Approximately 50 000 people in the UK regularly perform intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC), an invasive procedure whereby the patient passes a non-retaining catheter into their bladder to assist in the drainage of urine when normal voiding is not possible (Wilks et al, 2020). This is due to chronic or acute urinary retention, in which the bladder is no longer able to empty, causing stagnation of urine (Balhi and Mrabet, 2020). Urinary retention may result from paralysis of the bladder muscle, making urination slow and painful, or from poor opening of the sphincter during urination (Balhi and Mrabet, 2020). It is usually performed as a clean (rather than aseptic/sterile) technique by patients or their family or personal carer; for this method, the use of a disposable or dry, reusable catheter is recommended, preceded by cleaning of the hands and perineum with a non-antiseptic solution (Balhi and Mrabet, 2020).

In the UK, disposable, single-use catheters are used almost exclusively; this contrasts with other developed countries, where catheters are commonly cleaned and reused multiple times, although cleaning methods have not been standardised (Wilks et al, 2020). There are three main types of catheters used for ISC, with the majority being single-use:

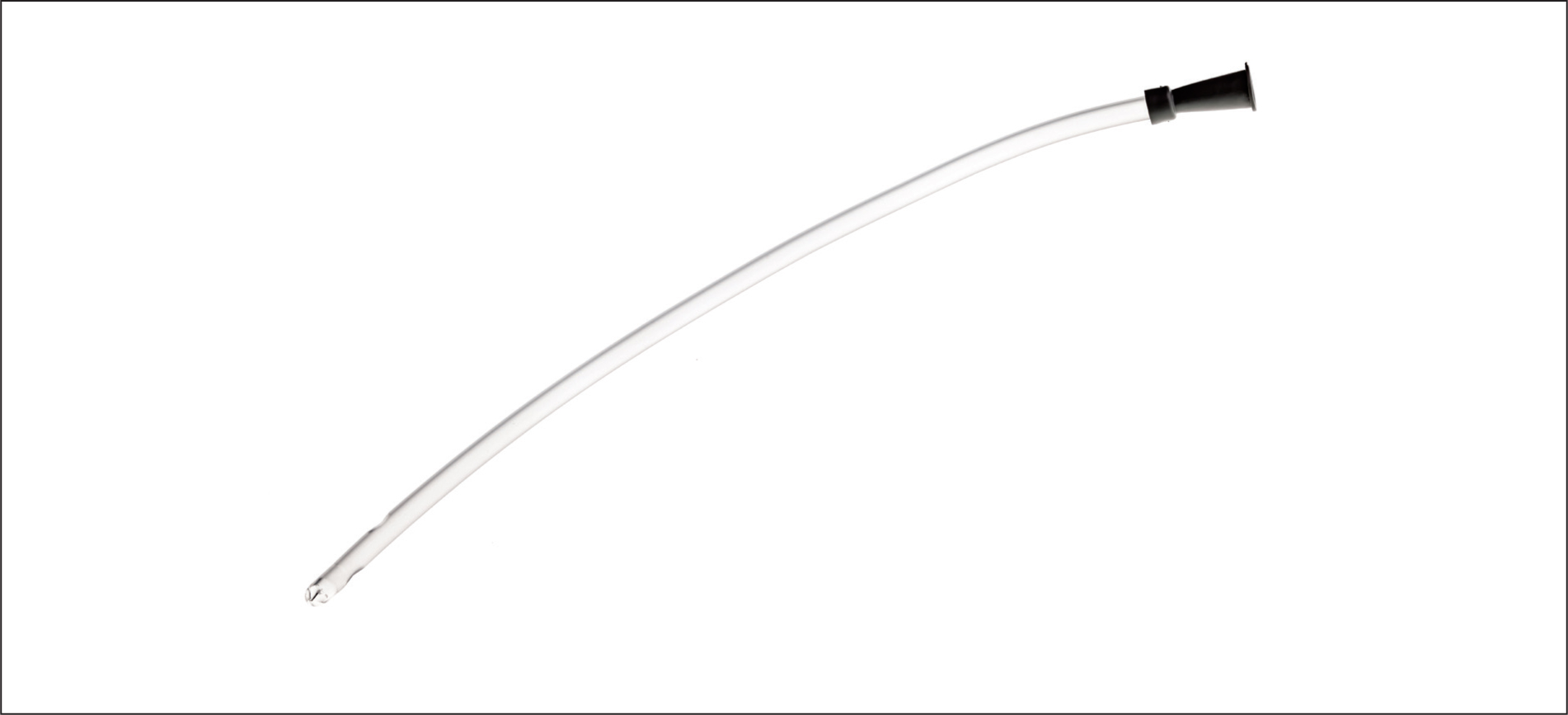

- Coated catheters have a hydrophilic coating that creates lubrication around the catheter when run under water before use, allowing for easier insertion into the urethra. These are single-use, disposable catheters and are usually made of either polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or silicone

- Non-coated catheters are the traditional intermittent catheter, and most are designed to be washed and reused. They are available in a variety of sizes and materials, including silicone, PVC, silver or stainless steel. Silver or stainless-steel rigid catheters are only suitable for women, due to the length of the urethra. These are less commonly used, due to needing to be cleaned and lubricated prior to use

- Pre-lubricated catheters can be used straight from the packet without any additional preparation. They are packed in a water-soluble gel for easier insertion and are often used by patients outside of the home setting, where adequate facilities for bladder emptying may not be available (Bladder and Bowel Community, 2022).

