’ (NMC, 2019, p17), due to the nature of undertaking both clinical and academic assessments. Yet, positively at the end of the programme, students in this study felt proud of all they had achieved, but were also looking forward to some downtime after such a busy 12 months.

Domain three of the QNI voluntary standards (QNI, 2015) is the ‘facilitation of learning’. This was identified in this study when a participant educated and increased knowledge of fellow colleagues regarding the verification of death, in order to provide seamless, excellent patient care. District nursing teams are intrinsic to palliative care provision in the community and a great deal of time is spent caring for patients and supporting their families who have palliative care needs, supporting them to pass away at home, if this is what they wished for (Maybin et al, 2016). Therefore, it is suggested the role of the DN in the nurse-led verification of death process undoubtedly should be embedded within their skill set in order to provide timely, compassionate and continued care (Hospice UK, 2020; Ormandy-Brooks, 2020). However, it is noted that there is an increase in the number and complexity of caseloads, which impede the ability of staff who are able to attend training courses (Thirtle, 2021). It is known that education and training is deferred if teams are short-staffed or extremely busy (Swift and Punshon, 2019). Furthermore, investment in continued professional development has been drastically reduced over the last 5 years (Buchan et al, 2019). Therefore, the benefit of having a highly trained and competent practitioner in a student role in this instance, seemed beneficial to provide that training onsite. Given the aforementioned benefits of nurse-led verification of death, it has been suggested that this should be included in future national undergraduate nursing curriculum (Laverty et al, 2019).

In order to support and educate the SPQDN students of the future, appropriate educators are needed. Ashworth (2020) and Swift and Punshon (2019) suggest that the cycle of education will develop further when previous students become educators, impart their knowledge to help develop future generations of DNs. However, considering that the number of people who hold a SPQDN qualification has reduced, combined with an aging workforce, this may prove to be a potential problematic goal unless investment is increased (Carlin and Chesters, 2019; Swift and Punshon, 2019). Furthermore, 46% of 2858 respondents in a national survey identified that they will retire or leave in the next 6 years (Punshon and Swift, 2019), thus indicating succession planning is imperative in order to educate and support the DN leaders of the future.

The NMC (2019) conducted a nationwide evaluation of the SPQ standards, whereby 291 individuals and 38 approved education institutions gave their views. One of the most common reasons cited as a motivation for doing the SPQDN course was clearly career progression. This finding concurs with those from participants in this study. It was identified that the SPQDN qualification is required when applying for jobs with increased responsibility and promotion. However, participants in this study noted that nurses were now undertaking roles that historically required a SPQDN qualification and this was causing unrest, due to the different identities practitioners held within the same role. Carlin and Chesters (2019) also highlight this and the potential to reduce the need for the SPQDN qualifications and devalue the role and title of the DN. Nonetheless, staff who do not hold the SPQDN have also been promoted to leadership positions (Longstaffe, 2013).

The QNI (2013) conducted a survey answered by 1035 nurses; it also identified that there was confusion regarding appropriate job titles between healthcare professionals, with a range of roles being labelled as a DN. There was a sense that the title should not be lost and should be protected, and also restricted to be used by those with the SPQDN qualification. However, it was recognised that the public will continue to use the term DN for those in many different roles, as it is a term that is familiar to them. Swift and Punshon (2019) identified a lack of consistency in relation to job titles such as the DN, which only serves to cause confusion to the public, organisations and commissioners. Therefore, it is suggested that job roles and titles should be clear and streamlined to reduce such confusion and promote role identities.

Participants noted they had gained additional skills, which would have a direct positive impact on patient care, such as the additional prescribing and clinical examination skills. Including advanced practice skills within SPQDN programmes will evolve and shape the role of the DN, who will be able to care for complex patients in a holistic and skilled manner (NMC, 2019; Ashworth, 2020). Furthermore, by having an advanced and skilled practitioner reviewing patients in their own homes provides the added benefit of avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions, which will contribute to a reduced financial burden on the NHS (Pellet, 2015). There has been recognition, and now an expectation, that a district nursing service, which often works 24 hours a day, is able to significantly contribute to reducing unnecessary hospital admission and this has been included in contractual obligations with commissioners (QNI, 2019). District nursing is the service that works mostly behind closed doors; there is often a lack of appreciation regarding the complexity of care that is provided in the community (Swift and Punshon, 2019). The participants recognised that they were providing highly complex care to patients in their own homes, which historically was not undertaken in a community setting. This is echoed by the findings of Maybin et al (2016).

Limitations

The primary researcher of this study has experienced the programme from a personal and professional standpoint, as they hold the DNSPQ qualification and have taught previous cohorts. However, the researcher did not directly know any of the participants in this study and did not advise them of their qualification. The researcher attempted to remain as reflective as possible throughout the process to ensure they did not lead or guide the participants. The co-researcher was the programme leader of the DNSPQ, but was not involved in any of the data collection and analysis process, and all data was anonymised prior to them proof reading this study.

The students derived from two different community health trusts and were all female, enrolled at one higher education institute in the north-west of England. Therefore, the transferability of this study may be limited. It is suggested that this study be replicated in a different part of the country to ascertain if findings are similar. However, this study does concur with current research findings from a range of sources, thus demonstrating an element of validity.

Conclusion

The modern day DN is a highly skilled practitioner with excellent leadership abilities. In order to achieve the strategic vision of bringing more care into people's homes, as opposed to hospitals, more DNs need to be trained. This is due to an ageing workforce and a lack of investment in the SPQDN programme. This study has shown that undertaking the SPQDN has been transformational for the participants and in turn, this will have an impact on the care they can provide to patients.

Key points

- A district nurse (DN) is a highly skilled practitioner who has undergone additional post-registration training in order to hold this title

- A student DN has the ability to educate and support others due to their experience and increased knowledge, whilst completing the specialist practitioner qualification in district nursing (SPQDN)

- The SPQDN programme is demanding, time consuming and can be overwhelming. Yet, the end result can be transformational for all those who achieve this qualification.

- The DN workforce is an ageing one, with many planning to retire or leave. DNs are integral to achieving the strategic vision of bringing care closer to home.

CPD reflective questions

- Are you a qualified district nurse (DN)? What advanced skills do you possess, which allows you to care for an ever-increasing complex population of patients in the community setting?

- Does your employer support a secondment to allow registered nurses to undertake the SPQDN? If not, how can you demonstrate the role of the DN is imperative within your trust to support high quality care for patients?

- Are you, or have you been a SPQDN student? How did you feel at the start of the experience and how did you feel on completion?

- Do you think the title ‘DN’ should be used exclusively by those who hold the DNSPQ?