An estimated 90 000 people in community settings have long-term indwelling urinary catheters (Gage et al, 2017). Urinary catheters are invasive medical devices, and there are risks and benefits associated with their use. This article examines the clinical indications for indwelling urinary catheterisation and the diagnosis and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI). There is little data on the number of people with long-term urinary catheters being cared for in the community. A UK study extrapolated data from the south and west of England of people who had indwelling catheters for 90 days. They estimated that over 90 000 people in the UK had long-term catheters. They found most people were initially catheterised in hospital and that prevalence increased with age. Catheterisation was more common in people with neurological disease, and suprapubic catheterisation was more common in women (Gage et al, 2017). An Irish study found that 31% of patients aged 85 years and over who were receiving community nursing care had an indwelling catheter (Forde and Barry, 2018). In some instances, initial catheterisation is inappropriate; in other cases, it was appropriate at one point during the person's hospital stay but is no longer clinically appropriate (Nazarko, 2017).

Costs and benefits of urinary catheterisation

Urinary catheters used appropriately can enable people with urinary incontinence to remain dry when other methods have failed. They can enable people who are dying to remain at home. They can help enable severe pressure ulcers to heal. Table 1 indicates the appropriate indications for indwelling urinary catheterisation (Adams et al, 2012).

| H | Haematuria |

| O | Obstruction |

| U | Urologic surgery |

| D | Decubitus ulcers: open sacral or perineal pressure ulcer in an incontinent person |

| I | Input/output monitoring |

| N | Not for resuscitation/end of life care: comfort |

| I | Immobility due to physical restraints |

Urinary catheters can also cause harm and ill-health. Around 50% of people who have long-term catheters experience problems including pain, tissue damage, decreased mobility and hospital attendances associated with blockage (Khan et al, 2007). These non-infective complications are five times more common than infective complications (Saint et al, 2018). Urinary catheters increase the risk of infection and life-threatening bacteraemia (National Audit Office, 2009).

Indwelling urinary catheters and infection risks

Adults with indwelling urinary catheters are at increased risk of developing a CAUTI. Each year, an estimated 4% of people with long-term urinary catheters will develop a CAUTI (World Health Organization (WHO), 2018). The urinary catheter provides a portal of entry into the bladder. Bacteria can enter the bladder during catheter insertion, through the catheter lumen and along the catheter urethral interface. Infection risks rise the longer a catheter remains in place, because the bladder becomes colonised with bacteria, and these bacteria can cause infection (Salgado et al, 2003). The presence of a urinary catheter enables bacteria to form a biofilm. This is a sticky, slimy layer that protects bacteria from both antimicrobials and the person's natural immune response (Nicolle, 2005). When a bladder fills and empties normally, bacteria are flushed away; this protection is lost when a person has a urinary catheter on continuous drainage.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Although urine is normally sterile, certain groups of people including those who are catheterised may have bacteria present in the urine. When these bacteria do not cause a symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI), this (often incidental) finding is known as asymptomatic bacteriuria. When this is associated with a urinary catheter, it is referred to as catheter-acquired asymptomatic bacteriuria (Hooton et al, 2010).

When a person has an indwelling urinary catheter, the bladder becomes colonised with bacteria. The urine becomes cloudy and smelly, and it tests positive for leucocytes and nitrates. If urine is cultured, a mixed growth of bacteria is often found. In the absence of clinical symptoms of UTI, treatment is not required (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2012; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018).

Table 2 (SIGN, 2012; NICE, 2018) outlines key messages on asymptomatic bacteriuria.

| Bacteriuria is not a disease |

|

| Tests to identify bacteria or white cells in the urine are not diagnostic of urinary tract infection |

|

| Only urine obtained by needle aspiration of the bladder eliminates the risk of contamination and false positives |

|

| Routine culture is not required to manage lower urinary tract infection in women |

|

Diagnosing UTI in people with catheters

A UTI is an infection in any part of the urinary system, including the kidneys, bladder, ureters and urethra. The term catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is used to refer to individuals with symptomatic infection (Hooton et al, 2010). In the UK, UTIs are the second most common reason for prescribing antibiotics (UK Government, 2011).

