Community nursing teams face a range of serious occupational hazards (Chalupka et al, 2008). Working in the community poses additional risks of inoculation injuries because of limited space, poor lighting, lack of hygiene facilities and environmental challenges such as the presence of pets and children. These unpredictable conditions can render staff susceptible to inoculation injuries.

An inoculation injury can be a percutaneous wound caused by a sharp object, such as a needlestick injury (NSI), or a mucocutaneous injury resulting from exposure to body fluids through a bite, scratch or splash. Such injuries can happen during various stages of patient care, including administering injections, incorrectly disposing of sharp objects or handling contaminated waste (Royal College of Nursing, 2023).

The NHS is experiencing mounting pressure, with a growing number of patients receiving care outside of hospital settings. Community healthcare workers bear the greatest burden, caring for patients with complex and chronic illnesses, supporting post-hospitalisation recovery and providing palliative care (Department of Health and Social Care, 2024). This escalating workload can increase the risk of exposure to a bloodborne pathogen, leading to increased worry and stress among healthcare workers (Health and Safety Executive, 2013). While the number of injuries reported each year is high, only a small percentage of those exposed to a bloodborne pathogen are known to have developed serious illnesses as a result (Cheetham et al, 2021).

The consequences of exposure to a bloodborne pathogen depend on several factors, including the individual's age, pre-existing medical conditions such as diabetes, the strength of their immune system and the treatment they receive (Beltrami et al, 2000).

