Demographic shifts and hospital reorganisations mean that patients are discharged to their homes at a much faster rate and with more comprehensive healthcare needs than previously (Salmond and Echevarria, 2017; Ylitörmänen et al, 2019). This trend is especially pronounced among older patients for whom the transition from hospital to homecare is marked by an even higher level of complexity than in other patient groups (Norlyk et al, 2020; Moore et al, 2021). Consequently, homecare services face a growing demand to address these comprehensive care needs of the older population, ensure seamless treatment trajectories and deliver quality healthcare (Hansson et al, 2018; Norlyk et al, 2020; Dolu et al, 2021).

Collaboration and communication between healthcare staff are key factors influencing the quality and safety of patient care during the transition from hospital to homecare (Hansson et al, 2018; Dolu et al, 2021; Manias et al, 2021). Collaboration is a process that involves sharing knowledge and ensuring common objectives between two or more parties. It necessitates an awareness of expedient interactional attitudes and a thorough understanding of work roles and task distribution (Lemetti et al, 2015). Within nursing, intraprofessional collaboration includes negotiation in non-hierarchical relationships, and establishing and maintaining a shared understanding among involved nurses grounded in their professional knowledge and competencies (Ylitörmänen et al, 2019). Accordingly, intraprofessional collaboration is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon comprising relational and communicational processes. In relation to transitional care from hospital to home, intraprofessional collaboration may be even more complex as it includes cross-sectoral collaboration in which hospital nurses (HNs) and community nurses (CNs) need to exchange vital knowledge and information concerning care for older patients with complex care needs.

Existing knowledge on intraprofessional collaboration between HNs and CNs during the discharge process of older patients indicates that collaboration may be challenged by a range of social and professional factors. These include unclear roles and diverse skills and knowledge bases (Moore et al, 2019), and also by difficulties in reaching mutual agreements about goals, practices and responsibilities (Lemetti et al, 2021). Collaboration between nurses in transitional care is of great concern as research has reported that failure to communicate and collaborate during the discharge process may seriously disrupt continuity of care for older patients. Studies have shown that between 5% and 79% of readmissions may be avoided when information shared between HNs and CNs is accurate (van Walraven et al, 2011). Poor communication and incomplete sharing of information can also harm the patient, limit patient safety and increase the risk of poor medical outcomes (Laugaland et al, 2012). Furthermore, older patients discharged from hospital have experienced that readmissions were inevitable because of inadequate professional competencies in the homecare setting (Elkjær et al, 2023), making them feel insecure about their post-discharge care resulting from lack of continuity in the transition phase (Nielsen et al, 2019; Kalánková et al, 2021).

A scoping review focusing on the collaboration between HNs and CNs during the transition of older patients highlighted that conflicts in the nurses' collaborative endeavours were influenced by varying perceptions of their positions within the nursing hierarchy (Moore et al, 2021). The authors stressed that future research should examine collaborative practices among HNs and CNs more deeply to understand practices that may foster conflicts between nurses (Moore et al, 2021). The present study aimed to gain deeper understanding of collaborative practices that have the potential to fuel tension in the collaboration between HNs and CNs during discharge of older patients from hospital to homecare.

Method

The present study adopted a meta-ethnographic approach including a framework of seven interwoven phases (Noblit and Hare, 1988). This approach was chosen because of its interpretive perspective and ability to generate a profound understanding of previous research findings within a specific research interest.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted during March and April 2022 using the PubMed, CINAHL, Embase and Scopus databases, supported by a research librarian. The Mesh terms and keywords combined were, ‘hospital to home transition’, ‘aged’, ‘transitional care’, ‘collaboration’, ‘cooperation’ and ‘qualitative research’ using the Boolean operators OR and AND. The systematic search was supplemented by hand-searching relevant journals and reference lists to minimise the risk of missing any relevant studies.

The inclusion criteria were studies in English, Danish, Norwegian or Swedish, age group (65 years or more) and works published within the past 10 years (2012 to 2022).

