Managing the impact of prolonged bedrest in patients comprises a significant proportion of the community nurse's caseload. A patient may choose or require prolonged bedrest for a number of reasons, including injury, recovery from surgery, neurocognitive decline, disability, and age-related frailty or decreased mobility and difficulty in performing activities of daily living.

Prolonged bedrest can have harmful effects on both a patient's psychological wellbeing and physiological functioning. Just 10 days of bedrest has been found to result in a substantial loss of lower extremity strength, power and aerobic capacity, even in healthy older adults, and 20 days of bedrest was associated with the development of depression in a cohort of young, healthy adults (Ishizaki et al, 1994; Kortebein et al, 2008).

One of the primary areas of concern for the healthcare professional caring for individuals who are bedridden should be the patient's skin and soft tissue. In the absence of movement, pressure injuries can develop quickly-sometimes in only a matter of hours-especially in those with fragile skin or long-term chronic conditions, such as diabetes. These types of injuries pose a massive financial burden on the healthcare system and a substantial personal cost to affected individuals, because of their prevalence and severity. An incidence rate ranging from 4.5–25.2% has been approximated for the UK, with over 700 000 people affected by pressure ulcers each year across all care settings, including people in their own homes, at an estimated annual cost to the NHS of £1.8–2.6 billion (El-Saidy and Aboshehata, 2019).

The incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers increases with age, with over 60% of ulcers occurring in people aged over 70 years, which is likely owing to age-related skin changes or the fact that conditions causing immobility are more common in older people (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2024). Complications of pressure ulcers include:

Taking this into consideration, it is imperative for the community practitioner to be aware of the mechanisms, presentations and management strategies related to this common type of skin and soft tissue injury.

