No matter how dedicated someone is to their skincare regimen, no matter how much a person spends, it is impossible to turn back time. After all, skin ageing consists of two elements: chronological and extrinsic. Chronological (intrinsic) ageing manifests as stiff, dry, thin skin and fine wrinkles (Franco et al, 2022; Wahhab et al, 2024). Extrinsic factors exacerbate intrinsic ageing. Sun-exposure (photo-ageing) produces deep wrinkles, uneven pigmentation and telangiectasias (spider veins) as well as increasing the risk of several skin cancers (Wahhab et al, 2024). Other extrinsic factors that influence skin ageing include smoking, pollution, poor diet, cosmetics, sleep disturbance, stress and temperature (Franco et al 2022; Wahhab et al 2024).

Age-related changes to the skin influence the likelihood of developing certain diseases. For instance, while atopic dermatitis is an archetypal childhood disease, the prevalence of atopic dermatitis peaks twice: in childhood and at older age (de Lusignan et al, 2021). Other common dermatological diseases in older people include fungal infections, xerosis (dry skin), statis and irritant contact dermatitis, and drug adverse events (Sanders et al, 2024). In addition, dermatological ageing can be more than skin deep. Atopic dermatitis seems increase the likelihood of developing Alzheimer's disease (Woo et al, 2023). Sometimes, skin ageing imposes a psychological burden that is ‘often overlooked or frankly ignored’ (Russell-Goldman and Murphy 2020). This feature introduces the relationship between skin ageing and dermatological diseases in older people.

