Many eye diseases are likely to affect the visual pathway and in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) this involves the neurosensory retina. AMD is a degenerative eye disease that causes loss of central vision. There are two main types of AMD—wet and dry. AMD causes painless loss of vision and predominantly affects older people, although other age groups may develop macular degeneration (MD). Visual impairment can have negative consequences on a person's health and wellbeing. Ageing and the ageing population are inevitably linked to age-related eye disorders and the likelihood of visual impairment (WHO, 2023). Current data estimates that visual impairment affects 2.2 billion people across the world (WHO, 2019), and AMD is one of the leading global causes of visual impairment (Burton et al, 2021).

Anatomy and physiology

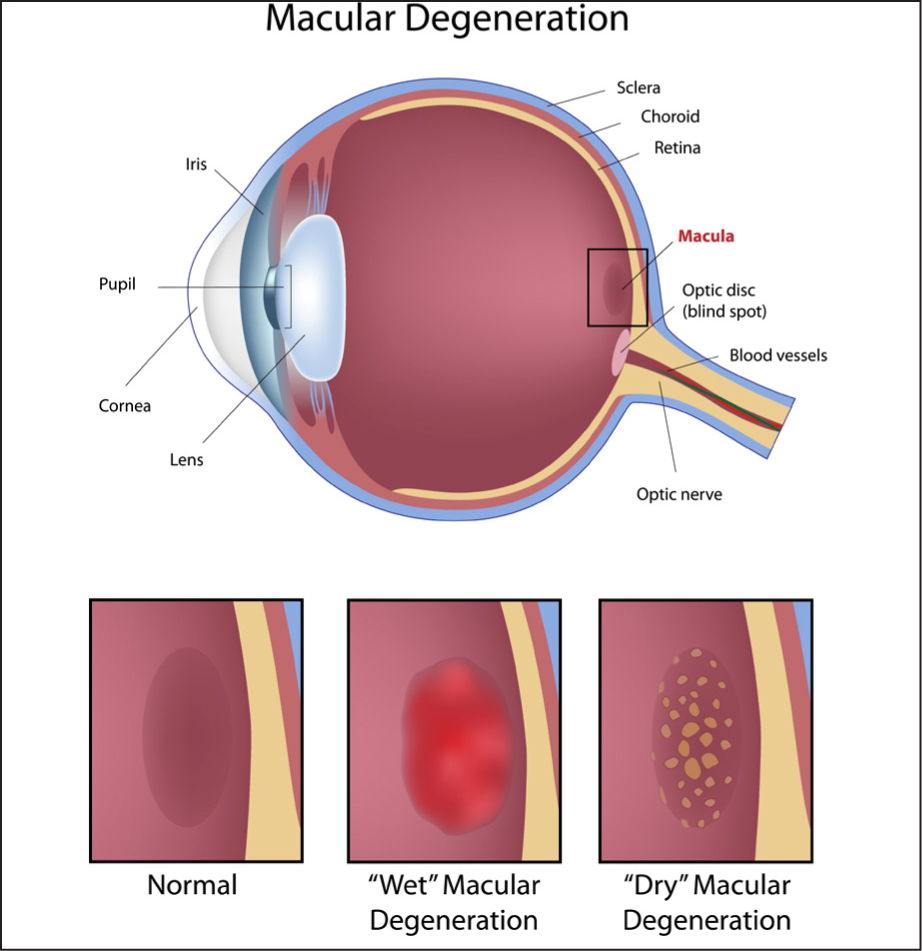

The literature provides consensus on the structure and function of the anatomy and physiology related to AMD (Batterbury and Murphy, 2018; Kanski, 2019). The relationship between the normal anatomy of the eye and pathological changes that occur in some diseases such as AMD, has inevitable consequences on vision. The physiological function of the eye is to convert light from images into electrical impulses, which are then interpreted by the brain as vision. The retina—the inner transparent layer of the eye—is a neurosensory layer. Photoreceptors present in the retina, specifically on the macular, known as rods and cones, are essential in this process. The macula is an area on the retina that facilitates central vision. The fovea, located at the centre of the macula—this is the part of the eye. Its adjective is macular eg macular degeneration. This author confuses the two oftenr, is responsible for detailed vision. Macular rods and cones are more concentrated on the macular responsible for colour and acute central vision. Rods are also present throughout the retina, mostly in the peripheral retina and aid perception of movement and facilitate vision in low light conditions.