UTIs in older people are over-diagnosed and over-treated. An estimated 40% of cases of UTI in older people are incorrectly diagnosed (Woodford and George, 2010). Urine dipsticks are often used to check for bacteriuria by checking nitrate and leukocytes in urine. Both urine dipsticks and microbiology are unable to distinguish ASB and CAUTI. The prevalence of ASB is increased in older people and is so common that urine tests and culture are not reliable diagnostic tests (Ferroni and Taylor, 2015; NICE, 2015).

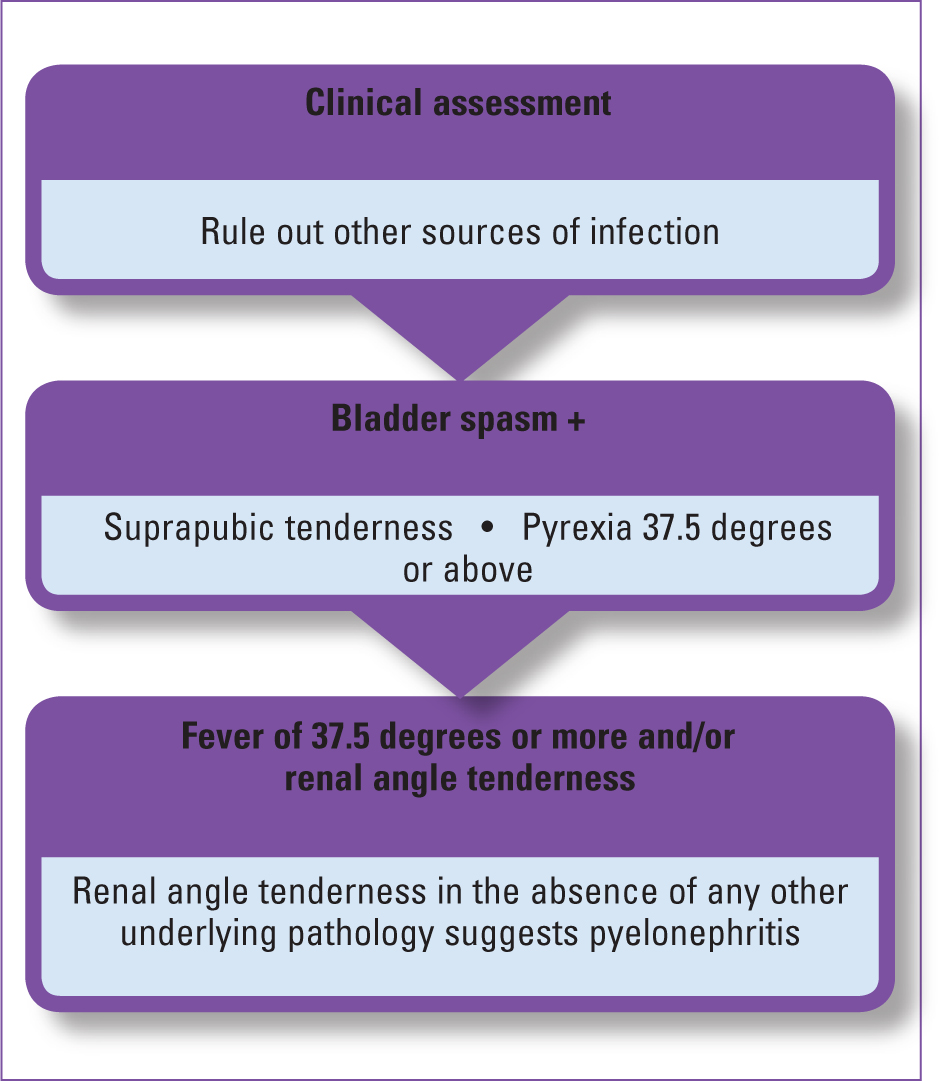

Diagnosis of symptomatic infection can be difficult, and a clinical assessment is required. Figure 1 (author's own work) illustrates diagnosis of CAUTI (SIGN, 2012; Rowe and Juthani-Metha, 2014; NICE, 2018; WHO, 2018).

