Public health nurses (PHNs) in Ireland are registered general nurses who have also completed a post-graduate higher diploma in public health nursing at an accredited university. In contrast with community nursing services in the UK and elsewhere, the public health nursing service in Ireland operates as a generalist service providing both public health and wellbeing services (similar to health visitors in the UK) and clinical nursing services (similar to district nurses in the UK) to a wide range of client groups (Hanafin and Dwan O'Reilly, 2015). Providing nursing services in the community is challenging, not least because of the need for complex case management as well as effective and extensive networking and brokering abilities (Leary, 2019a). A number of challenges relating to staffing issues, caseload and workload, communication, discharge planning, lack of clerical support and increased documentation were identified by PHNs in Ireland in a survey carried out by the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation (2013). These issues are likely to give rise to considerable stress, which, in turn, can result in burnout.

Burnout has been described as a persistent dysfunctional state resulting from prolonged exposure to chronic stress (Chan et al, 2013). Commonly agreed explanations of burnout condition include three components, developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981):

- Emotional exhaustion

- Depersonalisation

- A decreased feeling of personal accomplishment.

Health professionals, including nurses and doctors, are at increased risk of burnout due to the stressful demands of their job (Yao et al, 2013), and varying levels of burnout have been reported among nurses. The RN4Cast international study reported that between 10% (the Netherlands) and 78% (Greece) of nurses regarded themselves to be burnt out (Aiken et al, 2013). In presenting the findings from Ireland, Scott et al (2013) noted that the majority of nurses working in medical and surgical units across the Irish acute hospital sector reported moderate to high levels of burnout. These findings were strongly related to low levels of job satisfaction as well as staffing challenges, resource inadequacy and poor nurse participation in hospital affairs.

Research on burnout among health professionals has identified a relationship between burnout and a number of demographic and organisational factors, including, for example, position held; annual income; shift type; and household economic wellbeing (Flinkman et al, 2010; Tziner et al, 2015; Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017; Tarcan et al, 2017). Winsett et al (2016) reported that workload complexity and interruptions during the course of work have an impact on the levels of burnout and can also result in medication errors.

In addition to the impact of burnout on patients, this issue has been widely studied in research related to the retention of staff. An integrative review of the literature by Flinkman et al (2010) reported that if nurses had experienced burnout, they were more likely to report intending to leave their employment. In an analysis of retention issues relating to new graduates in Ireland, Brady (2010) reported an association between a higher mean burnout score and increased frequency of thinking of leaving nursing. This finding has also been identified in other international studies (Tourangeau and Cranley, 2006; Flinkman et al, 2010; Tziner et al, 2015; Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017; Tarcan et al, 2017).

Some consideration has been given to burnout among nurses working in the primary care sector internationally. Monsalve-Reyes et al (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of burnout among primary care nurses and reported that low personal accomplishment is the most widely affected dimension of burnout, presenting in 31% of their sample. This was followed by emotional exhaustion, which was observed in 28% of the nurses in the sample. The lowest level of prevalence corresponded to depersonalisation, which affected 15% of the nurses included in the study.

The present paper described the findings of a study involving public health nurses in Ireland, a group that has not been considered before with regard to the issue of burnout.

Methodology

The purpose of this study is to examine the prevalence of burnout, as measured using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, among public health nurses and to compare relationships between burnout, demographic and work characteristics across this group of nurses.

This paper reports on a secondary analysis of quantitative data collected on behalf of the Public Service Pay Commission (PSPC) examining predictors of intention to leave using a two-stage cascading sample design. The methodology is reported in detail in the main report (Research Matters, 2019).

Questionnaire development

A questionnaire for use in the study was developed through:

- A scoping review of peer-reviewed and grey literature and instrumentation

- Contact with developers of previously validated scales or indexes

- Advice from researchers with expertise in the area (including PSPC's advisors on this study)

- Interviews already conducted with human resource personnel and nurse managers

- Pre-testing (n=4) and piloting (n=107) with nurses.

The questionnaire was divided into four sections: About your job, About your workplace, Job intentions and About you.

In total, the questionnaire for nurses included 46 questions and, within this, the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Cammann et al, 1979), containing four items, was included to measure burnout. The Cronbach's alpha for the inventory was .864.