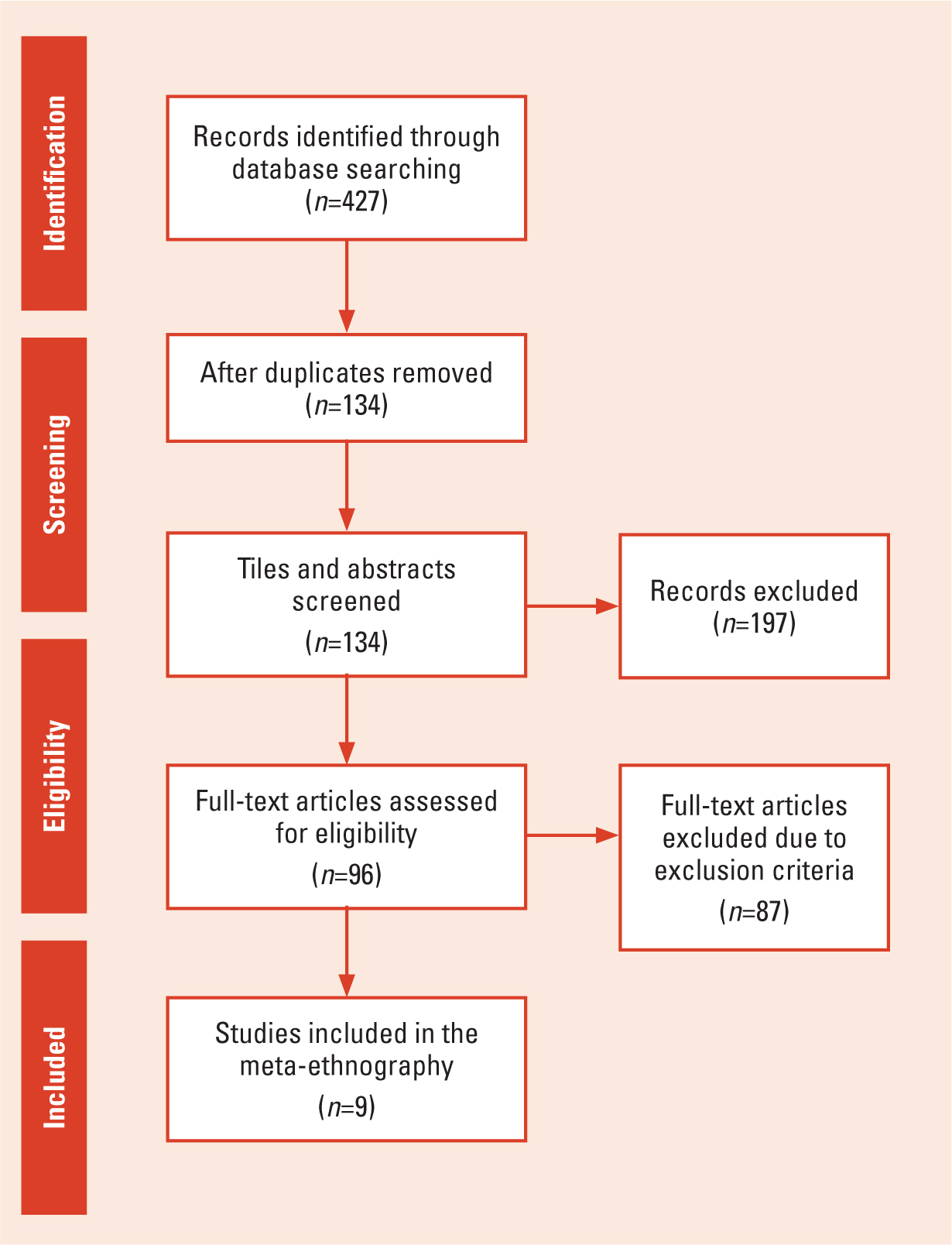

As presented in Table 1, a total of 427 articles met the initial search criteria. Supplementary searches failed to provide any additional articles. Following the removal of 134 duplicates, the 293 articles remaining were screened for relevance based on their titles and abstracts, and 96 were selected for full reading. All studies included were required to carry sufficient information and detailed descriptions essential for establishing a proper interpretation that would contribute to generating new knowledge in the realm of research interest (Noblit and Hare, 1988). In this study, the research interest was reported collaborative practices and aspects potentially fostering or aggravating tensions in the collaboration between HNs and CNs. Accordingly, studies reporting on the experiences of HNs and CNs and their collaborative practices related to older patients' discharge processes were considered for selection and analysis. Also included were articles covering transition from hospital to home as experienced by health professionals if the included participants were mainly HNs and CNs and it was possible to extract their experiences. Articles were excluded if they reported issues relating to transitional care from the perspectives of patients, relatives or other health professionals than nurses (occupational therapists or general practitioners). Discussion papers and review papers were also excluded. Studies concerning other patient age groups outside of 65 years or more were also excluded. From reading the 96 articles, nine relevant articles that aligned with the aim of this study were identified and were analysed. These articles were evaluated using the Clinical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool and all met the criteria. Figure 1 displays a PRISMA flow diagram of the screening process. Table 2 presents the included articles.

| Database | Search outcome (filters: Language: Danish, English, Norwegian, Swedish; Age: 65+; Study range: 2012–2022) | Included studies after removing duplicates |

|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | 276 | 66 |

| Embase | 9 | 6 |

| CINAHL | 97 | 14 |

| Scopus | 45 | 10 |

| Total | 427 | 96 |

| Authors | Country | Title | Study design | Purpose/aim of study | Participants/context | Data collection methods and data analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olsen et al (2013) | Norway | Barriers to information exchange during older patients' transfer: nurses' experiences | A qualitative descriptive exploratory study design | To describe nurses' experiences of barriers that influence their information exchange during the transfer of older patients between hospital and home care | A total of 14 registered nurses, 2 men and 12 women, with a median age of 36 years. Hospital setting in central Norway and a Health Care agency affiliated with this hospital | Focus group interviews. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis |

