The number of people in England with two or more chronic conditions is expected to double to nearly 10 million over the next 20 years, increasing the demands on health and social care services (Kingston et al, 2018). The vast majority of this care for older people with multiple morbidities takes place in primary care and community settings. As well as having two or more chronic conditions, many older people have other impairments, such as declining cognitive ability or sensory losses, making it more challenging for them to navigate complex and fragmented care provided by multiple organisations. The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019b), published in January 2019, and the associated NHS Long Term Plan Implementation Framework (NHS, 2019a), published in June 2019, set out clear expectations that local NHS organisations will increasingly focus on population health and local partnerships with local authority-funded services through new integrated care systems (ICSs). The Implementation Framework states that the emerging ICSs will be clinically led, and David (2019) makes the case for nurses to play substantial roles in providing advice and leadership within these emerging systems. This article explores two models of integrated care from the Netherlands and asks whether there are lessons to be learnt from these models, as well as what the leadership implications might be.

Background

The Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that the UK spent 9.8% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare in 2018 (OECD, 2019b). This equates to US$ 4070 per capita, only slightly higher than the OECD average of US$ 3992 per capita. A near equivalent is the Netherlands spending 9.9% of its GDP on healthcare, equating to US$ 5288 per capita. Given the economic climate in the UK, it is unlikely that the overall economic position, with respect to healthcare expenditure, both in terms of GDP and per capita spend, is likely to improve, although the way in which it is spent is likely to change. On the other hand, demand for healthcare is expected to rise. The Netherlands has a considerably different healthcare structure to that in each of the four countries in the UK. For example, it is based on a statutory not-for-profit health insurance system, which covers both health and social care. Individuals cannot be charged more for their premiums because of factors such as health status or age, but there are contributions to costs, such as the ‘annual deductible’ of around £290 per year before insurance cover starts to pay. There is a universal social insurance scheme (AWBZ) covering home care and care in residential facilities, including accommodation costs. It also has close links with the health insurance system, as long-term hospital stays, rehabilitative services and nursing care are also covered in the programme (Robertson et al, 2014). Life expectancy in the Netherlands is 83.7 years for men and 86.2 years for women, compared to 83.8 years for men and 86.1 years for women in the UK, according to OECD data (2019c). The proportion of the population aged 65 years and over was 17.26% in the UK and 17.09% in the Netherlands in 2014 (OECD, 2019a).

Integrated care systems

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2013) describes integrated care as:

‘The management and delivery of health services such that people receive a continuum of health promotion, health protection and disease prevention services as well as diagnosis, treatment, long-term care, rehabilitations and palliative care services through the different levels and sites of care within the health system according to their needs’.

Struckmann et al (2018) identified relevant models and elements of integrated care for multi-morbidity and subsequently identified which of these models and elements are applied in integrated care programmes for multi-morbidity in the EU and US. Their findings were that most elements of integrated care in multi-morbidity refer to the WHO system components set out below:

The five elements of integrated care models most frequently identified by Struckmann et al (2018) were:

The enabling factors for these elements were:

Models of integrated care from the Netherlands

Two models of integrated care are gaining prominence, both from the Netherlands. These are the Buurtzorg model and Embrace.

The Buurtzorg model (‘Buurtzorg’ translates literally as ‘neighbourhood care’) is described by Maybin (2019) in her blog at the King's Fund as a social enterprise in the Netherlands. It started in 2006 and is based on small teams of nursing staff delivering personal, social and clinical care to people in their own homes in a given neighbourhood. Only one or two staff work with each individual and their informal carers. The focus is to support independence by using appropriate resources available in the individual's social networks and neighbourhood. The nursing teams make all the clinical and operational decisions themselves within in non-hierarchical self-managed teams. Support is available from a coach to facilitate constructive teamwork.

The Embrace model is similar in many respects to Buurtzorg. Uittenbroek et al (2018) published a comprehensive cost-effectiveness study in the Netherlands and found that, within a time horizon of 12 months, it was not cost-effective. The study was conducted using Dutch costs, and it should be remembered that the Dutch health and social care system is quite different to the UK system and spending per capita in the Netherlands on healthcare is higher than in the UK. Both the Buurtzorg and Embrace models are integrated within the neighbourhood but not necessarily as comprehensively at place and system level as proposed in English ICSs.

