Many people think that medicines are prescribed with great care by experienced staff; this is not always the case. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that ‘more than half of all medicines are prescribed, dispensed or sold inappropriately, and that half of all patients fail to take them correctly’ (WHO, 2022). Medicines can harm as well as heal. The greater the number of medicines prescribed, the greater the risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and incorrect medicine consumption. This article outlines why older people are at greater risk of adverse drug reactions, how to work with the older person to review medicines and the benefits of medication reviews.

How ageing increases the risks of adverse drug reactions

Adverse drug reactions are ‘unintended, harmful events attributed to the use of medicines’ (Coleman and Pontefract, 2016). Ageing affects the body's ability to absorb and excrete medicines and increases the risk of harmful effects. Each organ and system in a young person's body has a substantial reserve capacity available to deal with high-demand or high-stress situations. As people age, this reserve capacity diminishes (Milanović et al, 2013). Aerobic capacity, the body's ability deliver oxygen to the muscles, decreases by 30% from the age of 40-65 years and muscle mass reduces by 30-50% between the age of 30 and 80 years.

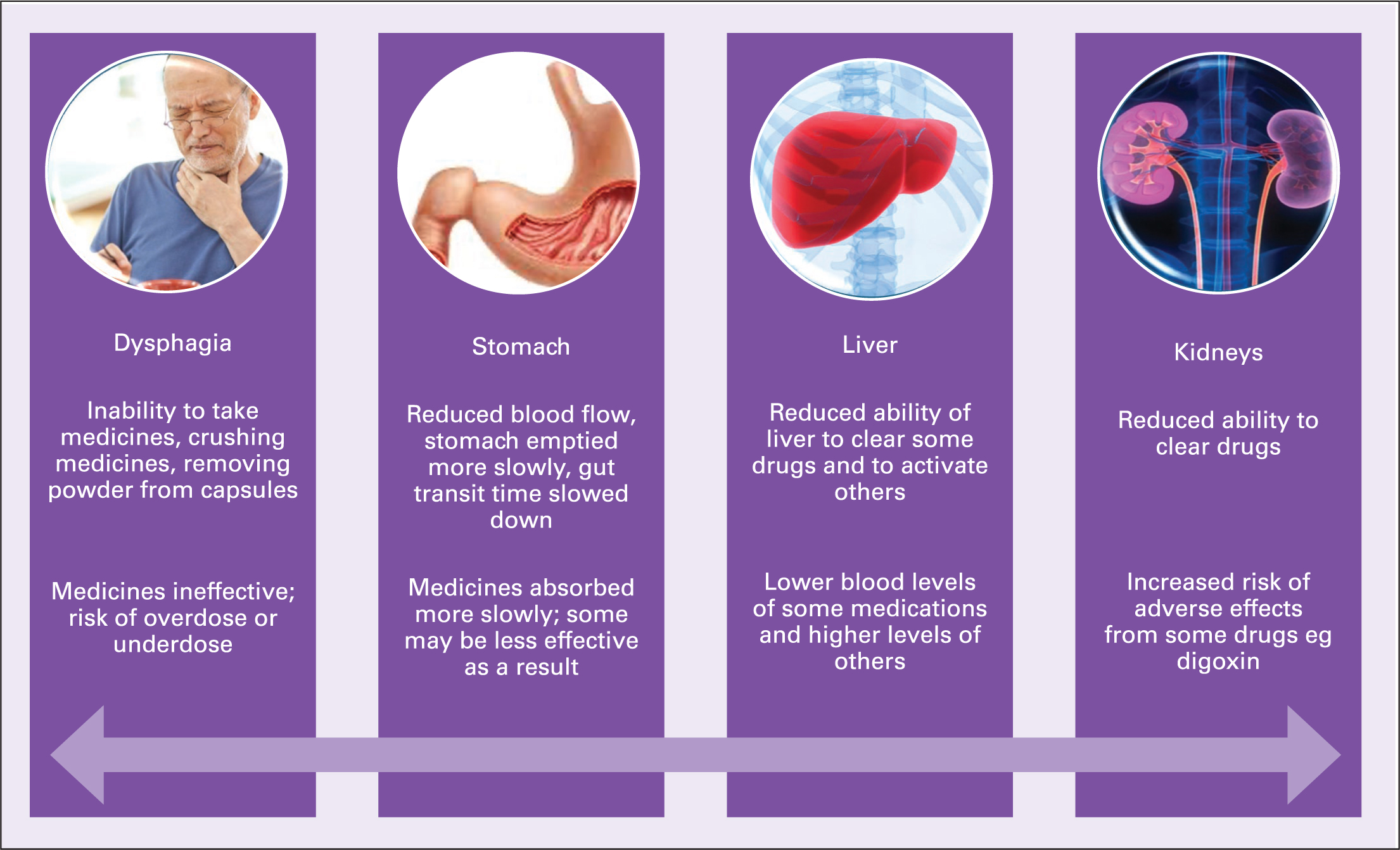

Adults lose 12-14% of muscle strength per decade after the age of 50 and the person's reserve capacity also declines (Hatheway et al, 2017). This loss of reserve affects the older individual's ability to adapt to problems caused by medication. Age-related changes also affect how the body reacts to medicines. Figure 1 provides an overview of reasons why older people are vulnerable to adverse effects of medication.

Age-related changes

Oral medicines are swallowed, absorbed in the small intestine, metabolised in the liver and excreted by the kidneys (Garza et al, 2022). Age-related changes can affect the ability to swallow medication; this is crucial because if a person already has dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), they may omit the medicine, crush it or open the capsule. A survey of 791 older people attending 17 community pharmacies, carried out by pharmacists, found that nearly 60% of them had difficulty swallowing medication and reported opening tablets and crushing medication.

Older people were asked if they had informed their General Practitioners, and 72% reported that they had not been asked (Strachan and Greener, 2005). Dysphagia becomes more common as people age and become frail (Smithard, 2015; Cohen et al, 2021). Medication absorption is affected by reduced blood flow to the gastro-intestinal tract because of delayed stomach emptying and delayed gut transit times (Dumic et al, 2019). As people age there is a decline in muscle mass and an increase in fat; this affects the way medicines are absorbed (Distefano and Goodpaster, 2018). Blood flow to the liver is reduced by 40% and the liver shrinks by 20%; these changes reduce the body's ability to metabolise drugs.

There are increased plasma concentrations of some drugs such as morphine, verapamil and propranolol, and decreased levels of others such as prednisolone and clopidogrel, because of the liver's reduced ability to metabolise (Drenth-van Maanen et al, 2020). Many medicines are excreted from the body through the kidneys, however, renal function declines with age and this can impair the body's ability to excrete medication (Fang et al, 2020).

