Medieval barber-surgeons operated with primitive instruments and without anaesthesia or aseptic technique, let alone effective antibiotics. Popular medieval wound dressings included ground rabbit fur and powders made from the remains of Egyptian mummies. Not surprisingly, postoperative mortality reached 60–80% usually from ‘hospital’ (Streptococcal) gangrene (Smith et al, 2012).

Instruments and techniques improved over the centuries. The famous Victorian surgeon Robert Liston could amputate and suture a leg in about 30 seconds. Liston's postoperative mortality rate, based on 66 amputations he performed at University College London Hospital between 1835 and 1840, was 1 in 6. Around the same time, mortality following amputations was 1 in 4 at St Bartholomew's Hospital (Thomas, 2012).

Liston also holds an unenviable record: a 300% mortality rate after one amputation. In addition to the patient's leg, Liston amputated his assistant's fingers. The assistant and patient died from infection. Liston also sliced through an observer's coat tails. The man thought Liston had cut him and died from shock (Thomas, 2012).

Today, surgeons use robots to perform intricate surgery, sophisticated dressings promote wound healing, while antibiotics and addressing procedural risk factors (Table 1) help reduce surgical site infections (SSIs) and postoperative deaths. A retrospective analysis of 50000 adults who underwent open surgery between 2017 and 2022 reported a mean overall 30-day mortality rate of 1%. Mortality increased to 3% after emergency high-risk procedures and following vascular surgery (Guest et al, 2023).

Table 1. Risk factors associated with increased surgical site infections

| Patient-related | Procedural |

|---|---|

| Age* | Airbourne contamination |

| Diabetes | Anticoagulation |

| History of radiotherapy* | Blood transfusions |

| History of skin and soft tissue infections* | Decreased oxygenation of tissues |

| Immunosuppression (drugs and conditions) | Foreign material |

| Malnutrition | Operation duration |

| Obesity | Perioperative hypothermia |

| Preoperative infections | Postoperative hyperglycaemia |

| Tobacco use | Surgical technique |

| Wound care | |

| Wound contamination (patient's flora operating room personnel; surgical instruments) |

Non-modifiable risk factor. Adapted from Seidelman et al (2023)