The point that emerges from the Buurtzorg model is the higher level of user satisfaction from service users of both models and high levels of staff engagement and fulfilment derived from more inclusive leadership styles and less hierarchical structures (Drennan et al, 2018). As shown in Table 1, the Netherlands has more bed capacity in residential long-term care facilities than the UK (OECD, 2019d). This is important because the Netherlands cost-effectiveness study of the Embrace model may have included calculations based on greater availability of lower cost long-term residential beds. Typical English costs are more likely to be calculated against higher-cost acute-care beds, and this is a potential area for further research.

| Number of beds in long-term residential care facilities | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Variable | Country | |||||||||

| Number | Netherlands | 172 220 | 172 270 | 240 121 | 239 206 | 239 887 | 235 253 | 234 372 | 236 345 | - |

| UK | 524 609 | 551 363 | 550 005 | 548 973 | 549 089 | 548 397 | 545 010 | 542 627 | 529 467 | |

| Per 1000 population aged over 65 years | Netherlands | 67.8 | 66.4 | 88.4 | 84.7 | 82.2 | 78.2 | 76 | 74.8 | - |

| UK | 51.6 | 53.2 | 51.6 | 50 | 48.7 | 47.6 | 46.5 | 45.6 | 43.8 | |

For the English NHS, Stokes (2016) concluded that: ‘Integrated care, in its current manifestation, is not a silver bullet that will enable health systems to simultaneously accomplish better health outcomes for those with long-term conditions and multi-morbidity while increasing their satisfaction with services and reducing costs. The current financial climate might mean that other means of achieving prioritised aims are required in the short-term, with comprehensive primary care and population health strategies employed to better prevent/compress the negative effects of lifestyle-associated conditions in the longer term’.

NHS England (2019a) set out their vision for the design of ICSs in England in June 2019. These are based on:

The emphasis on comprehensive primary care and population health strategies is welcome, and that, together with the improved vision for ICSs and supporting infrastructure, including IT development, may go some way to ameliorating Stokes (2016)'s concerns about integrated care not being a silver bullet. Much will depend on the funding arrangements for ICSs and what changes emerge in the long-awaited reforms to social care in the form of the delayed green paper (Duncan and Trigg, 2019).

Thriving ICSs will be expected to have strong collaborative and inclusive leadership, including local government and the voluntary sector. They will also be required to adopt a proactive approach to identification and development of future system leaders at all levels. So, what does this mean for nurse leadership?