Age-related changes at a molecular level can alter the way drugs bind to specific receptors and it can increase or decrease the effect of a medicine in an older person. These age-related changes affect the way an older person's body reacts to medication. They may no longer require a certain medication, may need different medicines or different doses of the same medication. Figure 2 summarises these changes.

As people age, their chances of develop long-term conditions increase and they require medication to treat these conditions (Bennett et al, 2021). Although older people are most likely to require medicines to treat a range of conditions, including hypertension and cardiac problems, most drugs are tested on younger people. Older people are under-represented in clinical trials. This means that the efficacy of a drug and the side effects noted may differ in older people and in those belonging to racial and ethnic minorities and low-income communities (Fisher et al, 2022).

What is polypharmacy?

While there is no standard definition, polypharmacy is often described as the routine use of five or more medications. WHO (2022) considers it helpful to examine the appropriateness of medicines rather than their number.

It comments:

‘Rational use of medicines requires that patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and their community.’

The hazards of polypharmacy include ADRs, prescribing high-risk medications and the use of the prescribing cascade. Inappropriate prescribing can have a major impact on a person's quality of life, leading to emergency hospital admission and an increase in bed pressures and NHS costs. The number of emergency admissions because of ADRs and the number of bed days used are constantly increasing (Veeren and Weiss, 2017). A study of medical admissions found that 16.5% of all admissions in a month (n=218) were the result of an ADR. Extrapolated nationally, the projected annual cost to the NHS in England is 2.21 billion (Osanlou et al, 2022). It is important that clinicians who care for older people are fully aware of the impact medication can have on a person. Case history 1 demonstrates this point.

Case history 1

Mrs Alice Evans is a 92-year-old woman. She is severely frail and bedbound. Mrs Evans has cancer, epilepsy and hypothyroidism. She is on a palliative care pathway and has a do not attempt resuscitation order in place. The aims of care are to promote comfort for Mrs Evans, not for any active treatment. Mrs Evans became very drowsy and started vomiting. She was admitted to the hospital and found to have severe hyponatraemia; her serum sodium concentration was 116 mmol/L. Mrs Evans was taking the following medication:

- Omeprazole, 20 mg each morning

- Folic acid, 5 mg each morning

- Levetiracetam, 500 mg each morning

- Levothyroxine, 75 mcg each morning

Medical staff discontinued omeprazole as it can cause severe hyponatraemia (Falhammar et al, 2019). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020) guidance recommends that medication causing hyponatraemia should be discontinued and sodium should be rechecked in two weeks. Medical staff prescribed famotidine, 20 mg daily. This H2-receptor antagonist is given for 6–8 weeks to treat benign gastric and duodenal ulceration. It can increase the risk of seizures (British National Formulary (BNF), 2024a).