Under the surface

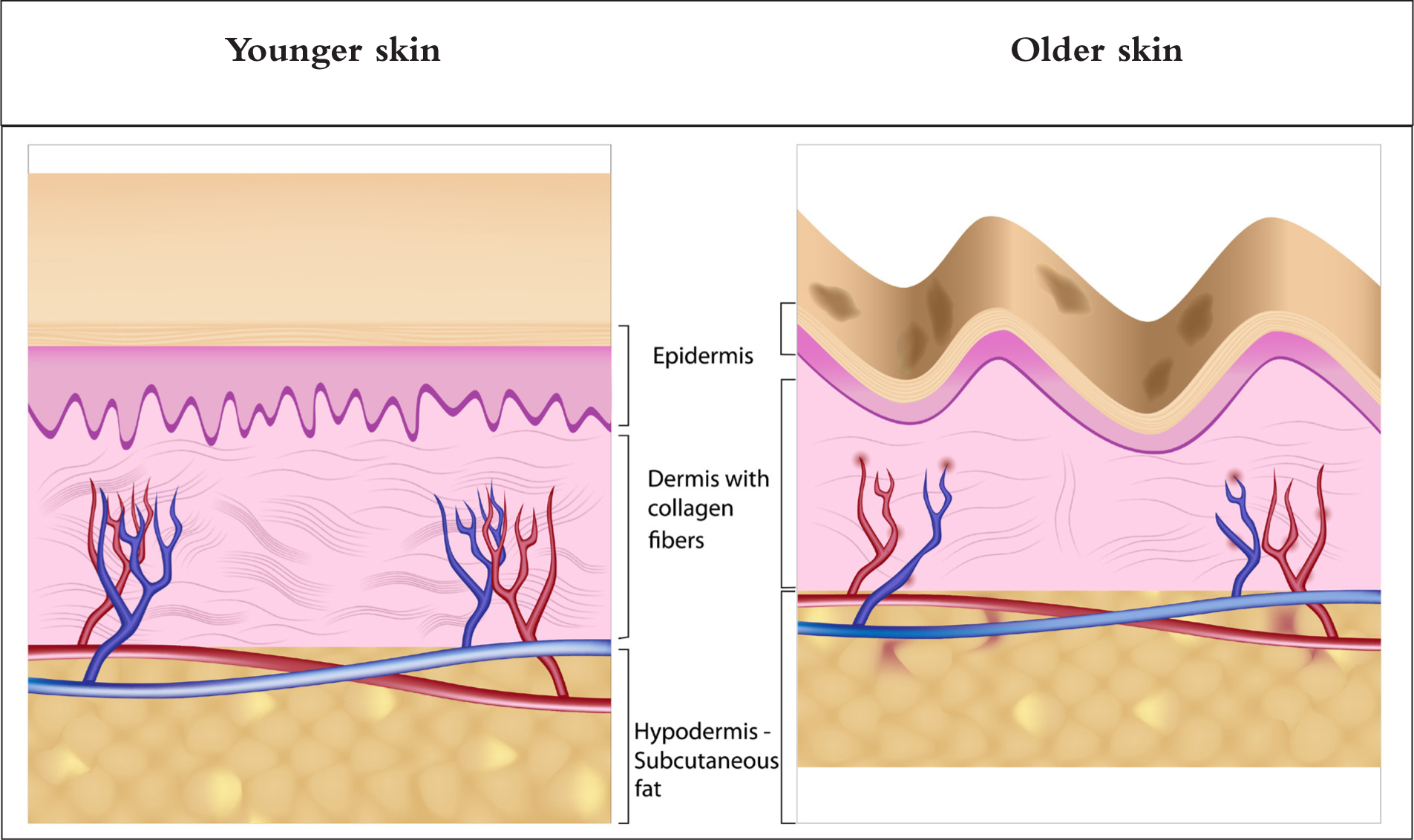

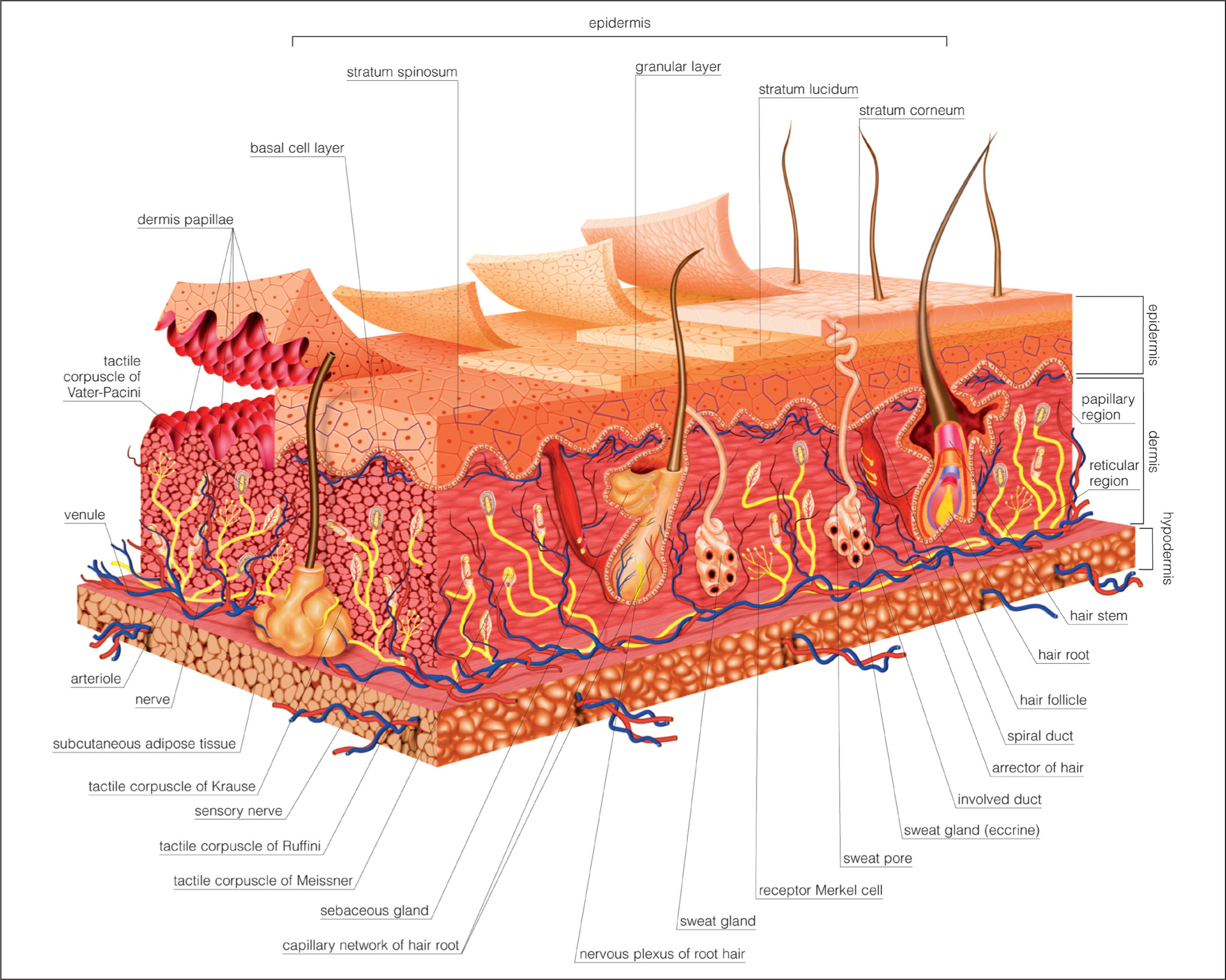

Ageing is associated with numerous physical, immunological and molecular changes that fundamentally alter skin structure and function (Figure 1). There are too many factors, which are understood in too much detail, to summarise here. The following examples offer an essence of the evidence.

The thickness of the epidermis declines by 10–50% between 30 and 80 years of age (Wahhab et al, 2024). Meanwhile, fat (adipose tissue) distribution alters. The amount of subcutaneous adipose tissue declines, which contributes to the emergence of wrinkles (Salminen et al, 2022; Wahhab et al, 2024). The amount of visceral adipose tissue (around organs) and fat in muscle increase with age (Wahhab et al, 2024). The erosion of rete ridges and dermal papillae, projections from the epidermis into the dermis, is one of the first age-related skin changes (Figure 2). The papillae contain capillary loops that are partly responsible for nourishing the epidermis. These changes undermine the skin's resistance to shearing forces. This is why removing a wound plaster without damaging skin is more difficult in elderly people than in children (Russell-Goldman and Murphy, 2020).

The amount of collagen (a protein that gives skin structure and strength) in the skin declines and becomes fragmented and coarser as people get older. For example, the amount of collagen in the sun-protected dermis of people older than 80 years of age is 75% lower than in younger people (Russell-Goldman and Murphy, 2020).