| Kirsebom et al (2013) | Sweden | Communication and coordination during transition of older persons between nursing homes and hospital still in need of improvement | A qualitative descriptive study design | To investigate registered hospital and nursing home nurses' experiences of coordination and communication within and between care settings when older persons are transferred from nursing homes to hospital and vice versa | A total of 14 hospitals and 6 nursing home registered nurses, all but one of whom were female. |

Focus group discussions. Data were analysed using content analysis |

| Petersen et al (2019) | Denmark | It is two worlds: cross-sectoral nurse collaboration related to care transitions: a qualitative study | A descriptive qualitative study design | To explore how hospital and home care nurses talk about and experience cross-sectoral collaboration related to the transitional care of frail older patients | A total of 79 nurses from three medical and surgical hospital wards and eight different units in 6 municipalities. |

Focus group interviews. Data were analysed using thematic analysis |

| Melby et al (2015) | Norway | Patients in transition – improving hospital-home care collaboration through electronic messaging: providers' perspectives | A descriptive qualitative interview study design | To explore how the use of electronic messages supports hospital and community care nurses' collaboration and communication concerning patients' admittance to and discharges from hospitals | A total of 41 hospital and homecare nurses. |

In-depth interviews. Data were analysed with a combined approach comprising both a deductive organising framework and an inductive approach |

| Lemetti et al (2017) | Finland | An enquiry into nurse-to-nurse collaboration within the older people care chain as part of the integrated care: a qualitative study | A qualitative study design informed by grounded theory | To describe nurses' perceptions of their collaboration when working between hospital and primary healthcare within the older people care chain | In all 28 registered nurses, 14 from hospitals and 14 from primary healthcare. |

Focus group interviews. Data were analysed using dimensional analysis |

| Jones et al (2017) | USA | Connecting the dots: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients | A descriptive qualitative study design | To describe home health care (HHC) nurse perspectives about challenges and solutions to coordinating care for recently discharged patients | A total of 56 HHC nurses recruited from 6 homecare agencies. |