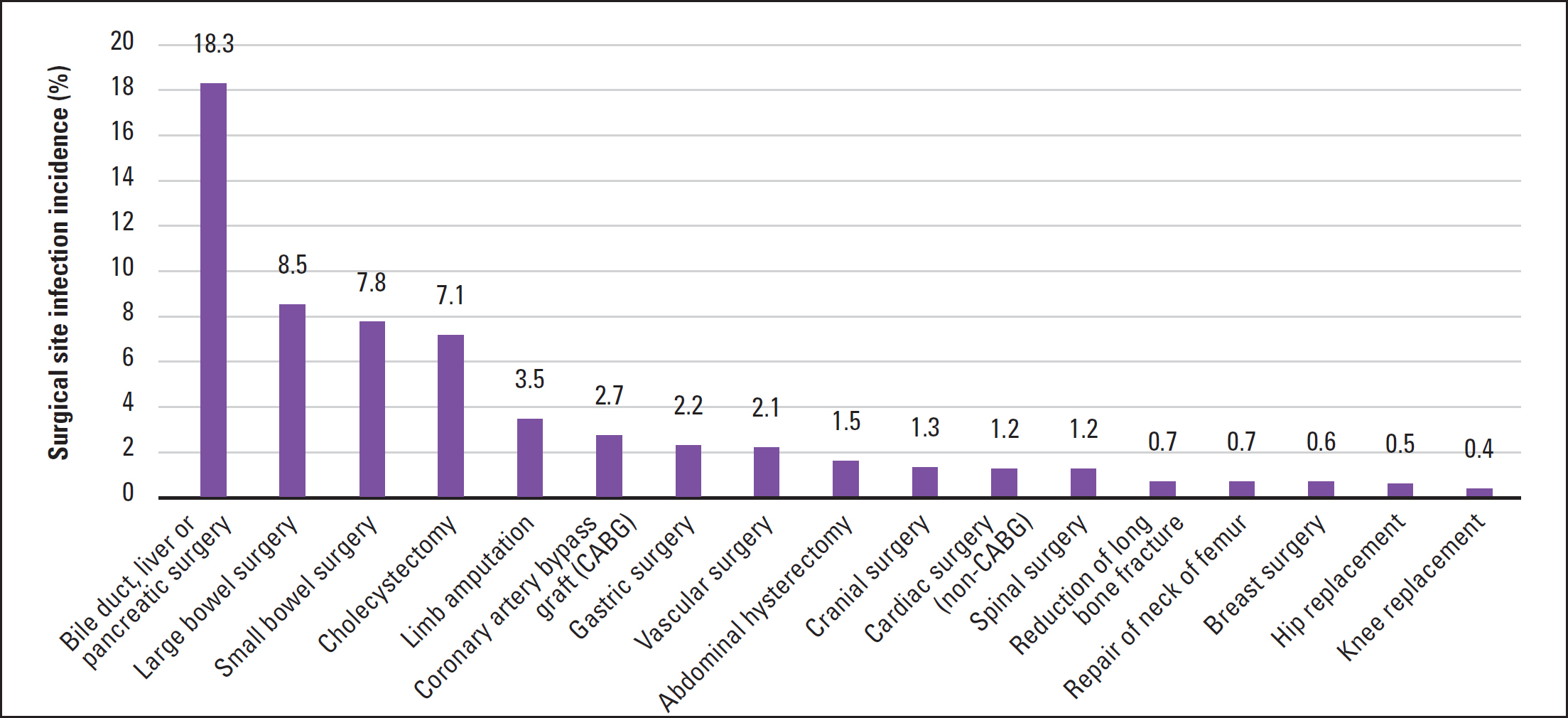

Nevertheless, rates of SSIs have improved little over recent years, despite measures to prevent infection (Long et al, 2024). The analysis of 50 000 adults who underwent open surgery reported that 11% of patients developed an SSI (Guest et al, 2023). According to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) in 2022–23, bile duct, liver or pancreatic cancer (18.3% of patients contracted an SSI) and bowel surgery (large bowel: 8.5%; small bowel: 7.8%) carried the highest risk of SSIs in NHS hospitals in England (UKHSA, 2023). Hip and knee replacement had the lowest risks (0.5% and 0.4%, respectively) (Figure 1). This pattern reflects the higher risk of bacterial contamination during abdominal surgery than orthopaedic surgery (UKHSA, 2023).

The drive towards shorter in-patient admissions means that many SSIs emerge in the community. In the analysis of 50000 adults, 85% of SSIs developed after discharge, on average 18.4 days after surgery. The proportion developing SSIs in the community ranged from 67% after vascular surgery to 90% following obstetric and gynaecological procedures (Guest et al, 2023).

The UKHSA notes that admissions for knee or hip replacement, breast, spinal and vascular surgery and abdominal hysterectomy typically last up to 3 days. However, the median time for infections was 24 days (knee) and 22 days (hip replacement), 17 days (breast), 15 days (spinal) and 14 days (vascular) surgery and 11 days (abdominal hysterectomy) (UKHSA, 2023). So, practice and district nurses tend to manage SSIs (Guest et al, 2023).

Antimicrobial resistance

Despite relatively low postoperative mortality, some iatrogenic bacteria showing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remain deadly. For example, Acinetobacter baumannii causes serious nosocomial infections such as ventilator-associated pneumonia, urinary tract, catheter-related bloodstream and wound infections, as well as SSIs (Du et al, 2019; Castanheira et al, 2023; Lucidi et al, 2024). Mortality from invasive carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) infections can reach 40–60% (Zampaloni et al, 2024). Carbapenems are typically used when other antibiotics have failed.

To reduce SSI risk, patients may receive prophylactic antibiotics before surgery, which exert strong selection pressure on bacteria. Strains, such as CRAB, harbouring genes that confer resistance to the antibiotic survive (Santos-Lopez et al, 2021). Nevertheless, antibiotic doses above the minimum inhibitory concentration (the lowest antibiotic concentration that completely suppresses bacterial growth) have a 99% chance of clearing the infection (Santos-Lopez et al, 2021). However, introducing only 100 colony-forming units of bacteria into the surgical site can cause an SSI (Seidelman et al, 2023). So, even small populations that escape the antibiotic can reinfect the patient (Santos-Lopez et al, 2021).

SSIs can also develop from the trillions of bacteria, fungi and other micro-organisms on our skins, gastrointestinal tracts, genitals and other body niches (Kennedy, 2024; Seidelman et al, 2023). Our bodies are home to 40 trillion bacteria and at least 400 trillion viruses. The human microbiome weighs about the same as our brains: 1–2 kg (Kennedy, 2024). Usually these ‘endogenous bacteria’ are harmless, even beneficial. Nevertheless, inoculation by endogenous bacteria causes about 70–95% of SSIs (Seidelman et al, 2023).

A recent study analysed the genomes of bacteria from 204 adults undergoing posterior spinal fusion. A total of 14 patients (6.8%) developed SSIs. The SSI rate among another 1406 patients who underwent lower-risk and minimally invasive surgery was 4.2% (Long et al, 2024). Among adults undergoing posterior spinal fusion, 86% of isolates from the SSI closely matched a strain present in one or more faecal, nasal or rectal samples taken before the operation. At least 59% of SSI isolates were resistant to the prophylactic antibiotic (Long et al, 2024).