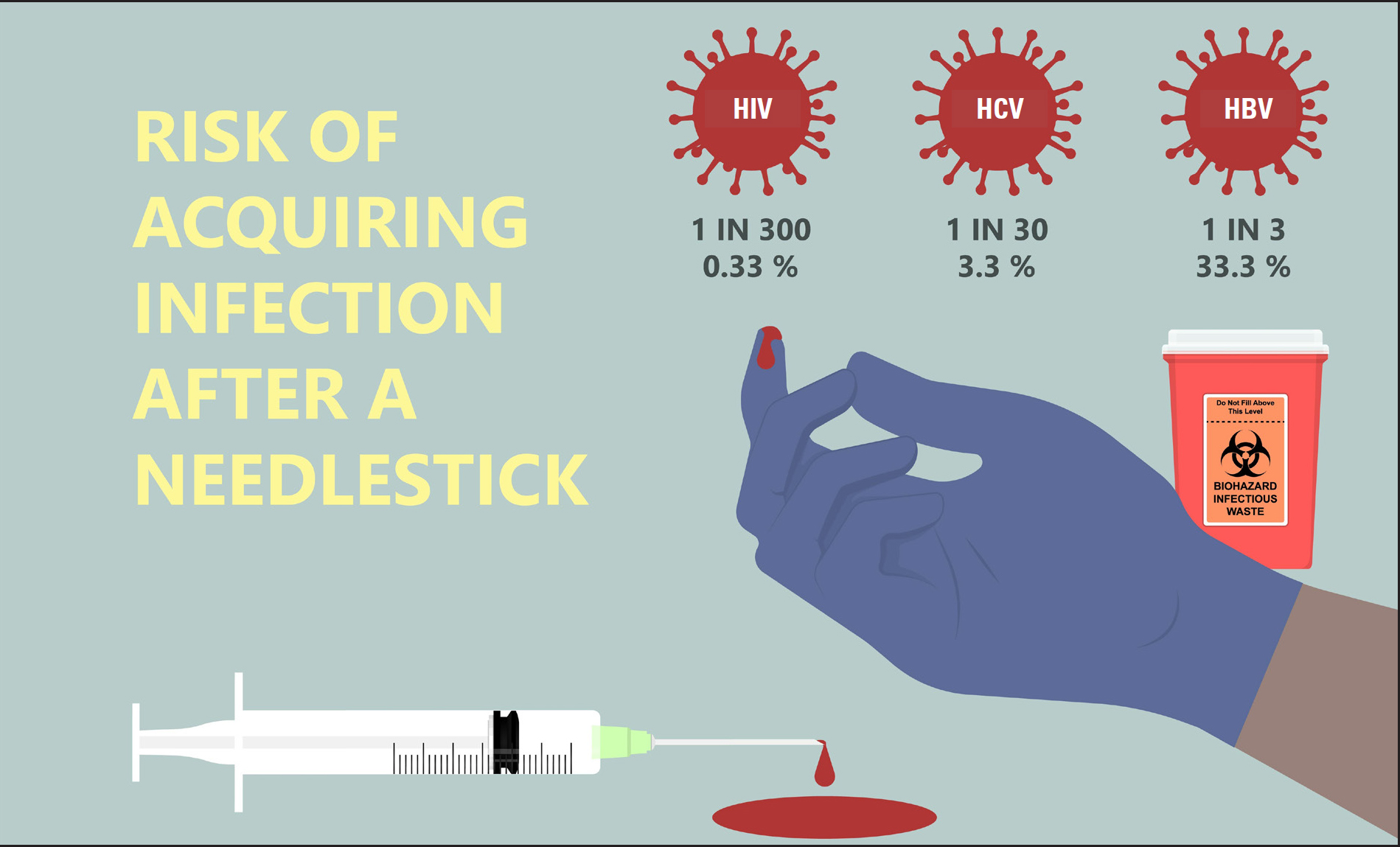

The NHS Resolution (2023) data from 2012 to 2022 reveals a concerning trend in NSIs, with thousands of incidents reported annually. In 2021, the NHS recorded approximately 1200 NSIs, which contribute to significant costs incurred by the healthcare system. The financial burden associated with these injuries includes direct costs such as treatment and testing, estimated at over £100million per year, alongside indirect costs related to staff absenteeism and reduced workforce productivity (NHS Resolution, 2023). Preventing bloodborne pathogen transmission is a crucial aspect of healthcare infection prevention and control. Bloodborne pathogens include viruses such as hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that can be transmitted through contact with contaminated blood or body fluids (Figure 1)(Rai et al, 2021).

HBV is the most common bloodborne pathogen transmitted to healthcare workers typically through NSIs or other percutaneous incidents. The risk of transmission following needlestick exposure can range from 6.0% to 30.0%, depending on factors such as the patient's viral load and the healthcare worker's immune status (whether they are vaccinated or not). If a healthcare worker is vaccinated against HBV, the risk of transmission following exposure is significantly reduced, often approaching zero.

The risk of HCV transmission following a needlestick injury is lower than that of HBV but still significant—estimated at 1.8% from an infected source (Kuhar et al, 2019). While HCV can be effectively treated with antiviral therapy, chronic infection can lead to severe liver disease, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. The risk of HIV transmission from an NSI is approximately 0.3% (1 in 300) when exposed to infected blood. The transmission risk may be higher if the source patient has a high viral load (eg during an acute infection or late-stage HIV). The use of post-exposure prophylaxis, a course of antiretroviral medications, within 72 hours of exposure can significantly reduce the risk of HIV transmission. Early initiation of antiretroviral treatment is crucial for effective prevention (Cresswell et al, 2022).

In the event of an NSI, the exposed individual is attended to by occupational health, the local accident and emergency department or a GP walk-in centre. The protocols for managing an NSI usually involve minimising the risk of infection (especially for initiating time-sensitive treatments such as HIV post-exposure prophylaxis and ensuring appropriate care and follow up (Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2020).

When treating an NSI, the attending healthcare worker will record the details of the incident, including the time and location of the injury, the type of needle and its prior use (eg on a patient or for medication preparation) and the condition of the source patient, if known (eg any known bloodborne infections such as HBV, HCV or HIV). The injury site will be inspected, cleaned and dressed. The person who sustained the NSI will also give a blood sample to establish baseline health and check for immunity to certain diseases including HBC (Chalupka et al, 2008). Subject to feasibility and consent, the source patient may undergo testing for bloodborne infections.

Post-exposure prophylaxis may be considered, particularly if the source is at a high risk for HIV. It should ideally be initiated within 1-2 hours of exposure. If the nurse is unvaccinated or has incomplete immunity, an HBV immunoglobulin injection and/or vaccine booster may be administered. When HCV is suspected, prophylaxis is not needed and regular monitoring for early treatment is initiated. The incident is documented and the nurse is advised to inform their occupational health department or the employer.

A report may be submitted through workplace reporting systems, such as the Reporting of Incidents, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (generally known as RIDDOR) in the UK. Scheduled follow ups with occupational health (at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months) are arranged to monitor blood tests for seroconversion to infections such as HIV or HCV, as well as to provide psychological support and counselling, given the distressing nature of NSIs (Chalupka et al, 2008).