Understanding pressure injuries: a roadmap

Mechanisms of injury

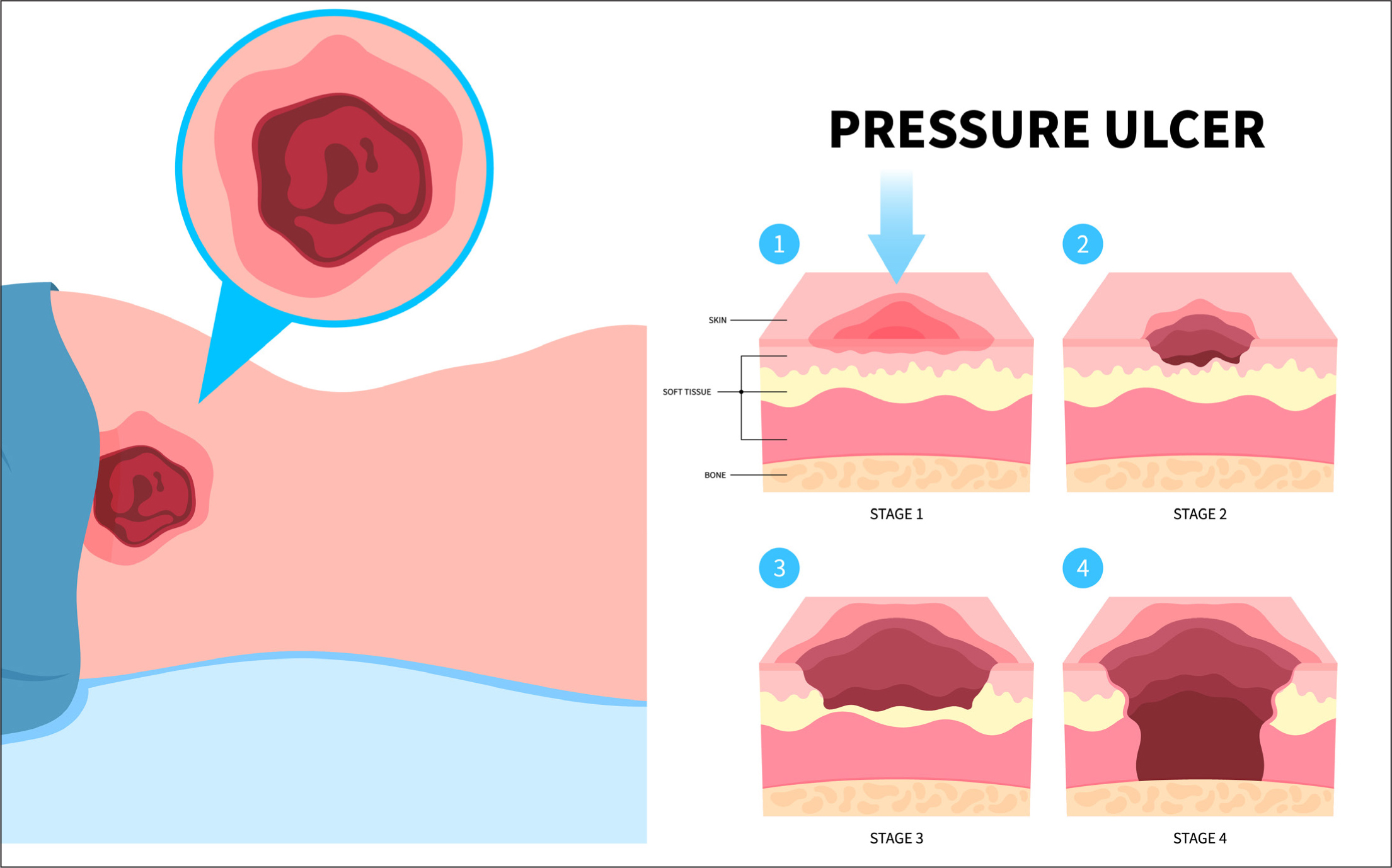

A pressure injury is defined as a soft tissue injury to a localised body part, which is caused by prolonged pressure and/or friction to the skin through extended periods spent in bed or use of a medical device (Mondragon and Zito, 2025). Pressure injuries commonly appear in bony areas of the body, such as the elbow, lower back and buttocks, inner knees and shoulders, and are exacerbated in patients with less body fat (Figure 1).