There are two main categories of macular degeneration: dry and wet (Figure 1), and these are associated with the pathological changes that occur at the back of the eye. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2018) classifies AMD according to the extent of pathology and AMD-related changes—Drusen, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) degeneration, neovascularisation, atrophy, scarring and visual loss.

Dry age-related macular degeneration

Dry AMD is also known as geographic atrophy (GA). Dry AMD concerns the degeneration of specific areas of the retina, such as the photoreceptors. Drusen, which are extracellular lipids and proteins, develop under the macular and destroy the photoreceptors. GA can develop to cover larger areas of the retina, causing loss of central vision and there are currently no treatment options (NICE, 2018; Fleckenstein et al, 2021). However, it is possible for patients with dry AMD to also develop wet AMD (Fernandes et al, 2022).). Consequently, it is important to promote eye health in this group of patients. In this regard, NHS England's Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) programme provides annual eye assessment and lifestyle advice for this patient group (NHS England, 2023)

Wet age-related macular degeneration

Wet AMD is also known as exudative or neovascular wet macular degeneration, reflecting the growth of new blood vessels (Hobbs and Pierce, 2023).

The pathophysiology of wet AMD (wAMD) is widely acknowledged to be multifactorial, complex and not fully understood (Fleckenstein et al, 2021; Hobbs and Pierce, 2023). It is generally thought that a build-up of a protein vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) precipitates angiogenesis—the growth of new vessels (neovascularisation)—resulting in tissue hypoxia (Tan et al, 2022). The main features, noted on examination of the back of the eye, are the build-up of hard extracellular deposits (Drusen) which degenerate the photoreceptors and neighbouring retinal tissue (Fleckenstein et al 2021; Hobbs and Pierce, 2023). As neovascularisation extends, these new weak blood vessels break and haemorrhage, causing further visual loss or distortion of existing vision (Fleckenstein et al, 2021; Hobbs and Pierce, 2023).