Leadership styles

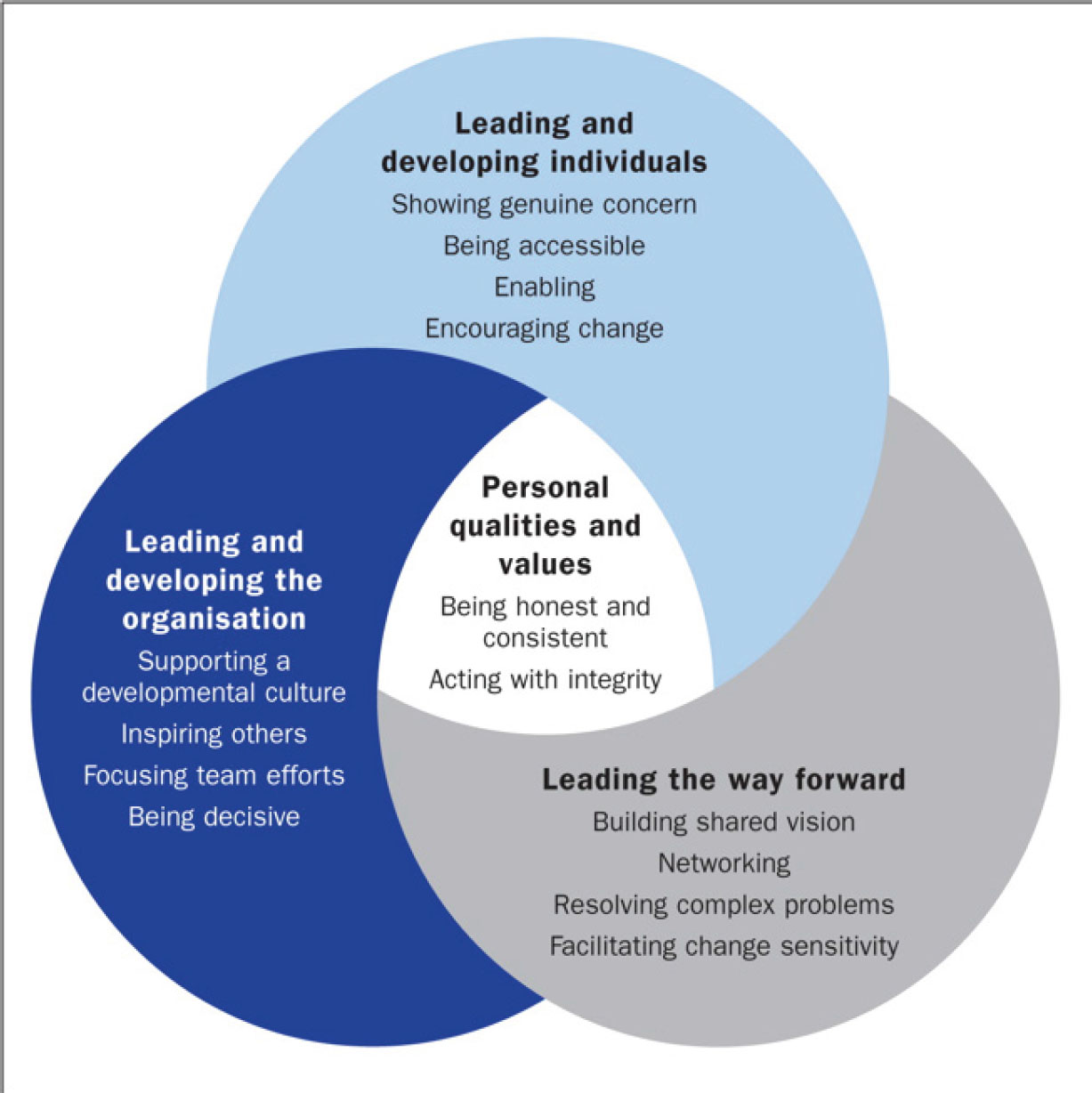

Alban-Metcalfe (2017) made a distinction between the ‘what’ (competency) and the ‘how’ (behaviours) of leadership. Alban-Metcalfe (2017)'s view is that competency-based leadership training is not enough for effective leadership and organisational success. How the competency is applied is equally important. Real leadership is about engagement, ensuring behaviour has a positive impact on colleagues, service users and their families. This involves team working, collaboration and creating a culture where ideas are sought, listened to and valued. In short, it means creating a learning environment where mistakes are acknowledged and opportunities are sought to learn from them. This approach, known as the engaging leadership model, is discussed in further detail by Harris and Mayo (2018) and is illustrated in Figure 1.

Engaging transformational leadership is also used by the NHS Leadership Academy (2013) where further resources are available.

In determining how well-led a trust is, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) (2017) takes into account leadership capability and capacity, culture, vision and strategy, governance, staff and patient/public engagement, and the drive for continuous improvement. CQC reports (2017) refer to some trusts changing the leadership team to help drive improvement. For others, it was about empowering existing staff to take leading roles in effecting organisational change. The CQC (2017) also reports that those trusts who recognised and used the potential of their staff saw improved patient outcomes and higher staff morale.

For nurse leaders, this means valuing and applying their professional expertise in community settings and applying engaging transformational leadership skills to create a genuine learning environment for themselves and their colleagues as they all move towards collective leadership. It also means having confidence in colleagues and developing, maintaining and nurturing flatter multidisciplinary teams. It will require multi-professional, team-based training, and all staff putting into practice a Dutch word that is the cornerstone of both the Buurtzorg and Embrace models: samenwerken. This can be translated as ‘working together’ or ‘co-operating’.

Conclusion

ICSs will be both an opportunity and a challenge for all professional staff. Knowledge and expertise are always important, but equally important is the way in which these skills are used to improve collaborative interdiciplinary working, professional development and collective leadership. All too often, continuing professional development and, indeed, initial professional training, has been focused on silo professionals, and this may be an opportunity to redress that focus to team-based professional development in more inter-disciplinary training, so that by working together, patient care and outcomes are improved. However, funding, workforce planning and appropriate skill mix will be crucial, as leadership skills on their own, however excellent they may be, will not be enough if resources are not available.