Meanwhile, elastin fibres (which, as the name suggests, helps maintain elasticity) in the skin degrade and the amount of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the dermis declines (Salminen et al, 2022). The ECM is a network of collagen, elastin and other components that creates a scaffold supporting tissues. The ECM also provides physical, biochemical and mechanical signals that regulate tissue function (Iwasa and Marshall, 2016). Meanwhile, oxidative stress from free-radicals seems to contribute to intrinsic and extrinsic ageing (Salminen et al, 2022). Together these changes undermine the skin's barrier function. This is why older people are prone to xerosis and, as discussed later in the article, atopic dermatitis and skin infections (Sanders et al 2024).

Incidentally, older skin contains fewer peripheral nerve endings than younger skin. Consequently, people who are 70 years and older show a marked decline in their ability to sense vibration and discriminative touch, most notably in their hands and feet (Wahhab et al, 2024).

Skin as an immune organ

The skin is far more than a simple physical barrier. Skin is also a dynamic immune organ, rich in white blood cells and other components of the immune system. Keratinocytes (the most common cell in the epidermis) and melanocytes (responsible for skin pigmentation) also show distinctive immune properties (Salminen et al, 2022). Chronological ageing and ultraviolet radiation produce chronic low-grade inflammation in the skin (so-called inflammaging). This triggers a complementary immunosuppression, which promotes ageing and increases the risk of several age-related diseases (Salminen et al, 2022). Older adults typically show immunosenescence: a progressive age-related weakening of the immune response that can predispose people to, for instance, infections and cancer (Wahhab et al, 2024).