What could have been done better?

Mrs Evans has been treated with omeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), for many years. Her medical records do not provide information about why it was initially prescribed. Mrs Evans has no recorded history of gastrointestinal bleeding, oesophagitis or any other licensed indication. Generally, PPIs are given for eight weeks unless there are indications, such as prophylaxis in patients with a history of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-(NSAID) associated gastroduodenal lesions and require continued NSAID treatment (BNF, 2024b). Mrs Evans would have benefitted from a further medication review in primary care. Had the omeprazole been discontinued, she would have been spared a distressing hospital admission. On admission to the hospital, Mrs Evans would have benefitted from a careful review of her medication. It may have shown a lack of a clear indication for omeprazole. The prescriber may have discontinued the omeprazole without prescribing famotidine and asked primary care to monitor Mrs Evans and recheck sodium.

The importance of medicine reviews

Older people are especially vulnerable to adverse effects from medication including drowsiness, increased risk of falls, increased risk of hospital admission and reduced quality of life. NHS England (2020) recommends medication reviews for people on 10 or more medicines; living in care homes; with frailty; who have had recent hospital admissions, especially for falls.

Working with the older person to carry out a medication review

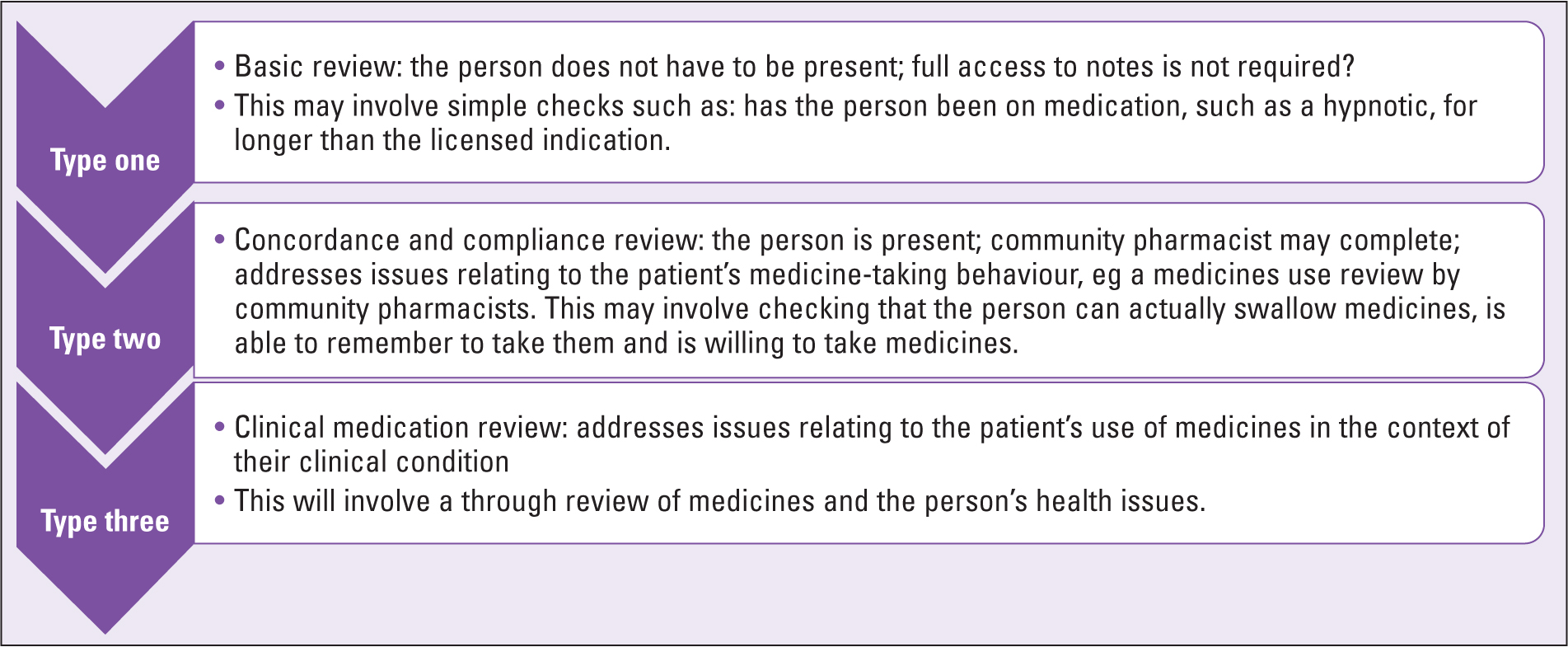

The National Prescribing Centre advises that there are three types of medication reviews (Figure 3): type one, a prescription review; type two, a concordance and compliance review; type 3, a clinical medication review (Clyne et al, 2008).