Preventing the transmission of bloodborne pathogens is a critical component of healthcare infection prevention and control practices (Schuurmans et al, 2018). All community nurses must follow these practices to minimise the risk of infection transmission and prevent the spread of bloodborne pathogens (UK Health Security Agency, 2024).

Use of personal protective equipment

Community nurses must always wear gloves when handling blood or body fluids to avoid direct contact with potentially infectious material. They should wash hands before and after patient contact, before putting on and after removing gloves, and change gloves between patients. Nurses are advised to cover existing wounds, skin lesions and any breaks in exposed skin with waterproof dressings and to wear gloves if their hands are extensively affected.

Gloves should be worn when cleaning equipment prior to sterilisation or disinfection, handling chemical disinfectants and cleaning up spillages to protect against bloodborne pathogens. The use of masks, face shields and goggles is essential when there is a risk of blood splashes or spray reaching susceptible mucous membranes of the face (Jin et al, 2020). Gowns and aprons should be worn to protect clothing and skin when there is a risk of significant fluid exposure.

Sharps safety and safe needle practices

Standard precautions

Hygiene

Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water or use alcohol-based hand sanitiser before and after patient contact, especially after handling sharps or body fluids (Brockhaus et al, 2024)

Contaminated materials

Safely handle and dispose of any contaminated clothing, linens or medical equipment to avoid transmission of bloodborne pathogens.

Barriers

Use appropriate barriers (eg dressings, gloves) to prevent bloodborne pathogens from entering the body through broken skin or mucous membranes (World Health Organization, 2022).

Education and Training

Community nurses must receive regular training on infection prevention and control practices, including the proper use of personal protective equipment, safe handling of sharps and proper disposal of hazardous materials (Cutter and Gammon, 2007). Research has shown a reduction in the rate of sharps following education and training, and concluded that ongoing, focused and continuous education is essential in preventing sharps injuries (Cheetham et al, 2021). Audits of sharps usage and handling must be conducted at least annually. The findings of these audits should be communicated to staff, prompting any necessary improvements in practice.

Vaccination and Prophylaxis

Community nurses should be vaccinated against HBV to protect against potential exposure (UK Health Security Agency, 2024). For potential exposure to HIV, immediate access to antiretroviral therapy can significantly reduce the probability of transmission. Similarly, post-exposure prophylaxis for HBV may be recommended for exposed individuals (Cresswell et al, 2022).

Infection prevention and control policies and procedures

Comprehensive protocols must be put in place to prevent bloodborne pathogen transmission in community practice, including the implementation of the 10 key standard infection control precautions (SICPs), which address practices that prevent NSIs and promote a safe working environment (NHS England, 2022a). A sharps management policy and guidelines for handling inoculation injuries must also be readily available.

Community nurses should be provided with surface wipes for cleaning and disinfecting surfaces and any equipment that may be contaminated with blood or body fluids (Payne and Peach, 2021). Infection prevention and control guidance emphasises the prompt removal of blood spills, disinfection of surfaces and adherence to safe procedures for disposing of contaminated waste. Preventing exposure to bloodborne pathogens is outlined in the safe disposal of clinical waste guidelines (NHS England, 2022b).

Post-exposure management

Post-exposure management is crucial because it helps mitigate potential risks associated with exposure to harmful substances or pathogens. It typically involves taking immediate action, such as cleaning the affected area or administering post-exposure prophylaxis, followed by regular testing and counselling to monitor health outcomes, address concerns and provide necessary support.