Immunosenescence and decreased cell proliferation lengthens wound healing time in people aged older than 65 years (Wahhab et al, 2024). Skin stem cells, which reside in the rete ridges, differentiate into several mature cell types to replace old and damaged cells (Iwasa and Marshall, 2016; Russell-Goldman and Murphy, 2020). With age, stem cells become less active, which reduces the skin's capacity to repair damage (Franco et al, 2022; Wahhab et al, 2024). As a result, the time for the stratum corneum to renew increases by 50% in older adults compared to those aged younger than 50 years (Wahhab et al, 2024).

Meanwhile, genetic changes (such as mutations) accumulate, especially in sun-exposed areas (Wahhab et al, 2024). Cells divide by moving through a series of defined, tightly controlled steps, together known as the cell cycle. The cell cycle has several checkpoints that recognise DNA damage (which could lead to cancer) and other abnormalities. These checkpoints can trigger controlled cell death (apoptosis) or induce the cell to permanently exit the cell cycle, also known as senescence (Iwasa and Marshall, 2016).

With age, the number of senescent cells in the skin increases, which is a mixed blessing (Franco, et al 2022; Wahhab et al, 2024). Senescent cells promote wound healing and reduce cancer risk (Franco et al, 2022; Wahhab et al, 2024). But the accumulation of senescent cells can cause dermatological dysfunction. Some senescent cells are proinflammatory (Salminen et al, 2022).

Xerosis

Between 38% and 58% of older people experience xerosis (Sanders et al, 2024). Usually xerosis in older people results from age-related changes in stratum corneum structure and the epidermis's lipid (fat) content. While xerosis in elderly adults typically affects the lower legs, many include the hands or trunk. Pruritus may lead to scratching or rubbing, increasing the risk of skin infections (Sanders et al, 2024).

In addition, several medications and concurrent diseases increase the risk of xerosis in elderly people including radiation, end-stage renal disease, thyroid disease, HIV and cancers (Sanders et al, 2024). Indeed, elderly people are more likely to develop eczema-like reactions while taking calcium channel blockers and, possibly, other antihypertensives than younger people. Future research needs to determine the cause of the reaction, such as the contribution made by polypharmacy and changes in drug metabolism with age (Sanders et al, 2024). In the meantime, a recent review suggests maintaining ‘a high index of suspicion for adverse drug reactions when managing dermatoses in older patients’ (Sanders et al, 2024).

Fungal skin infections

Between 14% and 64% of people aged older than 65 years develop fungal skin infections, such as tinea pedis (athlete's foot) or tinea corporis (ringworm on the body) (Sanders et al, 2024). A review of 108 studies reported a 4% global prevalence of toenail onychomycosis (fungal nail infection) caused by dermatophytes (ringworm) (Gupta et al, 2024). Accurate diagnosis is important; antibiotics and steroids can mask or exacerbate the symptoms of a dermatophyte infection, while delayed or ineffective treatment can facilitate transmission and encourage resistance (Chanyachailert et al 2023, Dellière et al 2024). A typical ringworm rash is red or silver and may appear darker than the surrounding skin. So, the rash may be harder to see on brown and black skin as compared to white skin (NHS, 2024).

