Poor oral health is recognised to have an adverse effect on the overall health of a person. Therefore, it is important that all health professionals strive to provide holistic patient care, including maintenance of oral health, in order to optimise patient outcomes. This is particularly important within the community, where nursing teams are often responsible for caring for vulnerable and older patients with complex medical histories. The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) (2010) highlighted the importance of prioritising oral health within a patient's overall care plan, acknowledging that the level of oral hygiene can act as an indicator of the standard of care a patient is receiving.

Part 1 of this mini-series (Archer et al, 2020) discussed the common oral conditions that community patients may present with, as well as the role of the nursing team in aiding the prevention, diagnosis and management of these conditions. This article explores the complications that can arise with systemic diseases as a result of poor oral health and discusses how community nursing teams can support oral care and therefore prevent these systemic complications.

How oral health is linked to general health

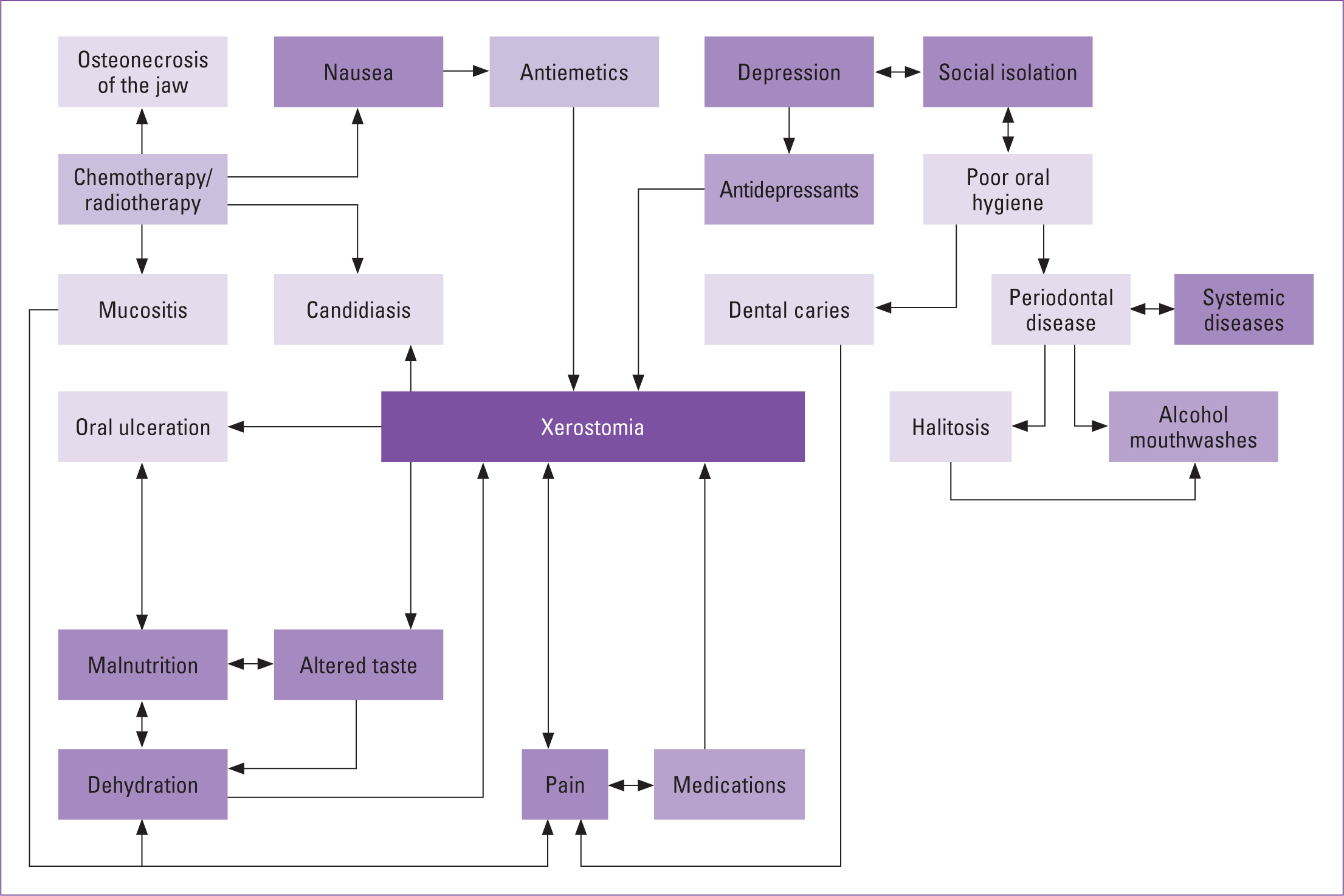

The oral cavity acts as a focal point for the interaction of the body with the external environment, with its key functions including mastication, taste, speech and swallowing (Kane, 2017). Alteration to these functions can negatively impact on function and quality of life and hamper psychological and social wellbeing. Figure 1 outlines the complex relationships that exist between oral health, systemic disease and psychological wellbeing.