Presentation and assessment

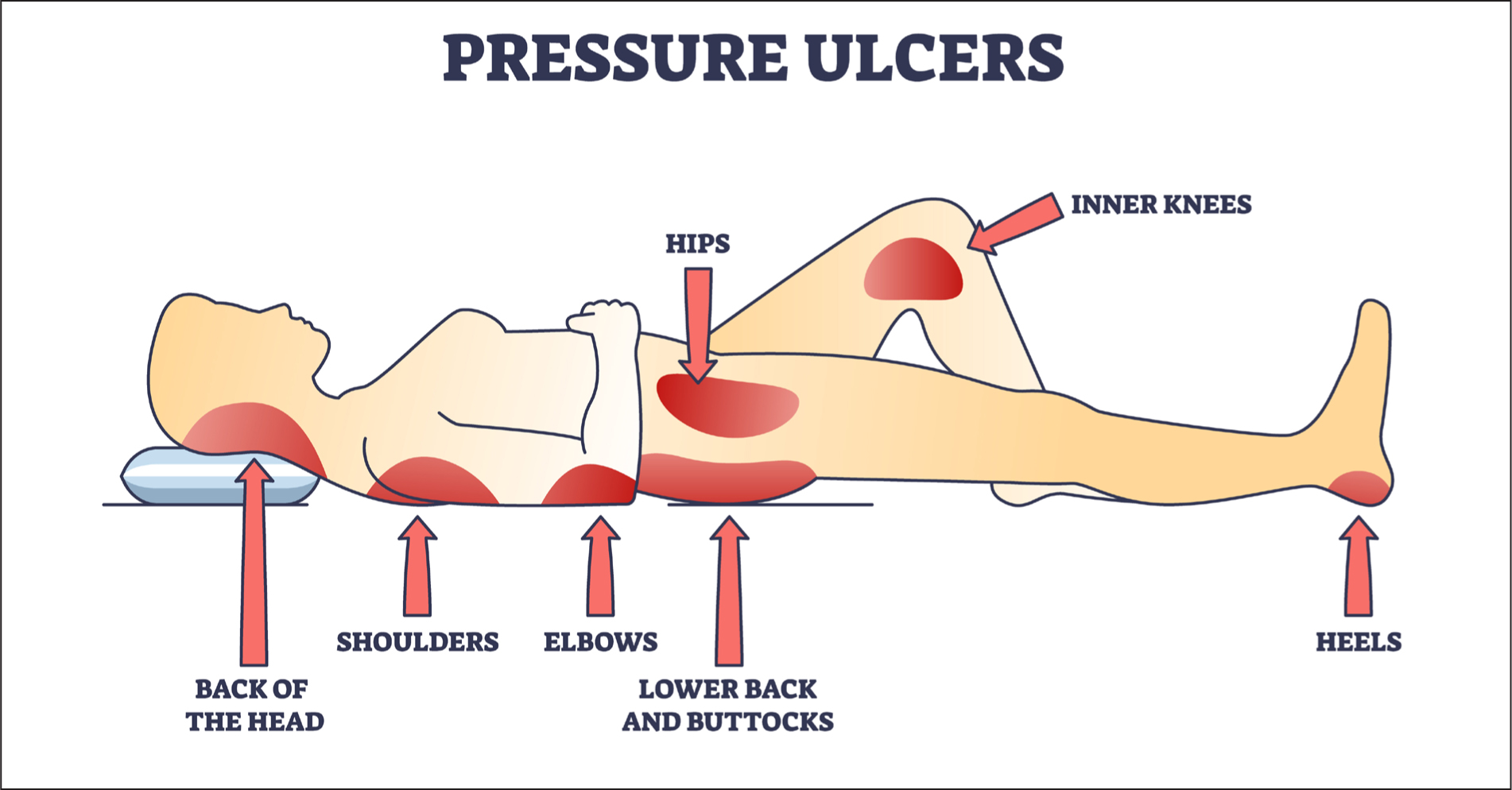

An underlying history of immobility (including, but not limited to, patients with bedridden status or who are chair-bound) is usually present; however, poorly fitting casts and medical equipment, devices and implants can also play a role (Mondragon and Zito, 2025). The superficial skin layer is less prone to be affected by pressure injury, so an overall physical examination may underestimate the extent of the damage. Minimal skin damage because of pressure may not necessarily be associated with ulceration. Moreover, deep tissue pressure injuries might occur without prominent overlying skin ulceration (Mondragon and Zito, 2025). In acknowledgement of these differing presentations, the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) has created a staging system to assist practitioners in identification of pressure injuries that may not adhere to clinical expectations of ulceration (NPIAP, 2016).

Strategies for success: preventing pressure sores in the community

Nurses play a pivotal role in the prevention, early detection and management of pressure injuries, given their frontline position in patient care. As primary caregivers, nurses are responsible for conducting regular skin assessments, implementing preventive measures and coordinating interdisciplinary interventions. Moreover, nurses serve as educators, advocates and leaders in promoting a culture of patient safety and empowerment within the community (Kandula, 2025).

In a revealing study by AlFadhalah et al (2024), conducted in Kuwait, the majority of national pressure injuries (58.1%) were found to be community-acquired, emphasising the need for increased focus on preventative measures and education outside of hospital settings. With their expertise, ability to leverage the therapeutic relationship and their intimate insight into patients' daily routines and care, community nurses are well-placed to make a real difference in pressure injury prevalence.

There are a number of management strategies associated with pressure injuries resulting from prolonged bedrest. General care for pressure injuries includes redistribution of pressure with the use of support surfaces and changes in patient positioning, both of which help reduce friction and shear forces.

Support surfaces include higher-specification foam mattresses, medical-grade sheepskins, continuous low-pressure supports, alternating-pressure devices and low-air loss therapy (Mondragon and Zito, 2025). Regarding repositioning, the optimum regimen for frequency and method of repositioning (for example, using tilt and/or lateral, supine, prone body position) is not yet standardised.

A Cochrane systematic review performed to assess the clinical effectiveness of different repositioning regimens found no clear evidence of difference in the risk of pressure injury development in patients who are repositioned every 2, 3 or 4 hours or between positioning using a 30° or 90° lateral position (Gillespie et al, 2020). The NICE (2014) recommend that patients at risk of developing pressure ulcers should be repositioned at least every 6 hours, with those at high risk repositioned at least every 4 hours.

Wound care also comprises a significant part of the pressure injury management toolkit. Maintaining a clean environment, debridement, application of dressings and careful monitoring are generally advised to facilitate the healing of pressure injuries (Mondragon and Zito, 2025). Stage 1 pressure injuries can be covered with transparent film dressings as needed; stage 2 injuries benefit from a moist wound environment through the use of occlusive dressings (foam, hydrogels and hydrocolloids) and non-occlusive dressings (transparent films). The treatment of stage 3 and 4 injuries is based on the presence of necrotic tissue and requires debridement (Mondragon and Zito, 2025) (Figure 2). The NICE (2014) recommend the use of autolytic debridement, using an appropriate dressing to support it, with sharp debridement to be used if autolytic debridement is likely to take longer and prolong healing time.