Patient assessment and diagnosis

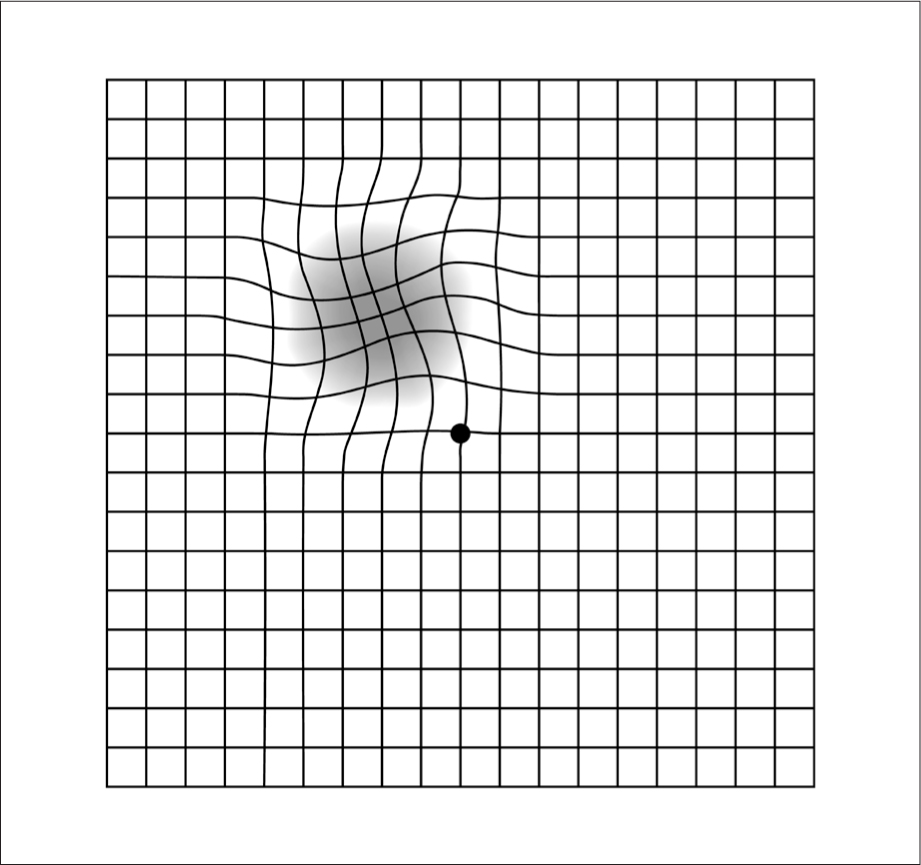

AMD is diagnosed according to a combination of the symptoms reported by the patient and technological assessments of their eye. Patients may experience subtle changes in their vision, and/or notice their central vision to be distorted or blurred (Hobbs and Pierce, 2023) (Figure 2). Some patients may not have symptoms and it is often a routine eye test at the opticians where the condition is first noticed. This raises the importance of regular eye tests and supporting access to eye tests. If a person is unable to attend outside the home, community optometrists can perform eye tests in the patient's own home. This highlights the importance of regular eye tests as part of eye health promotion and education for individuals and the population as a whole.

Patients who do present with signs and symptoms of visual loss and/or visual distortion can be expected to undergo further assessments to confirm the AMD diagnosis and develop a treatment plan. Depending on clinical indications, fluorescein angiography may be indicated. Fluorescein angiography is a procedure where a yellow-coloured dye is inserted into the patient's vein and photographs are taken of the fundus to determine any leakage from the retinal veins (NICE, 2018; Hobbs and Pierce, 2023). Another test is known as optical coherence tomography (OCT). This is a scan showing detailed images of the retina. It is often used to confirm an AMD diagnosis and monitor the progress of AMD and/or the response to treatment (NICE, 2018).

Risk factors associated with age-related macular degeneration

Age is strongly associated with MD. However, other factors that can predispose or exacerbate the progression of the condition. The list below establishes those risk factors that are now understood as being linked to AMD (NICE, 2018; Chakravarthy, 2020; Lombardo et al, 2022):

- Age

- Genetic predisposition

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolaemia

- Low intake of fish, vegetables, fruit (omega 3 and 6, vitamins, carotenoid and minerals)

- High-fat diet

- Lack of exercise.

Box 1.Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) classifications

- Normal eyes

- Early AMD

- Late AMD

- Late AMD (wet active)

- Late AMD (dry) geographic atrophy

- Late AMD (wet inactive)

In terms of risk factors, nurses must use patient contact opportunities to educate and support them in making lifestyle choices. What is also interesting to note is that AMD risk factors are also similar to other conditions such as those underpinning cardiovascular health; yet the general public may not make such links to AMD. One example of modifiable behaviour is smoking. Standardised cigarette packets were introduced with the aim of increasing public awareness of links between AMD and smoking (UK Government, 2014). As it is illustrated on cigarette packs, this has gone some way to educating smokers about the correlation between the two. Smoking cessation options should be individualised to the patient and they should be supported in their endeavours as a long-term nursing care intervention.

There is emerging evidence indicating the potential of high-dose vitamins C, E beta carotene and zinc supplements to limit the advancement of AMD in deterioration and further loss of vision in non-smokers over 55 years of age (Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) Research Group, 2001; Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research Group, 2013). Findings from the studies supported these diet supplements but NICE (2018) has held back from recommending these supplements until additional studies have established clear benefits. Caution is noted concerning beta carotene because of potential increased incidence of lung cancer in former smokers (AREDS2, 2013).

Interventions for patient care

There is currently only treatment for wAMD. The pharmacological interventions for late wAMD, aim to counteract VEGF and growth of new blood vessels. AntiVeg is the umbrella term for the drugs and these are administered as an intravitreal injection. The drug is injected directly into the back of the eye. As it is the first line of treatment for advanced AMD, it is imperative that it is started promptly to prevent any further development of neovascularisation and subsequent damage to the macula and surrounding retina. To that effect, the GIRFT (NHS England, 2023) pathway advises an urgent hospital referral (one day from when a patient is seen by a community health professional such as optometrist), with the first injection to commence within 2 weeks.