Focus group interviews. Data were analysed using thematic analysis |

| Lundereng et al (2020) | Norway | Nurses' experiences and perspectives on collaborative discharge planning when patients receiving palliative care for cancer are discharged home from hospitals | A qualitative study with a descriptive and explorative design | To explore nurses' experiences and perspectives on discharge collaboration when patients receiving palliative care for cancer are discharged home from hospitals | 10 nurses, 5 from oncology wards at a university hospital and 5 from home care services in 4 municipalities within the hospital's catchment area. |

Individual semi-structured interviews. Data were analysed using systematic text condensation |

| Foged et al (2018) | Denmark | Nurses' perspectives on how an e-message system supports cross-sectoral communication in relation to medication administration: a qualitative study | A qualitative design | To describe nurses' perspectives on how an e-message system supports communication between hospital and homecare nurses in relation to medication administration | A total of 79 nurses from 8 hospital wards and 6 municipalities. |

Focus group interviews and participant observations. Data were analysed using content analysis |

| Petersen et al (2018) | Denmark | Nurses' perceptions of how an e-message system influences cross-sectoral communication: a qualitative study | A qualitative design with an anthropological approach | To investigate hospital and home care nurses' experiences on how an e-message system influences cross-sectoral communication two years after being introduced. | A total of 79 nurses from 8 medical and surgical wards in the hospital and 6 municipalities (homecare services) 11 nursing units for participant observations. |

Focus group interview and participation observations. Data were analysed using content analysis |

Data analysis

In the seven phases of meta-ethnography (Noblit and Hare, 1988), researchers identify, justify, interpret and synthesise findings from previous qualitative studies. Their goal is to attain a new comprehensive interpretation of these studies while remaining faithful to the described meaning conveyed in each individual study. The phases cover the process from establishing the research interest to expressing the synthesis.

The phases in meta-ethnography, involving analysis of the data and expression of the synthesis, were performed as follows. First, all nine articles were read and reread with a specific focus on key themes and phrases describing HNs and CNs experiences of collaborative practices with a potential to fuel tension during older people's discharge from hospital to homecare. This was followed by a comparison of the data collected to identify patterns of meaning related to these collaborative practices across the studies. Instances in which issues concerning collaboration were referred to were identified and these instances were extracted. Next was the process of translating the studies into one another by further considering how key themes or phrases across and within each study related to or disconfirmed each other. To reach a new interpretation, the preliminary findings identified in the previous phases were coded and arranged into meaningful units. Initially, 18 preliminary codes were identified, providing an overarching explanation of the collaboration between HNs and CNs. The initial codes were subsequently categorised into the five themes presented below.

Findings

The five themes identified were: ‘a simmering distrust: uncertainty about information needs’, ‘the negative loop: unequal prioritisation leading to inadequate communication’, ‘the invisible wall: communication systems threaten credibility’, ‘tone of voice: misinterpretation of collegial engagement’ and, ‘different care perspectives: engendering a battlefield’. These themes reveal how uncertainty about information needs, distrust towards the information given, information exchanged in terms of prioritisation and adequacy, and the tone used in direct communication all appeared to have the potential to fuel tension in, and thus potentially hinder, intraprofessional collaboration between HNs and CNs.

A simmering distrust: uncertainty about information needs

The potential for tensions to arise in the collaboration between HNs and CNs increased because of a mutual lack of knowledge regarding each others' information needs. This issue was especially distinct when uncertainties dominated crucial information required by CNs to ensure proper patient care after discharge.

Both HNs and CNs expressed a pronounced sense of responsibility for ensuring seamless and secure transitions for older patients while these patients were under their care (Petersen et al, 2019; Lundereng et al, 2020). To honour this responsibility, HNs needed to share all relevant information regarding a patient's condition and treatment with CNs. Nonetheless, uncertainty concerning CNs' specific information needs often dominated among HNs (Olsen et al, 2013; Lundereng et al, 2020). This state of uncertainty concerning information needs held the potential to create deficits in collegial cohesiveness across sectors, as both HNs and CNs perceived the information shared between them to be inadequate. To address this challenge, nurses from both sectors requested greater insights into each others' working conditions and more explicit guidelines regarding exchange of information during the discharge process from hospital to homecare (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Olsen et al, 2013; Petersen et al, 2019).