The challenges faced

ISC is recognised as the gold standard for the treatment of neurological bladders, promoting improved independence, quality of life and wellbeing (Holroyd, 2018) and reducing the risk of infection and damage to the bladder in comparison to indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheterisation (Balhi and Mrabet, 2020). However, there are barriers to, and complications associated with, the practice of ISC. These are frequently associated with patient-related factors and adherence and can be overcome with adequate training and assistance, in which community nurses can play a vital role. Possessing the appropriate knowledge to be cognisant of the common challenges encountered during ISC, and the skills and confidence to empower and assist patients to surmount these, is an essential part of the community nurse's toolkit. The challenges associated with ISC can be divided into three general categories: internal barriers, external barriers and environmental factors (Balhi and Arfaoui, 2021).

Internal barriers

These include physical and psychological factors. All of the physical barriers that can affect the quality of the ISC should be considered, such as poor eyesight, reduced manual dexterity, reduced mobility, the presence of pain, age and positioning (Balhi and Arfaoui, 2021). A study conducted by Bolinger and Engberg (2013) reported that 25% of women find positioning of catheters to be a challenge to ISC; the same study also revealed dexterity to be a common barrier, affecting 21% of people with multiple sclerosis. Additionally, Girotti et al (2011) showed that the adherence rate for patients older than 60 years was only 33%, compared with 86% for patients younger than 40 years. The same findings were reported by Cobussen-Boekhorst et al (2016), who showed that adherence can be negatively influenced by increasing age. The psychological barriers are no less formidable, with some participants of McClurg et al's (2018) qualitative study perceiving ISC to be a heavy practical and psychological burden, despite accruing 4–15 years of experience, and reportedly engaging in avoidance strategies, such as decreasing water intake. As ISC may need to occur up to 6 times a day, patients report finding catheterisation preparation more difficult than the catheterisation itself, alongside feeling constrained by the need to plan convenient times to catheterise themselves (Cobussen-Boekhorst et al, 2016). ISC can impact psychosocial functioning, with examples including impediments to patients' ability to enjoy social activities, travel abroad and stay away from home, due to the potential embarrassment of disclosing ISC use and its associated pragmatisms (McClurg et al, 2018).

External barriers

These include factors related to training and the type of catheter chosen. Most patients do not possess any knowledge of the anatomy of the urinary tract and their pathologies (van Achterberg et al, 2008; Ramm and Kane, 2011), with many never having seen a urinary catheter before (Ramm and Kane, 2011). Yet, prescribers and teachers of ISC often have overly high expectations of patients, especially in regard to being flexible about frequency of catheterisation (Cobussen-Boekhorst et al, 2016). Patients often do not have the opportunity to try different types of catheters during the learning period, despite the fact that the most comfortable type of catheter is dependent on many factors individual to the patient (Balhi and Arfaoui, 2021).

Environmental factors

These are mostly related to uncontrolled factors outside of the home setting, such as lack of privacy and suitable bathroom facilities. Lack of access to a bathroom affected 34% of Bolinger and Engberg's (2013) 44 community-dwelling participants, and all 11 of Cobussen-Boekhorst et al's (2016) participants reported feeling embarrassed and uncomfortable when performing ISC outside of their usual environment, with small bathrooms, insufficient lighting and sinks located outside of the toilet being some of the most commonly experienced challenges.

Overcoming the barriers: training and education

Training and education by the community nurse is often the answer to overcoming internal and external barriers, although challenges related to the environment, especially outside of the home setting, can be difficult to address. Improving adherence and managing complications should be the main goals of the community nurse. Empowering the patient to choose the type of catheter most suited to their needs and lifestyle will improve adherence, as will an individualised, codified educational approach to training patients in the procedure. It is strongly recommended that the duration of patient training in ISC be adapted to the physical, cognitive and psychological capacities of the patient, as well as any patient-dependent environmental constraints (Balhi and Arfaoui, 2021). Each step of the catheterisation procedure should be shown to, and reiterated with the patient, including hand and perineum hygiene without an antiseptic, installation, location of the meatus and handling of the equipment (Balhi and Mrabet, 2020). Supplying patients with a basic knowledge of their anatomy may also be helpful to improving their understanding. Wherever possible, a nurse who has already established a therapeutic relationship with the patient should also teach them the ISC procedure (Ramm and Kane, 2011).