While it is important to work with older persons, research indicates that medicine reviews may be carried out without involving the patient (Duncan et al, 2019). The aim of a medication review is to ensure that the person is prescribed appropriate medicines that minimise the risk of adverse effects and improve quality of life. Box 1 provides key questions to guide the review.

Box 1.

Questions to guide the medicines review

| How are you getting on with your medications? |

| Are there any medicines that you find difficult to take? |

| Do you think that you are having side effects from the medicines? |

| What medicines do you want to stop the most? |

| Why do you want to stop these medicines? |

| Do you have any symptoms that are not being addressed by the medicines you are taking? |

| What symptoms do you want treated the most? |

Medication review should be a conversation between the prescriber and the individual about shared decisions regarding treatment and care. The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AOMRC) (2020) advocates a collaborative process in which healthcare professionals work together with patients to select tests, treatments and care management or support packages, based on clinical evidence and the person's informed preferences and values. This clearly acknowledges that there is usually more than one way to treat a problem, including ‘no treatment’, and patients may require help to weigh the benefits and risks of the options to determine the best choice for them. Evidence indicates that shared decision-making benefits patients, improving the quality and appropriateness of clinical decision making. The AOMRC (2020) recommend the use of BRAN—a tool to guide the conversation at a medication review, which was used in Case history 2. This consists of four questions:

- What are the Benefits?

- What are the Risks?

- What are the Alternatives?

- What if I do Nothing?

Case history 2

Mr Jon Singh is a 68-year-old man. He weighs 98 kg and has a body mass index of 32. He has recently lost 10 kg. Mr Singh has type 2 diabetes, elevated cholesterol and hypertension. His diabetes control is improving and his cholesterol is now within the normal range. Mr Singh is not keen on taking medicine for his blood pressure. ‘I am taking a ton of tablets and you have put me on a diet. I am not keen on taking more tablets. What are the benefits—I feel perfectly fine, I am not having headaches or anything.’

Benefits: reduced risk of stroke by 27%, coronary heart disease by 17%, reduction of heart failure by 28% and reduction in all-cause mortality by 13% (Agyemang et al, 2015)

Risks: side effects include dizziness, cough and runny nose

Alternatives: lose more weight, give up smoking and reduce salt in diet

Nothing: increased risk of ill health which should be monitored

Mr Singh wrote down the name of the proposed medication, ramipril and the dosage 1.25 mg, and said he would look this up and make a further appointment. Two weeks later he visited. He said he'd bought a blood pressure machine and realised that his blood pressure was on the higher end. He agreed to start a small dose of ramipril to be up-titrated over the course of a year.

Sometimes the older person may decline to take a medicine because of fear of side effects. The medication review enables the prescriber to have a dialogue with the patient. Case history 3 provides an example of this.

Case history 3

Mrs Andrea Chisholm is a 72-year-old woman. She weighs 102 kg, has a body mass index of 38, is hypertensive, has high cholesterol and was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes 4 months ago. Mrs Chisholm was referred to a dietician and prescribed metformin 500 mg daily, with instructions to increase this to twice daily and then to 1 g twice a day (Skugor, 2017). Her glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 90 mmol/mol, indicative of poor diabetes control. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2022) recommends that people with diabetes should be supported to achieve an HbA1c level between 48–53 mmol/mol.

Mrs Chisholm reports that she has not been taking her metformin. She says it should never have been prescribed and that she was given no warning of the side effects. The most common side effects of metformin are diarrhoea, nausea, abdominal discomfort and a metallic taste in the mouth. These side effects often resolve with continued use. Mrs Chisholm had an episode of diarrhoea while shopping and was incontinent of faeces, saying ‘I was mortified. I am never taking that again.’ Medication review enabled the prescriber to establish a dialogue with Mrs Chisholm, to rebuild trust and to begin effective treatment for Type 2 diabetes. Mrs Chisholm was prescribed an SGLT2, dapagliflozin 10 mg each morning, and reviewed regularly. She experienced no further adverse effects and her blood glucose levels gradually stabilised.