Furthermore, the uncertainty about the other party's information needs would potentially lead to negative perceptions and assumptions among the nurses regarding the willingness of their counterparts to engage in collaboration (Lundereng et al, 2020). Feelings of frustration and distrust related to these underlying assumptions would impede open and trusting communication, thereby influencing their collaborative efforts. Consequently, the cohesion between CNs and HNs, which was needed during the patient's transition between hospital and homecare, would occasionally be undermined by an inadequate understanding of the information requirements prevailing within the opposing sector. This dynamic had the potential to produce breakdowns in collaboration characterised by distrust between CNs and HNs, causing a lack of engagement in or withdrawal from their intraprofessional collaboration.

The negative loop: unequal prioritisation leading to inadequate communication

Different prioritisation of information exchange tasks among HNs and CNs had the potential to fuel tension within the nurses' intraprofessional collaborative practices. CNs considered information exchange in the discharge process of older patients from hospital to homecare to be the bedrock of caregiving responsibilities. Conversely, HNs reported that information exchange tasks were frequently given lower priority than more acute nursing tasks within the hospital setting, such as treating symptoms of nausea and pain etc. (Olsen et al, 2013; Petersen et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2019; Lundereng et al, 2020). The low prioritisation of information exchange tasks among HNs would lead to delayed discharge planning (Petersen et al, 2018; Lundereng et al, 2020). However, delays, challenged CNs who needed to organise homecare services by ensuring provision of essential medications and required equipment (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Lundereng et al, 2020). CNs expressed a sense of unequal consideration for their needs coupled with a sense that their work was being undervalued and marginalised by HNs (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Lundereng et al, 2020). As a result of these challenges, CNs often needed to highlight the difficulties in planning homecare services because of delayed information, hoping that HNs would prioritise discharge planning better (Lundereng et al, 2020).

Time pressure was one of the factors that challenged HNs' prioritisation of discharge planning for older patients. For example, in some cases, HNs needed to hand over responsibility for communicating patient care and treatment information to colleagues or discharge coordinators because of heavy workloads, staff shortages and scheduling inconsistencies (Olsen et al, 2013; Petersen et al, 2018). This created an intermediate link in the information exchange between CNs and HNs. This intermediate link reinforced CNs' experience that they were not receiving adequate information concerning the older patient's physical condition, medication list, follow-up care plans etc. (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Olsen et al, 2013; Melby et al, 2015). Consequently, deprioritising information exchange among the HNs and delegating it to colleagues risked impeding the information flow between HNs and CNs, creating a ‘negative loop’ that exacerbated underlying tensions in their cross-sectoral collaborative efforts.

The invisible wall: communication systems threaten credibility

Limited opportunities for exchange of information within electronic health report (EHR) systems constituted a potential communication barrier between HNs and CNs that would fuel tension in their intraprofessional collaboration. Communication via the EHR systems primarily relied on predetermined elements with limited free-text input (Melby et al, 2015; Foged et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2018Lundereng et al, 2020) creating an ‘invisible wall’ impeding intraprofessional collaboration, resulting in predominantly one-way communication between HNs and CNs. CNs, in particular, expressed frustration with the inadequacy of communication and information exchange impacting their care tasks in homecare settings. Frequently, CNs found themselves forced to collect fragments of information from various sources to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the discharged older patient's situation. This need arose from either insufficient information reported by HNs or their own lack of access to essential details within the EHR systems (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Jones et al, 2017; Foged et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2018). Consequently, palpable frustration experienced by CNs led them to question the credibility of information conveyed by the HNs, intensifying tension within their intraprofessional collaboration.

