People living with stoma face many barriers as they try and adapt to life with a newly formed stoma. This article explores these issues to enable the community nurse to better assist people in the community living with a stoma.

There are three main types of output stoma: colostomy, ileostomy and urostomy (White and Perrin, 2023). A colostomy is formed from the colon and will usually pass flatus and thick, formed faeces once a day (Stelton, 2019). Thus, the most appropriate stoma appliance to use is a closed appliance. A closed appliance is usually replaced between three times a day and three times a week.

An ileostomy is formed from the ileum and will usually pass flatus and loose or porridge-like faeces. The average ileostomy output ranges from about 500–800 ml daily and requires the appliance to be emptied on average four to six times daily. Thus, the most common stoma appliance used is drainable with a velcro type fastening.

A urostomy is formed from a segment of bowel, usually the ileum, which is joined at one end to the ureters from the kidneys. The other end is the urostomy on the abdominal surface. A urostomy will pass urine and small amounts of mucus produced from the segment of bowel. While the volume of urine will vary, it is generally about 1000 ml daily. The most useful stoma appliance in this case is a drainable device with a tap or bung type fastening.

Barriers to adaptation

One barrier to adaptation is a lack of knowledge or confidence about living well with a stoma. The community nurse can assist by increasing knowledge as well as supporting and providing advice to this group of patients. The community nurse can also signpost patients to support groups locally or nationally.

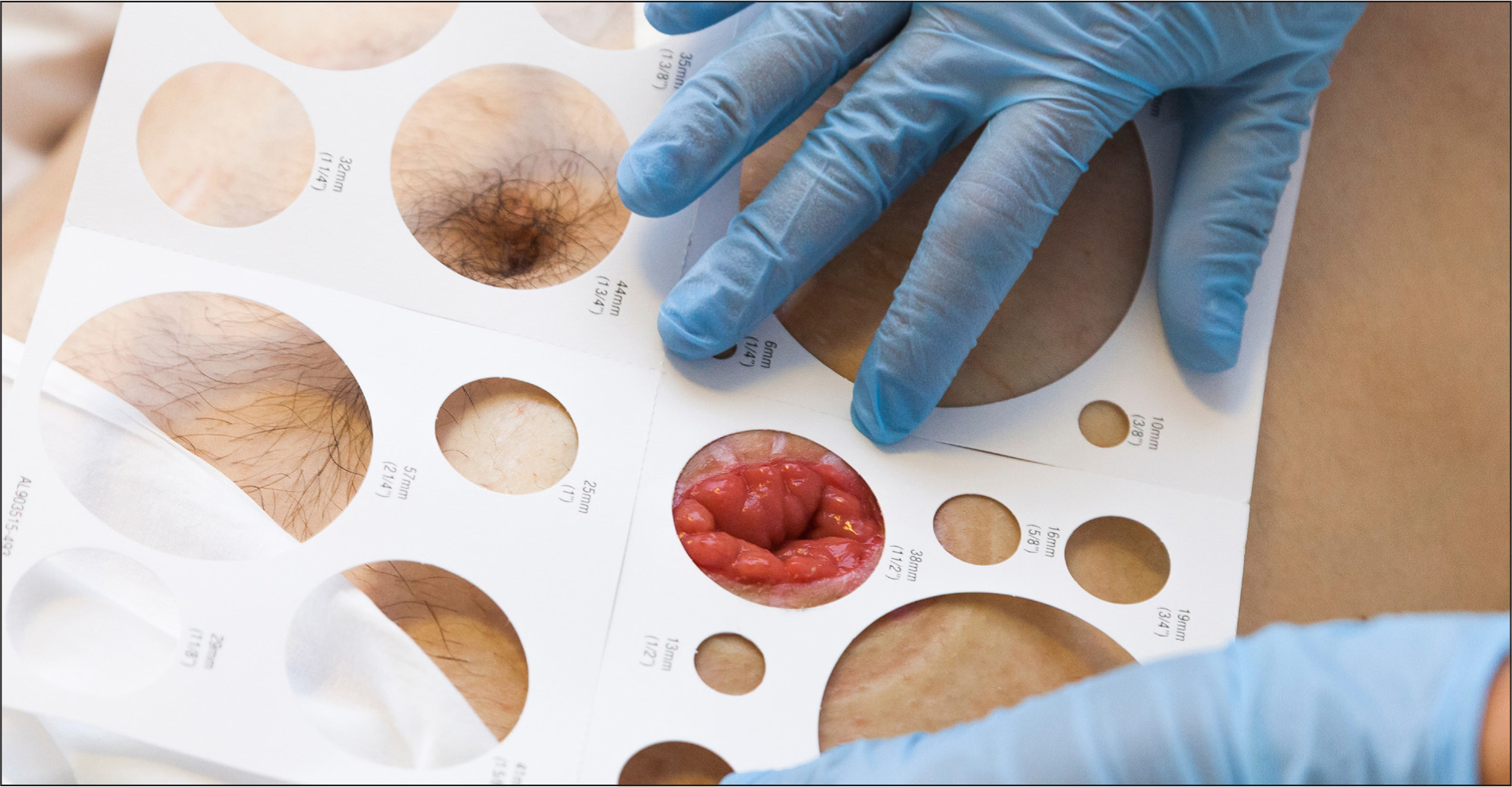

When returning home from the hospital, the patient with a newly-formed stoma will have been taught how to undertake the basic stoma appliance change routine (Steinhagen et al, 2017). They will also know how to collect all the necessary stoma change products, such as a clean appliance, tap water and cleaning cloths (Ratliff et al, 2021). The hospital staff will also have taught them how to carefully remove the appliance, how to clean and dry the peristomal skin (skin around the stoma) and how to assess the size of the aperture needed in the stoma adhesive flange. The ideal aperture size is about 2 mm larger than, but the same shape as, the stoma.