Treating CAUTI

Current CAUTI guidelines do not provide specific advice and treatment on CAUTI in older people or people with long-term catheters (SIGN, 2012; NICE, 2018). Table 3 summarises treatment guidelines.

| Guidance | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Consider removing or, if not possible, changing the catheter if it has been in place for more than 7 days |

|

| Do not delay antibiotic treatment |

|

| Send a urine sample for culture and susceptibility testing |

|

Patients should be advised of the possible adverse effects of antibiotics, including diarrhoea and nausea. The patient should be advised to seek medical help if symptoms worsen at any time or do not start to improve within 48 hours, or the person becomes systemically very unwell.

Reassessment

The patient should be reassessed when results of urine culture are available, and choice of antibiotics should be reviewed. If a broad spectrum antibiotic was initially prescribed and the patient is sensitive to a narrow spectrum antibiotic, then the antibiotic should be changed.

The patient should be reassessed if symptoms worsen or do not start to improve within 48 hours.

Referral and specialist advice

If the patient has clinical features that suggest sepsis or another serious illness, they should be urgently referred to hospital (NICE, 2018).

NICE (2018) recommends that clinicians should consider referral or seeking specialist advice if the patient is:

Preventing CAUTI

The best way to prevent CAUTI is to avoid urinary catheterisation unless it is clinically indicated. Inappropriate indications include using indwelling catheters as a substitute for nursing care for a person with incontinence, using them for prolonged periods postoperatively without an appropriate indication and to obtain a urine sample when the person is able to void normally.

Urinary catheterisation should be performed using sterile equipment, and aseptic technique should always be maintained during insertion and aftercare procedures. Hands must be properly washed before and after procedures and during day-to-day care. A closed drainage system should be maintained.

Bladder irrigation or washout and instillation of antiseptics or antimicrobial agents do not prevent CAUTI and should not be used (WHO, 2018).

The hazards of treating ASB

Healthcare can harm as well as heal, and, when providing care, it is important to work out the risks and benefits of treatment. There are no clinical benefits in treating ASB (Zalmanovici Trestioreanu et al, 2015; Nicolle, 2016).

Inappropriately diagnosing and treating ASB as an infection exposes the individual to a number of hazards. Antibiotic use affects the microbiome and can decrease natural immunity and increase the risk of infections such as Closterioides difficile (Amon and Sanderson, 2017). Antibiotic use can also lead to antibiotic resistance, and this can affect not only the individual but also the general population (Zalmanovici Trestioreanu et al, 2015).

The individual may suffer adverse effects, such as oral or genital Candida infection, antibiotic-related nausea and diarrhoea. The person may develop an allergy to the antibiotic and develop symptoms of allergy including a rash.

The community nurse's role in reducing CAUTI

Most people who are catheterised acquire their first catheter in hospital (Gage et al, 2017). Evidence indicates that, in around 30–50% of cases, the indication for catheterisation is unclear (Nazarko, 2017). In other cases, such as urinary retention associated with prostatic hypertrophy, there may be a clear clinical indication and plans to carry out a TWOC in the future. NHS Improvement has provided a range of tools including the catheter passport to support management and removal of urinary catheters (NHS Improvement, 2018). Many areas have adopted catheter passports, and they can help community nurses to manage catheters. Carrying out TWOC in community settings can reduce the time catheters are in situ, and reduce the risks of infection and other adverse effects. TWOC will be discussed in a future article.

Community nurses are normally responsible for catheterisation in the community, and maintaining strict asepsis can reduce infection risks.

Community nurses have an important role to play in the diagnosis and treatment of CAUTI, and the well-educated nurse who can differentiate between ASB and CAUTI can reduce the risk of harm to the individual with a catheter and help reduce the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

The person with a urinary catheter and their caregivers may consider that, if urine is cloudy and smelly, this is an indicator of infection, and the community nurse or the GP may be pressured to prescribe antibiotics. The catheter passport provides some information about when an infection may be present; however, patients and caregivers may still consider cloudy, malodorous urine to indicate infection. Some community trusts provide patient information leaflets. The British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) has a helpful leaflet that can be used if there is no local guidance (BAUS, 2017).

Conclusion

As the UK population continues to grow older, and increasing numbers of people with catheters are cared for in the community, the community nurse's role in the management of urinary catheters and the diagnosis and treatment of complications including CAUTI is growing. Community nurses who have a good understanding of ASB and CAUTI can ensure that CAUTI is promptly diagnosed and treated and that people with ASB are not inadvertently exposed to the hazards of antibiotic therapy.