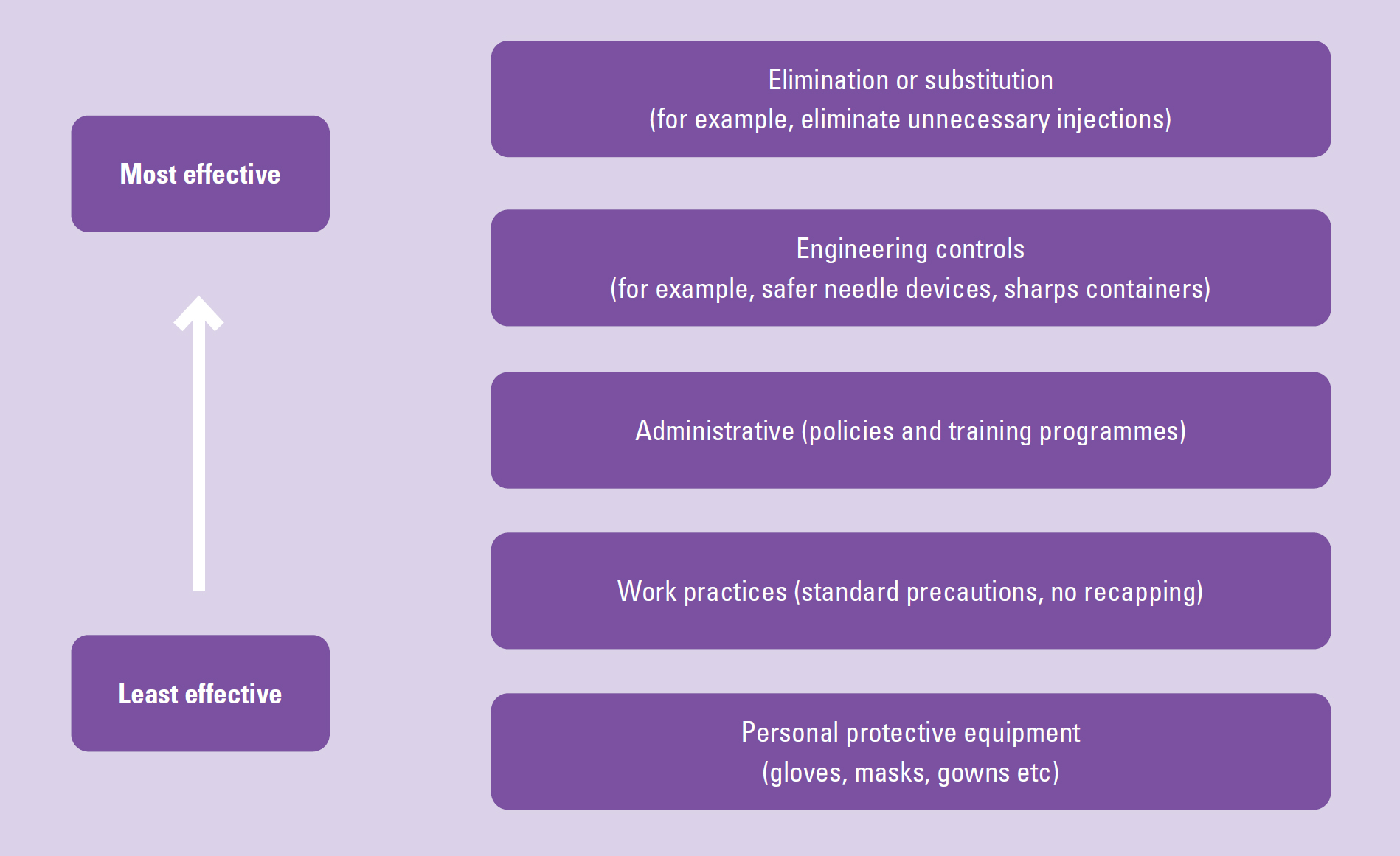

In the UK, the main focus has been on changing individual behaviours of sharps users and effective follow up and support after an injury, rather than prevention. Measures to prevent sharps injuries can best be implemented using the hierarchy of controls and principles of prevention frameworks (Figure 2)(Royal College of Nursing, 2023).

The hierarchy of controls is a framework used to prioritise and implement control measures to reduce or eliminate workplace hazards, including sharps injuries in healthcare settings. The hierarchy is typically structured from the most effective to the least effective control measure. These principles emphasise avoiding the risk (eliminate sharps where possible), evaluating the risks that cannot be avoided (using engineering controls like safety needles) and combines preventive measures (adopting safe practices such as using sharps containers and incorporating administrative controls by implementing policies and training staff). While the framework specifies the wearing of personal protection equipment to create a barrier between the worker and the potential hazard, it also notes that this will only offer limited protection and cannot prevent NSIs (Royal College of Nursing, 2023).

Conclusions

As of June 2024, more than 1million people had been waiting for community services. Healthcare workers providing care in the community are under constant pressure. Therefore, it is important to adopt measures to reduce sharps injury and ensure that these are embedded firmly into practice. Preventing bloodborne pathogen transmission requires a multifaceted approach, as discussed earlier in the article, along with the implementation of 10 key SICPs and the hierarchy of controls to further guide the prevention strategy. The aim is to create a safer work environment, reduce exposure to bloodborne pathogens and improve after care.