Data collection

Every director of nursing on the Health Service Executive National Office of the Nursing and Midwifery Services Director (ONMSD) database of directors was contacted by the ONMSD to:

- Inform them about the study

- Request their assistance in circulating a separate invitation email to all the nurses working in their organisation (including part-time and student intern employees)

- Send a text message to nurses that included a link to the survey, which could be completed on a smart phone, as well as on a computer or laptop if an email address was not available

- Publicise the link to the survey within the organisation including, if available, placing the link on the intranet to which only staff had access.

In addition, three reminder emails were sent by the ONMSD to all directors of nursing over the 3-week data-collection period.

Response rate

In total, 3769 nurses took part in this study and, of these, 136 indicated they were public health nurses (PHNs). This yielded a minimum overall response rate of 9.7% and an estimated rate of 12.3%, taking into account an adjustment for those who were on leave. The actual response rate may be higher, since the two-stage sampling means that it is possible that not all nurses in the population of 42 041 nurses received an invitation to participate. Finally, the 136 PHNs were included in the sample.

Data analysis

The data were exported from the internet survey provider Survey Monkey into IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v. 25.0), and descriptive and inferential statistics were generated (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of the characteristics of public health nurses included in the study

| Age group | % | Type of contract | % | Country in which basic nursing/midwifery qualification was obtained | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 years or younger | 29.3 | Permanent full time | 80.1 | Ireland | 83.7 |

| 31–40 years | 4.9 | Permanent part time | 14.7 | Other EU country | 15.4 |

| 41–50 years | 38.2 | Fixed term full-time | 5.1 | Non-EU country | .8 |

| 51 years or older | 27.6 |

Ethical issues

Ethics approval for this study was sought from, and granted by, the research ethics committee of the School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin. Ethical issues were considered and addressed throughout the process, particularly in areas of confidentiality, anonymity and data protection. Confidentiality implies that research data that include identifiable information on participants were not to be disclosed to others without the explicit consent of the participants. Only the minimum amount of personal data required was sought, and personal data were not used for any purpose other than that specified at the time of the collection. All data were anonymised, and all research outputs were checked carefully to ensure that no individual would be identifiable. In addition, all appropriate steps were taken to ensure that data were held in a secure way. This included the removal of direct identifiers, the use of pseudonyms and the use of technical means to break the link between data and identity. Both system and physical security safeguards were put in place to ensure that the data were protected. In order to ensure informed consent, a detailed information sheet was provided to participants, which included contact details of the research team, in case they had any questions.

Limitations

All research has some limitations. The overall response rates in this study were lower than desired, at 12.3% of all nurses working in Ireland and, while the data were weighted to provide nationally representative estimates, there is no way of empirically assessing the extent to which particularly enthusiastic or particularly disenfranchised individuals may have responded. This potential bias should be borne in mind when interpreting the results.