Tone of voice: misinterpretation of collegial engagement

Low engagement in verbal communication among HNs, characterised by the use of an unfriendly tone when direct contact was initiated by CNs, would potentially trigger frustration and contribute to fuelling tensions in collaborative practices across sectors. To compensate for the inadequate information and gain deeper insights beyond what was conveyed in written form through EHR systems, HNs and CNs resorted to direct verbal communication via telephone (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Foged et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2019), particularly in more complex cases (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Lundereng et al, 2020).

CNs emphasised the importance of meaningful dialogue through direct communication and stressed how the tone used in this communication would either facilitate or impede their collaborative efforts (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Petersen et al, 2019). When receiving telephone calls from CNs, HNs typically found themselves unprepared and preoccupied with other tasks, making them appear distant in their tone of voice and unable to fully embrace the spirit of collegiality extended to them. This limited their ability to meet CNs' information needs (Petersen et al, 2018). Accordingly, CNs experienced feelings of rejection and frustration when seeking further information even though the HNs did not intend to convey such feelings (Foged et al, 2018).

Accordingly, a pleasant, respectful and welcoming tone used during direct contact promoted a sense of collegiality and stood out as an important factor in fostering successful collaboration (Lemetti et al, 2017; Foged et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2019). Conversely, the use of an unfriendly tone would contribute to distrust and distress for both parties, possibly culminating in increased tension (Foged et al, 2018).

Thus, a negative tone in verbal communication characterised by absence of collegiality held potential to fuel tensions in cross-sectoral communication as CNs perceived this as low engagement in their intraprofessional collaborative efforts.

Different care perspectives: engendering a battlefield

Feelings of mutual distrust towards one another's knowledge and competencies resulting from different perspectives on and approaches to patient care had the potential to fuel tensions and amplify distances in collaboration between CNs and HNs. This occurred, among other times, when HNs expressed distrust towards CNs' knowledge and competencies, in particular expressing concerns about how patients would manage after discharge (Lundereng et al, 2020). CNs expressed that they occasionally perceived HNs to adopt a stance of superiority, manifested through their questioning of the information about the patient's habitual physical condition provided by CNs when patients were hospitalised (Olsen et al, 2013). However, the lack of confidence in the information exchanged was mutual, as CNs also expressed distrust towards information conveyed by HNs, sharing equivalent concerns about how the older patient was cared for during hospital admissions (Kirsebom et al, 2013; Olsen et al, 2013; Petersen et al, 2018; Petersen et al, 2019; Lundereng et al, 2020).

HNs emphasised their perception of themselves as specialists within their medical field, whereas CNs regarded their approach as holistic, embracing the patient's whole situation. These different perceptions and care approaches within each organisation would distance the two parties from each other, contributing to creating a relationship characterised by an ‘us versus them’ dynamic (Olsen et al, 2013), also described as working in ‘two worlds’ (Petersen et al, 2019). This distance in the collaborative relationship, coupled with the contrasting patient care approaches, has the potential to engender a metaphorical ‘battlefield,’ emblematic of the struggle to reach consensus, thereby fuelling tensions within the collaboration.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight that collaborative practices in older patients' discharge processes were multifaceted, with several intertwined aspects, particularly related to communication and information exchange, having the potential to create tension in the collaboration between HNs and CNs. The findings of this study stressed that cohesion between CNs and HNs was undermined by a lack of knowledge of information needs of and resources available to the nurses in the opposite sector. This would give rise to breakdowns in and withdrawal from intraprofessional collaboration because of miscommunication and distrust. Furthermore, negative assumptions about HNs' willingness to collaborate and exchange adequate information with CNs inevitably impacted the transitions, establishing a ‘negative loop’ that ultimately fostered tensions. This negative loop consisted of feelings of unequal consideration of each others' needs and a lack of confidence in each others' competencies, which triggered a latent battlefield in which the CNs frequently felt that the HNs considered themselves to be superior. Similarly, in a scoping review of collaboration among HNs and CNs when transitioning older patients, the authors stressed that hierarchical relationships in which HNs perceived themselves as more competent than CNs was a source of conflict that affected collaboration negatively (Moore et al, 2021).