Prior to the first injection, a treatment and monitoring plan will be devised and discussed with the patient, the family and carers. NICE (2018) recommends a ‘loading dose’ of AntiVeg followed by 3 or more monthly injections as per individual needs of the patient. Data from the 2023 National Audit of AMD (Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOPh), 2023) indicated that the most frequently prescribed and administered intravitreal treatment (IVT) drugs are Aflibercept (Eyelea), Ranibizumab (Lucentis) and less often, Bevacizumab (Avastin) and brolucizumab (Beovu). The national audit (RCOPh, 2023) found that regular IVT over 12 months was significant in avoiding further deterioration of vision. Some patients also reported improvement in their vision over that same period.

Patients can expect to have their treatment undertaken as an outpatient, and, in response to increased numbers of patients requiring treatment, most likely to be administered by an ophthalmic nurse, optometrist or orthoptist (Greenwood et al, 2021). Recent data suggest that ophthalmic nurses are the profession most likely to administer IVT (RCOPh, 2023) and can therefore, apply their knowledge and expertise to patient-centred holistic care (Greenwood et al, 2021).

Shared decision-making and a person-centred approach is essential. Patients should be fully informed about their treatment and this is considered to improve patient outcomes (Scheffer et al, 2022). However, shared decision-making relies on good communication skills and taking time to discuss all aspects of treatment with the patient, their family and carers. It is also important to recognise that the information provided is person-centred and relevant to the person's language, vision and educational ability. Patients can also be directed to get support from charities such as the Macular Society and the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). Accessible material and telephone helplines offered by such charities provide invaluable advice to support patients' knowledge and decisions pertaining to their condition.

One potential side effect of IVT is raised intraocular pressure (IOP, which can be characterised by pain, nausea, vomiting), but this tends to resolve in the first 10 minutes post-injection (LoBue et al, 2023). IVT complications are rare, but inflammation or endopthalmitis (infection) are potential post-IVT events, and patients need prompt treatment via their ophthalmic healthcare team (RCOPh, 2023).

Supporting patients through minor changes in vision

The community nurse can support patients in monitoring their vision and help them to seek specialist advice. This is important for patients, regardless of the type or treatment phase of AMD. Therefore, any deterioration such as changes in vision or side effects of IVT can be detected and advice sought from an ophthalmic healthcare professional or GP. NICE emphasises the importance of supporting patients to regularly assess their vision, particularly if they are unable to do this themselves.

Self-assessment of vision is advised in respect of the following observations (NICE, 2018). Community nurses can help patients assess any changes, such as:

- Blurring or grey patch in their vision

- Straight lines appearing distorted

- Objects appearing smaller than normal.