The presentation depends on the fungus. Dermatophytes with a preference for humans (anthropophilic) usually cause desquamation (shedding or peeling of the outer layers of the skin), itch and low-level inflammation (Chanyachailert et al, 2023; Dellière et al, 2024). Zoophilic (prefer animals) and geophilic species (grow in soil) tend to cause more severe inflammatory reactions in humans than anthropophilic fungi because they are not as well-evolved for life on human skin. (Chanyachailert et al, 2023; Dellière et al, 2024). Migration of the fungi from tinea pedis into the nail, decreased vascular perfusion and immunosenescence may increase the risk of onychomycosis in older people (Sanders et al, 2024). Recurrent fungal diseases may also suggest a comorbidity such as diabetes, malnutrition or vitamin deficiencies (Sanders et al, 2024). Dermatophyte infections are usually superficial. Immunosuppressed people can, however, develop deep dermatophyte infections, which are often misdiagnosed (Dellière et al, 2024).

Mobility issues contribute to the relatively high rates of fungal infections among older people. For example, patients who are unable to bathe daily or have mobility limitations are especially prone to developing tinea corporis (Sanders et al, 2024). Knee osteoarthritis increased the risk of toenail onychomycosis caused by dermatophytes 14.6 times, probably because mobility issues hinder hygiene and patients' ability to apply topical treatments (Gupta et al, 2024).

Eczema and Alzheimer's

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis peaks twice: in childhood and older age (Woo et al, 2023). A UK study found that 2.8% of adults aged 30–39 years had atopic dermatitis, down from a peak of 16.5% in 2-year-olds. The prevalence rose to 4.9%, 6.8% and 9.9% in people aged 60–69 years, 70–79 years and 80 years and older, respectively (de Lusignan et al, 2021). Atopic dermatitis in older people is often more active and severe than in other age groups (Sanders et al, 2024). Elderly patients with atopic dermatitis show lesions on their face and flexor surfaces less often as well as having lower levels of serum immunoglobin E (IgE; the ‘allergy antibody’) and eosinophils (a type of white blood cell), as compared to younger people and children (Sanders et al, 2024). The skin microbiome changes with age, which may leave older people especially susceptible to infection (Wahhab et al, 2024). People with atopic dermatitis are 20 times more likely to be colonised with Staphylococcus aureus than healthy controls (Thyssen et al, 2023). Atopic dermatitis patients are also 1.3 to 2.0 times more likely to develop ear infections, strep throat and urinary tract infections than controls (Thyssen et al, 2023).

Atopic dermatitis is associated with numerous other comorbidities, many of which become more pronounced with age, such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and Alzheimer's disease (Thyssen et al, 2023; Woo et al, 2023). A Korean study compared 38 391 people aged 40 years and older with atopic dermatitis with 2 643 602 controls. Atopic dermatitis was associated with a 7.2% increased risk of any kind of dementia and a 5.1% increased risk of Alzheimer's disease. The association was especially marked in people younger than 65 years of age: increases of 20.7% and 21.0% for any dementia and Alzheimer's disease, respectively (Woo et al, 2023).

The mechanisms linking atopic dermatitis and Alzheimer's disease need further investigation. However, pro-inflammatory messengers (cytokines and chemokines) can cross the blood-brain barrier and contribute to neurodegeneration (Woo et al, 2023). Furthermore, systemic inflammation may weaken the blood brain barrier, which probably hastens the progression of Alzheimer's disease (Sanders et al, 2024).

Irritant contact dermatitis, especially in the groin and buttocks, is also common among older adults. Incontinence-associated dermatitis occurs in 3.4% of older people with incontinence and up to 23% of adults in long-term care facilities (Sanders et al, 2024). A US study suggests that about 6% of people older than 50 years live with stasis dermatitis (Lebwohl et al, 2023). Poor circulation in the lower legs leads to blood pooling, which causes erythema, pruritus and thick scales on the lower legs. Statis dermatitis also undermines the skin's barrier function, predisposing to allergic contact dermatitis from compression bandages and over-the-counter and prescription medicines (Sanders et al, 2024).

Skin ageing is inevitable. Chronological and extrinsic ageing partly, but not solely, account for the increased risk of numerous age-related dermatological diseases. By considering the biological basis of skin ageing, nurses can better manage the A–Z of age-related dermatological diseases from atopic dermatitis to zoophilic fungal infections.