Carefully assessing the stoma size is important in the first 8 weeks after the formation of a new stoma (Figure 1). The stoma will reduce in size during this time because of the reduction of postoperative oedema. If the patient does not measure their stoma at least once a week in the first 8 weeks, there is a high probability of the peristomal skin becoming damaged. The patient might report this to the community nurse as discomfort associated with skin damage or bleeding. The community nurse should ask the patient to remove the appliance and monitor the patient to confirm that they are not causing skin damage by using excessive force when removing the stoma appliance. Peristomal skin damage caused by the resolution of postoperative stoma oedema often presents as a circle of skin damage around the stoma. In this scenario, the community nurse should once again explain to the patient how to use the stoma template to ensure that patients measure their stoma accurately and cut the aperture to the correct shape and size.

Another barrier to adapting to life with stoma is not having the correct stoma appliance. The stoma care clinical nurse specialist available in the local hospital is usually best placed to provide advice on stoma products. Products might not be used effectively if people forget the guidance on how to manage their stoma. The community nurse may become aware of this by recognising the signs, such as a person living with a stoma requesting an above-average amount of stoma products. This could potentially indicate a problem, such as frequent stoma leakage, and would require careful assessment by the community nurse to determine the cause and management strategy.

Lack of social adaptation might become obvious to the community nurse if the person living with a stoma avoids leaving the house. The community nurse can support the patient to recognise that living with a stoma should not prevent social activities. There may be several reasons that a person will not leave the house, such as fear of the stoma being noticed by others (Cengiz and Bahar, 2017) or fear of the appliance leaking (Krogsgaard et al, 2022). The community nurse can be supportive and encourage short trips out to build confidence. In cases where the patient is not adapting well to their stoma, their mental wellbeing needs should be addressed. This is a common occurrence in the first few months after a stoma formation as the person goes through an adaptation phase. For people who are not leaving the house or becoming withdrawn, additional assistance, such as counselling, may be necessary to support the person to cope with their stoma.

Another barrier to adapting to life with stoma is not knowing which physical activities are allowed. The community nurse can provide support and advice in this situation to help them get back to normal activities and diet. There is evidence that people become less active after a stoma formation for fear of damaging their stoma, or because of concerns about developing a parastomal hernia. The community nurse can advise that it is unlikely for a stoma to be damaged by activity and many activities can gradually be increased over the first 3 months after the stoma is formed.

Walking is advised as soon as the person is discharged home from the hospital and the distances walked can be gradually increased. Resuming work inside the house, the garden or paid employment will vary, depending on recovery after surgery as well as the nature of the work. Light duties can be quickly resumed, with more frequent rests than before in the initial few weeks. Returning to paid work is often benefitted by a phased return and lighter duties initially. Gardening activities can be resumed quicker for gentle pruning and weeding, and slower for pushing the lawnmower and digging. There is some evidence that careful undertaking of abdominal exercises to strengthen the abdominal muscles, possibly with the use of a support garment, can assist in preventing a parastomal hernia.

Dietary advice

While dietary advice is frequently requested by patients, there is limited evidence to support the advice given (Mitchell et al, 2021). It is generally considered that in the first few weeks, up to about 8 weeks, all people with a stoma need to be mindful of their dietary choices. This is necessary because the bowel used to create the stoma will have oedema and food is likely to cause problems until the swelling resolves.

In the longer term, there is limited dietary advice for people with a colostomy. Most people can return to their normal diet. For people who were prone to constipation before stoma formation, advice may include a gradual increase in fibre content, oral fluid intake and mobility.

People living with a urostomy need to ensure that they consume about 1500 ml of liquids per day. They should also be advised to note any changes in urine colour and to drink more water if they notice darkening of urine. Patients also need to note changes in smell and report them to the clinical nurse specialist stoma care or general practitioner, as this could indicate a urinary infection. An increase in the amount of mucus seen in the urostomy appliance might also indicate a urinary infection. There is limited evidence to suggest that drinking cranberry juice every day can help to keep the mucus levels low.

People living with an ileostomy generally make the most changes to their dietary intake. There are a number of reasons for this: a) the diameter of the ileum is narrower than that of the colon and it is more prone to blockage and b) the consistency of the faeces is looser than for a colostomy and there is a higher risk of dehydration or appliance leaks occurring. Advise the patient to carefully chew food to avoid blockage of the ileostomy. This is particularly important for foods that are difficult to digest such as high-fibre foods.

To prevent dehydration, it is important to drink at least 1500 ml of fluids daily and consider limiting high-fibre foods, as they can speed up bowel movements and reduce the time available for fluid absorption in the gut (Liu et al, 2021). Instead of limiting diet, it is also possible to take loperamide to thicken the faeces and slow down bowel transit. While some people choose to exclude certain foods from their diet, this should to be done with caution to avoid the risk of not having a balanced diet. They might need the assistance of a dietitian if other conditions requiring dietary restrictions exist, such as diabetes.

Conclusions

The community nurse is well placed to assist the person with a stoma to adapt to their new lifestyle. Simple advice and encouragement can increase confidence for the patient. It should also be remembered that the clinical nurse specialist stoma care is available in hospitals for more specialist advice.