Tools to guide medication reviews

There are a number of tools available to help prescribers review medication. The STOPP/START tool is based on a literature review and expert opinion from 13 European countries. It aims to alert prescribers to medications that are inappropriate (STOPP) and has a screening tool to alert to right treatment (START) (O'Mahoney et al, 2015).

The authors stated that all drugs should be clinically indicated and must outline the criterion for discontinuation. Box 2 provides details of the broad criterion for discontinuation of medication. In 2021, the STOPPFrail version 2 was introduced to provide clinicians with an up-to-date evidence-based approach to deprescribing decisions in older people with limited life expectancy (Curtin et al, 2021).

Box 2.

STOPP/START broad criterion for discontinuation of medication

| Any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication. |

| Any drug prescribed beyond the recommended duration, where treatment duration is well defined. |

| Any duplicate drug class prescription eg two concurrent NSAIDs, SSRIs, loop diuretics, ACE inhibitors, anticoagulants (optimisation of monotherapy within a single drug class should be observed before considering a new agent). |

Cholinergic burden

Medicines with anticholinergic properties work by blocking the action of acetylcholine, which is a neurotransmitter. Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers in the brain. Anticholinergic medications are used to treat Parkinson's disease, hypertension, abnormal heart rhythms, depression, bladder problems and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Arthur et al, 2020). Medicines have different levels of anticholinergic effect and the cumulative anticholinergic effect of all the medications a person takes is known as the ‘cholinergic burden’. High levels of cholinergic burden are associated with an increased risk of dementia and mortality (Coupland et al, 2019; Taylor-Rowan et al, 2022). The ABC tool enables clinicians to work out the cholinergic burden of an individual's medicines.

Adverse effects of anticholinergics include dry mouth, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, vomiting, constipation, abdominal pain, urinary retention, blurred vision, tachycardia and neurologic impairment, such as confusion and agitation. Anticholinergic medication can cause daytime drowsiness, cognitive decline, increase the risk of falls and lead to increased mortality (Taylor-Rowan et al, 2022; Bishara, 2023). Although anticholinergic medications should be avoided whenever possible, in older people the use of anticholinergics has almost doubled in the last 20 years and those who are most vulnerable to adverse effects have had the greatest increase in use (Grossi et al, 2020).

The benefits of medication reviews

Medication reviews can make a huge difference to the lives of older people, especially those who are vulnerable. They can identify problems encountered while taking medication, such as difficulty swallowing large tablets or forgetting to a take a weekly tablet. The review can identify issues regarding compliance. The person might, for example, not be taking medicine for hypertension because of side effects like postural hypotension or polyuria. The review enables the prescriber to check blood pressure, evaluate medication, discontinue what is not needed and change medication as necessary. These actions ensure that conditions are treated and adverse effects are minimised. This reduces the risk of falls and hospital admission (Liew et al, 2019).

Conclusions

The UK's population is ageing and an increasing number of older people are living with multiple long-term conditions, and are therefore vulnerable to the adverse effects of polypharmacy. It is important that all nurses consider non-pharmacological means to treat certain conditions. If a person has constipation, it is better to advise on fluids and diet, and promoting a normal bowel habit, rather than simply considering laxatives. Prescribers should prescribe with care and review medication; if a medicine, such as a hypnotic or a proton pump inhibitor, is licensed for short term use, it should be changed after a while instead of prescribing off-license.

Medication should be reviewed when there are concerns about a person's health and well-being because of a fall or hospital admission. A holistic approach can ensure that treatment is optimised and risks of adverse drug reactions are reduced so that the older person can enjoy the best possible quality of life.

Key points

- The number of older people taking five or more medications has quadrupled in the last 20 years.

- The use of anticholinergic medicines has doubled, despite the heightened risks of adverse effects.

- Inappropriate prescribing is relatively common.

- Age-related changes increase vulnerability to the adverse effects of medication.

- Polypharmacy increases the risks of adverse drug effects, such as falls and hospitalisation.

- Medication reviews can improve the treatment of long-term conditions and enhance quality of life.

CPD reflective questions

- How often do you think an older person should have a medicines review? What would you take into consideration when determining the frequency of review?

- Mrs James has hypertension. She is prescribed amlodipine 10 mg each morning and verapamil 80 mg three times a day. She is not taking either. She says the amlodipine caused her legs to swell and the verapamil gives her headaches and makes her feel dizzy and sick. What would you do and why?

- Will you change your practice after reading this article? If so, how?