No evidence emerged from all 1610 spinal surgery patients suggesting that the pathogens passed between patients. In other words, the bacteria responsible for the SSI and any genes responsible for antibiotic resistance were probably on the patient's skin before the surgeon made the first incision and infected the wound in the same person (Long et al, 2024).

Remain alert for SSIs

Community nurses should remain alert for SSIs, which can be superficial (skin and subcutaneous tissue), deep (fascia and muscle) or affect abdominal or joint cavities (Guest et al, 2023). Purulent discharge from the incision site or an abscess that involves the surgical bed may indicate SSIs (Seidelman et al, 2023). SSI patients may experience systemic signs of infection (such as fevers and rigors), local erythema, dehiscence, pain, non-purulent discharge or induration (Seidelman et al, 2023).

Preventing SSIs helps reduce antibiotic use and the spread of AMR. Healthcare professionals can help modify several SSI risk factors (Table 1). For example, community nurses can help obese patients lose weight, optimise glucose control in people with diabetes and encourage smoking cessation (Seidelman et al, 2023). Hyperglycaemia, for example, impairs the immune system and promotes protein glycosylation (adding a carbohydrate to the protein). The relatively low blood flow (ischaemia) to adipose tissue reduces delivery of oxygen and antibiotics to the wound. Tobacco causes vasoconstriction, alters collagen metabolism, impairs the inflammatory response and causes ischaemia (Seidelman et al, 2023).

Animals are important reservoirs of resistant bacteria. For example, microbiologists isolated A. baumannii from poultry, wild birds and human lice (Lucidi et al, 2024), while pets can be reservoirs of multidrug-resistant human Escherichia coli strains and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Das et al, 2023; Khairullah et al, 2023). Research, presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases' Global Congress in April, confirms that pet dogs and cats carry the same antibiotic-resistant bacteria as their owners (Menezes et al, 2024).

Researchers tested faecal and urine samples, and skin swabs from dogs, cats and their owners for Enterobacterales, such as E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The prospective study involved five cats, 38 dogs and 78 humans from 43 households in Portugal, as well as 22 dogs and 56 humans from 22 UK households. The pets had skin, soft tissue or urinary tract infections. The owners, on the other hand, were healthy (Menezes et al, 2024).

In Portugal, one dog was colonised by a multidrug-resistant E. coli that produces OXA-181, an enzyme that confers resistance to carbapenems. A total of three cats, 21 dogs and 28 owners harboured Enterobacterales producing extendedspectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) and ampC beta-lactamases. These enzymes increase resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, which treat, for instance, meningitis, pneumonia and sepsis (Menezes et al, 2024).

In one home with a cat and four households with dogs, genetic analysis showed that pets and owners carried the same strains of ESBL/AmpC-producing bacteria. In one of these households, a dog and owner had the same strain of antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae (Menezes et al, 2024).

In another instance, one UK dog was colonised by two strains of E. coli producing NDM-5 beta-lactamase resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems and several other families of antibiotics. About eight dogs and three owners harboured ESBL/AmpC-producing Enterobacterales. In two households, dog and owner carried the same ESBL/AmpC-producing bacteria (Menezes et al, 2024).

Bacteria can pass between pets and humans when owners handle faeces as well as during petting, touching or kissing. So, the researchers suggest, owners should practise good hygiene, including washing their hands following petting and after handling animal waste. In addition, they suggest isolating unwell pets in one room and cleaning other rooms thoroughly (Menezes et al, 2024).

Nevertheless, the diversity of risk factors means that tackling SSI and AMR requires multifaceted interventions (Table 1). For example, a care bundle encompassing preoperative personal patient preparation, preoperative prophylactic antibiotics and strict skin preparation markedly reduced SSI frequency following caesarean section during a 14-month follow up (Corbett et al, 2021).

As part of the bundle, healthcare professionals advised patients to shower or bathe in the 24 hours before surgery and to not remove hairs (eg by waxing or shaving) in the 5 days before surgery (Corbett et al, 2021). Shaving leads to microscopic cuts, which bacteria can use as foci to multiply (Seidelman et al, 2023). Overall, the care bundle reduced SSI rates from 6.7% to 3.5%. The rates of SSI declined from 9.1% to 4.1% in those undergoing emergency caesareans and from 4.4% to 2.7% after elective sections (Corbett et al, 2021).

Modern healthcare depends on effective antibiotics, not just to treat infections but also to facilitate transplants, cancer chemotherapy and surgery (Zampaloni et al, 2024). By optimising SSI care nurses can not only improve wound healing but also help preserve antibiotic efficacy.