The present study adds to the dual role of communication as both a facilitator and a barrier (Norlyk et al, 2020; Moore et al, 2021) by explaining how the categorised and predetermined nature of the EHR systems could act as a barrier, forming an ‘invisible wall’ in cross-sector communication by offering only fragmented information. This ‘invisible wall’ would further exacerbate tensions related to the credibility of information, implicitly questioning the credibility of the nurses from the opposite sector. Conversely, a morerecent study showed that using direct contact in the form of telephone calls may produce a sense of security among HNs as they had the opportunity to provide more comprehensive information than when communicating in writing and had confirmation that the information they provided was received by the responsible CNs (Winqvist et al, 2023). This study adds to these findings by demonstrating that whereas direct contact in the form of phone calls was initiated to obtain detailed information in more complex patient cases, the tone of voice adopted during these phone calls strongly influenced the collaboration between HNs and CNs. Thus, an unpleasant tone could signal hierarchal relationships, thereby creating interpersonal tensions. Consequently, rather than fostering collaboration between the two care contexts, tensions arising during the patient discharge process would distance CNs and HNs further from each other, potentially positioning them as opponents rather that collaborators.

As the intraprofessional collaboration between nurses is predicated on a non-hierarchical relationship and rooted in relational and interactional processes (Ylitörmänen et al, 2019), it is concerning that the distance between HN and CN may erode the robust collegial bond that should ideally exist. As shown by the findings of this study, the growing distance between the nurses may result in low levels of mutual recognition, limiting the potential for cohesive intraprofessional collaboration. These shortcomings in intraprofessional collaboration are concerning as studies have shown that they potentially cause troubling outcomes by increasing older patients' risk of readmission and limiting their general experience of continuity of care when discharged from hospital to homecare (Elkjær et al, 2023).

Lastly, these findings stressed how intermediate links in nurses' cross-sectoral communication were created when passing discharge planning responsibility to colleagues. This passing of responsibility would potentially reduce the credibility of the information exchanged to CNs as it rarely met their information needs. Based on these findings, the authors' raise concerns about the ongoing efforts to introduce transitional care nurses within the organisation (Møller et al, 2023). According to these findings, this may potentially increase the perceived distance between the nurses rather than promoting their collaborative efforts. Furthermore, critical information about the older patient may be lost in the discharge process as a result of reduced information credibility. However, successful collaboration between HNs and CNs was described to require organisational support, including mutually agreed objectives, policies and guidelines (Lemetti et al, 2021).

Strengths and limitations

The meta-ethnography approach allowed the authors to translate the perspectives of intraprofessional collaboration among HNs and CNs, presented in other qualitative studies, into a reinterpreted description of conflictual collaboration practices that carried the potential to undermine cohesion between the CNs and HNs. The majority of the studies included in this paper were conducted the Nordic countries. Three papers were from Norway, three from Denmark, one from Sweden and one from Finland. The Nordic countries have similar welfare systems in which services are mostly financed through taxes, with a primary aim of ensuring equal access to healthcare services for all. Only one of the included papers was from the US. As the organisational structure of discharge processes and homecare services in the US vary considerably from those of the Nordic countries, a greater representation outside the Nordic countries would have strengthened the applicability of the findings.

Conclusions

The study stressed that several collaborative practices could fuel tensions between HNs and CNs during older patients' discharge process. These tensions caused concern as they might distance CNs and HNs from each other, impeding mutual collaboration based on equal and non-hierarchical relationships. Tensions then forged a negative loop in which the nurses potentially emerged as opponents rather than as collaborators. The causes of the negative loop established during older patients' discharge process are complex and resolving these issues demands the attention of the involved organisations.

This study stressed that support from both organisations in terms of shared policies and mutually agreed cross-sectoral objectives carry the potential to interrupt the negative loop described. A need exists to raise awareness among policy makers and managers of tensions in the collaborative practices rooted in problematic cross-sectoral organisational structures.