Findings

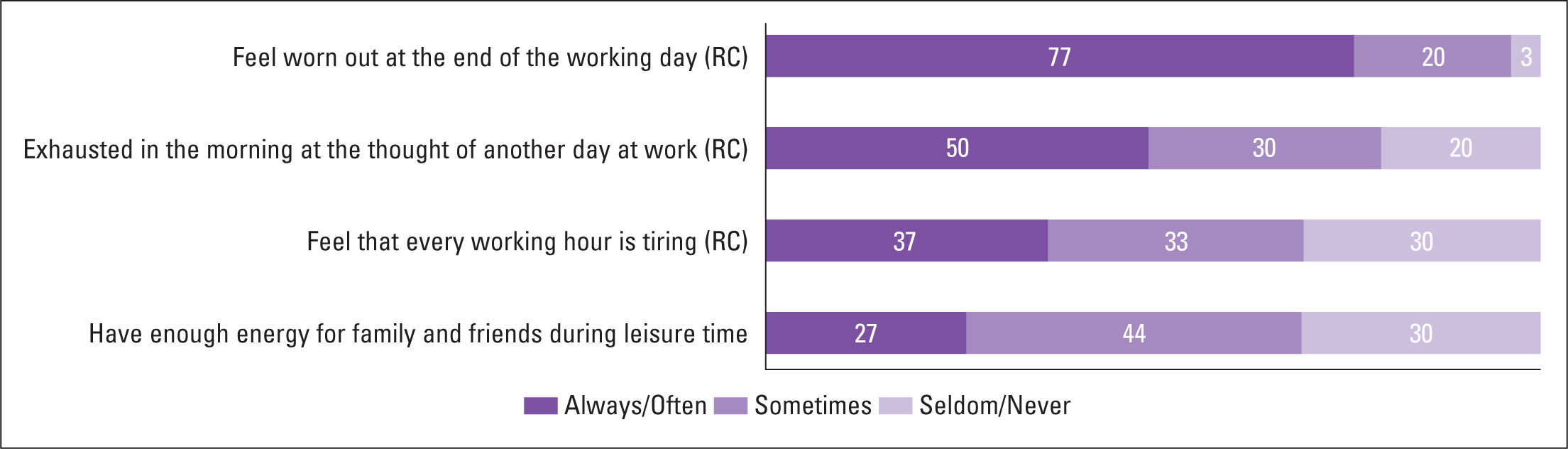

The main findings from the study showed that PHNs report moderate levels of burnout. More than one-quarter of PHNs (28%) who took part in the study reported always feeling worn out at the end of the day, and a further 38% reported feeling this way often. Less than 1% reported never feeling this way. One in every 10 respondents reported feeling that ‘everyday working is tiring’ always, and a further 14% reported feeling this way often. Only 10% reported having enough energy for family and friends during leisure time.

An overview of the findings from individual elements of the scale is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Findings relating to individual scale elements

Figure 1. Findings relating to individual scale elements

Mean differences by demographic characteristics

Responses to individual items on the scale were combined to form a scale score expressed as a percentage, and items with ‘(RC)’ in Figure 1 have been reverse coded to produce the index, meaning that low values are recoded to high and vice versa. The use of scale means allows for comparisons within the PHN group by demographic characteristic and with other groups who took part in the study.

The overall scale mean for PHNs was 53.2% and, while there were no statistical differences according to the type of contract, number of hours worked, highest educational qualification, number of years in the current job or place of birth, some differences were noted, as follows:

- Younger PHNs were more likely to report feeling burnt out (68%) compared with those aged 51 years or over (47%), who reported the lowest levels

- PHNs whose highest level of qualification was a primary degree were least likely to report feeling burnout (31%) compared with those who held a masters or doctoral degree (54.5%)

- PHNs who reported working on a fixed-term full-time contract were more likely to report feeling burnout (70%) compared with those who were on a permanent part-time contract (49%).

Comparisons with other nursing grades in acute and managerial positions

The findings presented in this section compare the findings between PHNs and other nursing grades who took part in the study. The overall findings from the main analysis showed that nurses overall had a mean score of 61% on the burnout index, indicating moderate to high levels of burnout. Staff nurses had significantly higher levels of burnout (64%) than all other grades except student interns (67%). Burnout scores were lowest among directors/assistant directors (45%) and ‘other’ grades (e.g. corporate, education) (44%). Significantly higher levels of burnout were reported by respondents working in the acute sector (65%) compared with those working in the community (56%) and other settings (37%).

Correlations between burnout and workplace issues among PHNs

A correlation analysis of the relationship between burnout and a number of workplace issues, using data only from PHNs, was considered, and the strength of the relationship identified. A positive correlation indicates the extent to which those variables increase or decrease in parallel; a negative correlation indicates the extent to which one variable increases as the other decreases. For example, item 1 in Table 2, ‘satisfaction with the physical demands placed on you during work’, is negatively correlated with burnout, meaning that the lower the level of satisfaction, the higher is the level of burnout reported.

Table 2. Areas taken into account relating to the workplace most strongly correlated with burnout

| Statement | Correlation |

|---|---|

| (Dissatisfaction with) The physical demands placed on you during work | –655** |

| (Agreement that) I have constant time pressure due to a heavy work load | .534** |

| (Agreement that) Too much is expected of me in my job | .521** |

| (Agreement that) The work environment is too demanding | .493** |

| (Dissatisfaction with) The physical working conditions | –.490** |

means that items are statistically significant at the 0.001 level

The findings showed that burnout among PHNs is strongly correlated with the physical demands placed on individuals during work, having constant time pressures, excessive high expectations of individuals, the work environment being demanding and dissatisfaction with the physical conditions. The five areas taken into account in this study that were identified as having the strongest statistically significant correlations are presented in Table 2.

Correlations between burnout and attitudes to work

The correlations presented in Table 2 draw only on data collated from PHNs. An analysis of the relationship between burnout and attitudes to work were considered, and the strength of the relationship identified. The findings showed that feelings of burnout are strongly related to job dissatisfaction, not feeling like going to work, low energy levels at work and thinking about leaving the organisation. These are highlighted in the following five areas taken into account in this study that were identified as having the strongest statistically significant correlations (Table 3).