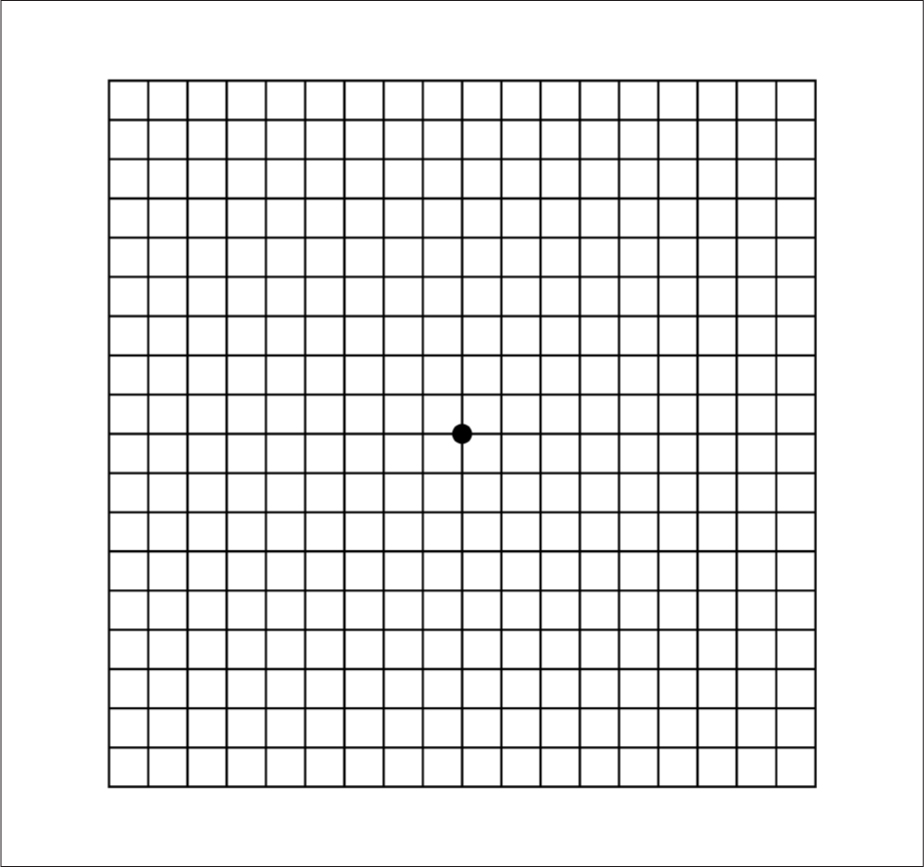

Changes in vision can also be assessed by means of an Amsler grid. Tripathy and Salini (2023) explain the Amsler as a square of horizontal and vertical lines (10 cm x 10 cm). They go on to advise that patients are taught to hold the grid around 33 cm in front of their eyes. While the Amsler grid does not replace an assessment by the ophthalmic team, it is a useful aid to indicate or monitor potential changes to central vision (Figures 3 and 4).

Age-related macular degeneration and its real-world effects for the patient

The impact of AMD on the life of the patient, family and carers cannot be underestimated. AMD has been referred to as ‘a great physical and psychological burden for patients’ (Thier and Holmberg, 2022). Apart from the diagnosis of AMD, its potential and actual vision loss, attending IVT clinics for regular IVT injections was reported to be an additional burden (Thier and Holmberg, 2022).

The implications of any visual impairment, regardless of cause, are devastating. Despite advances in AMD treatment, it remains one of the most common eye diseases leading to blind registration in the UK (Rahman et al, 2020). A seminal study by Stanford et al (2009), explained how participants' experiences of AMD aligned to Kubler Ross's theory of stages of grief, as they mourned the loss of their eyesight. The experience of living with AMD cannot be underestimated and highlights the importance of empathy and support in any setting and by all members of the healthcare team.

Many eye clinics and eye hospitals have access to an eye clinic liaison officer (ECLO). The ECLO is pivotal in signposting emotional, financial and practical support for patients (Llewellyn et al, 2019), particularly as patients' eyesight deteriorate and can limit their daily activities.

The real world of the patient with AMD is intensified by what is already known about the social and psychological issues in common with the older population, such as low mood and social isolation. AMD-related factors such as Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS) (visual hallucinations experienced by some people with a severe visual impairment), loss of independence due to not meeting the eyesight requirements to drive or use public transport safely, and falls risk, puts further limitations on a person's independence and subsequent wellbeing.

Conclusion

Scientific advances in AMD have improved patient outcomes. However, to ensure that patients receive the treatment they need in a timely manner, more could be done to promote awareness of the signs and symptoms of AMD and also provide access to regular eye tests. Community nurses can contact ophthalmic healthcare professionals for advice or to discuss concerns about patients undergoing IVT. Nonetheless, community nurses have a role to play in health education and health promotion about AMD. Understanding not only the physical manifestations of AMD but also the psychological and social impacts of AMD on a patient's wellbeing can influence patient-centred care, wherever that care takes place.

Key points

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) will increase in prevalence as the population ages

- Currently there is no treatment for dry AMD but people with wet AMD may benefit from intravitreal injections

- People with AMD may lose their central vision and this may impact on self-care, independence, and physical and psychological well-being.

CPD reflective questions

- What have you learned about the anatomy and pathophysiology underpinning age-related macular degeneration (AMD)?

- How can you inform your practice with knowledge about eye health and AMD?

- What is the community nurse’ role in supporting people who may have a visual impairment as a result of AMD?