Figure 1. Complex relationship between oral issues and systemic associations

Figure 1. Complex relationship between oral issues and systemic associations

While understanding that the primary focus for dentists is oral health, awareness of the systemic complications that can arise from oral pathology is also paramount. Equally, it is important that education on the impact of oral health on general health is provided for medical and nursing professionals. With such significant demands placed on nurses for their time and expertise, it has been demonstrated that oral care is deemed a low priority when compared with other clinical tasks (Wardh et al, 2000). Patient care will benefit if medical and nursing professionals are actively encouraged to prioritise oral care in accordance with other areas of general healthcare.

The link between periodontal (gum) health and systemic health has been extensively researched, with the chronic inflammatory pathogenesis of periodontal disease shown to be associated with increased haematological inflammatory markers (Bretz et al, 2005). Poorly managed periodontal disease has been demonstrated to have an adverse effect on diabetes control and to increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD). The main systemic health complications that arise as a result of poor oral health are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Systemic health complications of poor oral health

| Systemic disease | Link to oral health |

|---|---|

| Diabetes |

|

| CVD |

|

| Aspiration pneumonia |

|

| Infective endocarditis |

|

| MRONJ |

|

| Dementia |

|

Oral health and malnutrition

Malnutrition affects approximately 3 million people in the UK, with approximately 93% living in the community (Murphy et al, 2018). The systemic effects of malnutrition include impaired cardiac and respiratory function, muscular weakness, depression, poor quality of life, worsened response to radiation or chemotherapy and increased postoperative complications (Talwar et al, 2016). Malnutrition can also be detrimental to oral health, because it increases the prevalence and severity of candidal infection, mucositis, oral ulceration, tongue alterations and low saliva flow (Andersson et al, 2004). This is particularly notable in the older population, where hyposalivation, impaired taste sensitivity and reduced masticatory function have been shown to lead to undernutrition and weight loss (Kossioni, 2018). These conditions can also result in oral pain, which can subsequently further worsen nutritional intake.

Ageing is associated with loss of teeth, xerostomia, periodontal disease, dental caries, painful mucosal conditions and decreased masticatory function. These conditions can all influence a person's chewing ability, taste perception and capacity to swallow, resulting in weight loss, low BMI and malnutrition (Peterson and Yamamoto, 2005; Kossioni, 2018). A systematic review by van Lancker et al (2012) further identified masticatory problems as an independent predictor of low BMI and serum albumin levels, weight loss and protein energy malnutrition.

Oral cancer is a multifactorial malignancy, with risk factors including tobacco usage, alcohol intake, human papilloma virus and micronutrient deficiency (Petti, 2009). Some 80% of patients with head and neck cancers are malnourished prior to treatment, because of these associated lifestyle and risk factors (Müller-Richter et al, 2017). Treatment for head and neck cancers can include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, all of which can result in xerostomia and loss of taste. Kossioni (2018) highlighted that patients experiencing taste difficulties are 2.5 times more likely to be malnourished, which is disadvantageous in patients with cancer, who may already be nutritionally deficient. Appropriate multidisciplinary support and regular review of nutritional intake and weight maintenance is essential in this vulnerable patient group.

Sheiham and Steele (2001) reported that the daily intake of non-starch polysaccharides, protein, calcium, non-haem iron, niacin, vitamin C and intrinsic and milk sugars was significantly lower in patients with no teeth. There is also increasing evidence that the use of dentures when provided with ongoing tailored nutritional advice may improve the nutritional status of patients, with studies demonstrating an increase in fruit and vegetable consumption with simultaneous denture provision and dietary counselling (Bradbury et al, 2006; Kossioni, 2018). The consumption of fruit and vegetables was seen to decrease over time when no input was provided (Bradbury et al, 2006; Kossioni, 2018).

Dentures and nutritional intake

With an ageing population, patients are retaining their teeth for longer than they have done historically. The Adult Dental Health Survey in 2009 (NHS Digital, 2010) showed that 6% of the population older than 65 years are edentulous (have no natural remaining teeth) compared with 37% in 1968 (Murray, 2011). For patients who have experienced tooth loss, pain may also be a result of ill-fitting dentures. Rodrigues et al (2012) found that tooth loss was the biggest nuisance to older study subjects (57.6%), followed by the use of dentures (30.3%) and ill-fitting dentures (33.3%). Poorly fitting dentures can cause pain and discomfort and may also lead to angular cheilitis, a candidal infection where one or both corners of the mouth become erythematous, inflamed, crusted and cracked (Health Education England, 2016). While pain from ill-fitting dentures may have an impact on a patient's ability to eat and lead to weight loss, weight loss also can contribute to dentures becoming loose. It is, therefore, important to review and consider the use of dentures when completing a Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) assessment. Figure 2 demonstrates the different types of dentures available.