Table 3. Areas taken into account relating to the workplace most strongly correlated with burnout

| Statement | Correlation |

|---|---|

| All things considered, I am satisfied with my job * | –598** |

| All in all, I am satisfied with my job | –.593** |

| When I get up in the morning I feel like going to work | –564** |

| At work I feel full of energy | 522** |

| I think about leaving the organisation | .521 |

means that items are statistically significant at the 0.001 level

Discussion

The findings from the present analysis showed that PHNs working in the Health Service Executive in Ireland experience moderate levels of burnout. More than one in four of the 136 PHNs who took part in this study reported always ‘feeling worn out at the end of the working day’ (28%), and about 30% reported either always or often feeling ‘exhausted in the morning at the thought of another day at work’. Some 10% reported that they always have enough energy for family and friends during leisure time.

At 53.2%, the scale mean for PHNs is not statistically different according to a number of demographic characteristics, although younger PHNs, those who hold a masters or doctorate qualification and those working on a fixed-term full-time contract were all more likely to report feelings of burnout compared with their colleagues. Lower levels of burnout were reported among PHNs compared with staff nurses working in acute settings, and this finding is in line with those reported in a meta-analysis of burnout among primary care nurses by Monsalve-Reyes et al (2018), which identified similar type comparisons. An association between intention to leave and burnout has been reported in several studies, including in Ireland and, where nurses reported experiencing burnout, they were also likely to report intending to leave their employment (Brady, 2010; Flinkman et al, 2010).

A number of issues relating to the work environment were strongly correlated with burnout and, of those taken into account in this analysis, the physical demands placed on PHNs during work were identified as being most strongly associated. Other areas included constant time pressure due to a heavy workload, high expectations of individuals, the work environment being too demanding and dissatisfaction with the physical conditions. These findings are not surprising in the context of the impact of the austerity measures put in place to deal with the sovereign debt crisis in 2008, including the implementation of the Financial Emergency Measures in the Public Interest Acts (FEMPI). A report commissioned by the Department of Health noted that the reduced spending on health services over the period of austerity was achieved, in part, through reductions in workforce pay, restrictions on recruitment, ceilings on staffing, redundancy schemes and incentivised early retirement (World Health Organization, 2014). These interventions resulted in a substantial reduction in the number of nurses working in the Health Service Executive, including in the number of whole-time-equivalent PHNs, which was reported to be a mere 1525 in March 2019 (Health Service Executive, 2019).

In parallel with reductions in nursing personnel over the 10-year period spanning 2008 to 2018, there was an increase in the number of patient discharges from hospital (from 592 133 in 2009 to 633 155 in 2018) as well as a 10% decrease in the number of acute hospital beds, both of which have an impact on the need for nursing care in community (Department of Health, 2019). While the work of PHNs is broader than that of district nurses in the UK, there is nevertheless considerable overlap in the challenges they experience (Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation, 2013; Leary, 2019a). These challenges can create high stress levels leading to burnout that are likely to impact negatively not just on the individual themselves but also on the service they provide.

Conclusion

The findings of the analysis in this study indicate that, as a group, PHNs in Ireland are experiencing moderate levels of burnout, and it is likely this finding is relevant to nurses in other jurisdictions providing similar types of services. Consideration needs to be given to reducing pressures arising from heavy workloads and unrealistic expectations of what can be delivered with the available resources. This is particularly relevant for public health nursing, a service where it can be hard to articulate how outcomes are impacted by the service and where it can be difficult to evaluate cost-effectiveness (Leary, 2019b).

KEY POINTS

- Burnout—characterised by emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation—is common among health professionals

- The study examined burnout in public health nurses in Ireland, through a secondary analysis of quantitative data collected on behalf of the Irish Public Service Pay Commission looking at predictors of intention to stay or leave the health organisation

- The findings showed moderate levels of burnout among the 136 PHNs surveyed, with more than a quarter (28%) reporting always feeling worn out at the end of the day and only 10% reporting having enough energy for family and friends during leisure time

- Younger PHNs (68%), those who held a masters or doctoral degree (54.5%) and those working on a fixed-term full-time contract (70%) were more likely to report feeling burnout

- More needs to be done to support nurses working in community to reduce the levels of burnout among these health professionals.

CPD REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Do you recognise the characteristics of burnout in your workplace?

- Are there specific support measures in your workplace to minimise burnout among personnel?

- Are there steps you can take to minimise burnout among colleagues?

- Can you identify the reasons for burnout?