Figure 2. Types of dentures. (A) Partial dentures (replacing some missing teeth). (B) Complete dentures (replacing all missing teeth)

Figure 2. Types of dentures. (A) Partial dentures (replacing some missing teeth). (B) Complete dentures (replacing all missing teeth)

Patients with new dentures, particularly those who have never worn dentures before, will need time for the musculature to adapt to the new prostheses, which can have an effect on oral intake. Box 1 outlines the nutritional advice that can be given to patients who have been provided with new dentures.

Box 1.Nutritional advice for patients within the first few days of receiving new dentures

- Small amounts of soft food should be placed on both sides of the mouth

- Avoid hard, sticky or chewy foods

- Prepare foods where possible, by cutting into small pieces or mashing

- Expect an element of discomfort during the adaptation stage

- Ensure you wear your denture the day before a dental appointment, so the places where the denture would benefit from adjustment can be identified

Adapted from Kossioni, 2018

Assessing the oral health needs of a patient

Completion of a simple oral health assessment should form part of a patient's overall care plan. For patients in care homes, it is essential that an oral care regime is established as part of an oral care plan, with provision of the necessary additional support to maintain good levels of oral hygiene (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2016).

History-taking can aid identification of oral risk factors that may have an impact on a patient's general health, including glycaemic control and barriers to oral intake. Inclusion of family members and carers in these discussions may be beneficial. Recording the details of the patient's dentist is useful and can facilitate ease of contact should dental advice be required in the future. It is important that patients maintain contact with their own dentist, particularly if they have not been seen for 12 months. Edentulous patients should still have assessments by a dentist to assess oral cavity tissues and any existing prostheses (Oral Health Foundation, 2018). A summary of oral health considerations is provided in Box 2.

Following an oral health history, it would be prudent to perform a brief intraoral assessment alongside general health and physical examination. This should involve looking at the patients lips, tongue, teeth and gums, cheeks and dentures, and be documented as a baseline for other professionals to refer back to in future if required. Nursing teams may also recognise whether the oral health of the patient could be adversely contributing towards the patient's general health, for example, ill-fitting dentures contributing towards loss of appetite and malnutrition.

Accessing a dentist

In the UK, the cost of NHS dental treatment is divided into three bands, with some patients entitled to discounted or free NHS treatment depending on their medical and social circumstances. For patients who do not have a dentist, the NHS Choices website and 111 telephone support can help identify local dental practices who are accepting new NHS patients for routine and urgent dental care (NHS, 2020).

Specialist dental services exist for patients who may be unable to attend their dental practice due to a disability or medical condition. Community and hospital dental services (special care dentistry) provide treatment in hospitals, specialist health centres and mobile clinics, as well as domiciliary visits to patient homes, and nursing homes (British Society for Disability and Oral Health, 2020a; 2020b). Referral criteria vary across different trusts, with some trusts allowing community nursing teams to refer patients directly to their local specialist service, as long as they fulfil the acceptance criteria. Nurses must also be encouraged to seek advice and support from a patient's dentist if they have concerns they wish to express.

Box 2.Consideration of oral health needs

- Does the patient have any oral pain or discomfort?

- Does the patient have their own dentist? When was their last visit?

- Who carries out oral care for the patient? (e.g. independent, family)

- What equipment is used to complete patients oral hygiene regime? (e.g. toothbrush, floss)

- Does the patient wear dentures?

- Does the patient have xerostomia?

- Does the patient have any medical conditions that put them at increased oral health risk (e.g. chemotherapy, radiotherapy, learning difficulties, palliative, cognitive function impairment)?

- Does the patient have any physical restrictions that may limit their ability to carry out basic oral care (e.g. osteoarthritis)

Further resources for nursing teams

Recognising the importance of oral health on the general health and wellbeing of patients is important for all health professionals. Some resources available (such as Mouth Care Matters (Health Education England (2016)) include additional online training for members of the community nursing teams to complete.

Conclusion

Promotion and maintenance of oral health is the responsibility of all health professionals, not just the dental team. The links between oral and general health are well established, and simple preventative measures supported by community nursing teams can help to minimise serious long-term systemic complications for patients later on.

KEY POINTS

- Oral health can significantly impact on the systemic health of people

- Supporting health professionals' education in oral health can help prevent oral disease and subsequent deterioration in systemic health

- Both patients and nurses will benefit from learning how to assess oral health needs and how to access dental intervention

CPD REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- What systemic conditions can be exacerbated by poor oral health?

- What oral care support can nurses provide to prevent the negative impacts of poor oral hygiene?

- What additional resources are available to nurses for further information on supporting oral care?