This article follows up on a previously published article exploring the specific needs of ileostomy patients (Marinova and Marinova, 2024b). It explores in detail the colostomy patient-specific domain that healthcare professionals must be educated on to ensure patient care is delivered appropriately. The next article in the series will explore the urostomy personalised stratified follow-up pathways.

A stoma is a surgically created opening in the abdomen that allows for the diversion of faeces or urine outside the body (Marinova et al, 2021). Stomas come in different types, with the three main types being ileostomy, colostomy and urostomy, which can be temporary or permanent. All stoma patients need life-long support with their stoma care, and colostomy patients have unique needs that necessitate specialised care pathways for optimal outcomes. Many areas in the UK provide stoma patient pathways to ensure that support is offered to these patients (Davenport, 2014; Bowles et al, 2022; Marinova and Marinova, 2023). However, these pathways are not universal and may vary depending on the area. Furthermore, these are usually generic and not patient-specific, as they do not define the specific needs of patients based on the type of stoma they have—colostomy, ileostomy or urostomy. Therefore, it is essential to recognise that these needs differ based on the stoma's type and configuration, and customising these pathways for colostomy patients can help prevent complications, reduce hospital readmissions and improve quality of life. Community nurses and other healthcare professionals play a vital role in delivering individualised care to ostomates. Their involvement ensures that patients are well-prepared for life with a stoma and that their specific needs are met consistently. This multidisciplinary approach creates a comprehensive care environment, addressing the physical and emotional aspects of living with a colostomy.

Educating patients and healthcare professionals on stoma-specific care should be a priority to ensure optimal outcomes. Traditionally, this education is predominantly delivered by stoma specialist nurses, who support the educational needs of healthcare professionals in primary, secondary, community and tertiary care (Marinova and Marinova, 2024a). This ensures that all healthcare professionals possess the necessary skills to provide adequate care for stoma patients and help educate them about best practices for their stoma care routines.

Stoma nurse specialists also educate patients and their carers but rely on all healthcare professionals to support stoma patients during their learning process. If patients do not fully understand the education and advice given during the immediate preoperative and postoperative periods, they may face difficulties managing their stoma, both in the hospital and after discharge. This is why it is important that healthcare professionals in the primary and community care settings are able to support their needs. Tailored education and care are essential, especially in the first few months post-operatively, to help patients achieve independence and self-care. Failure to address stoma-specific needs can lead to avoidable complications and even hospital admissions. This aligns with the trend towards personalised, stratified follow-up pathways (Røsstad et al, 2013; NHS England (NHSE)and NHS Improvement (NHSI), 2020).

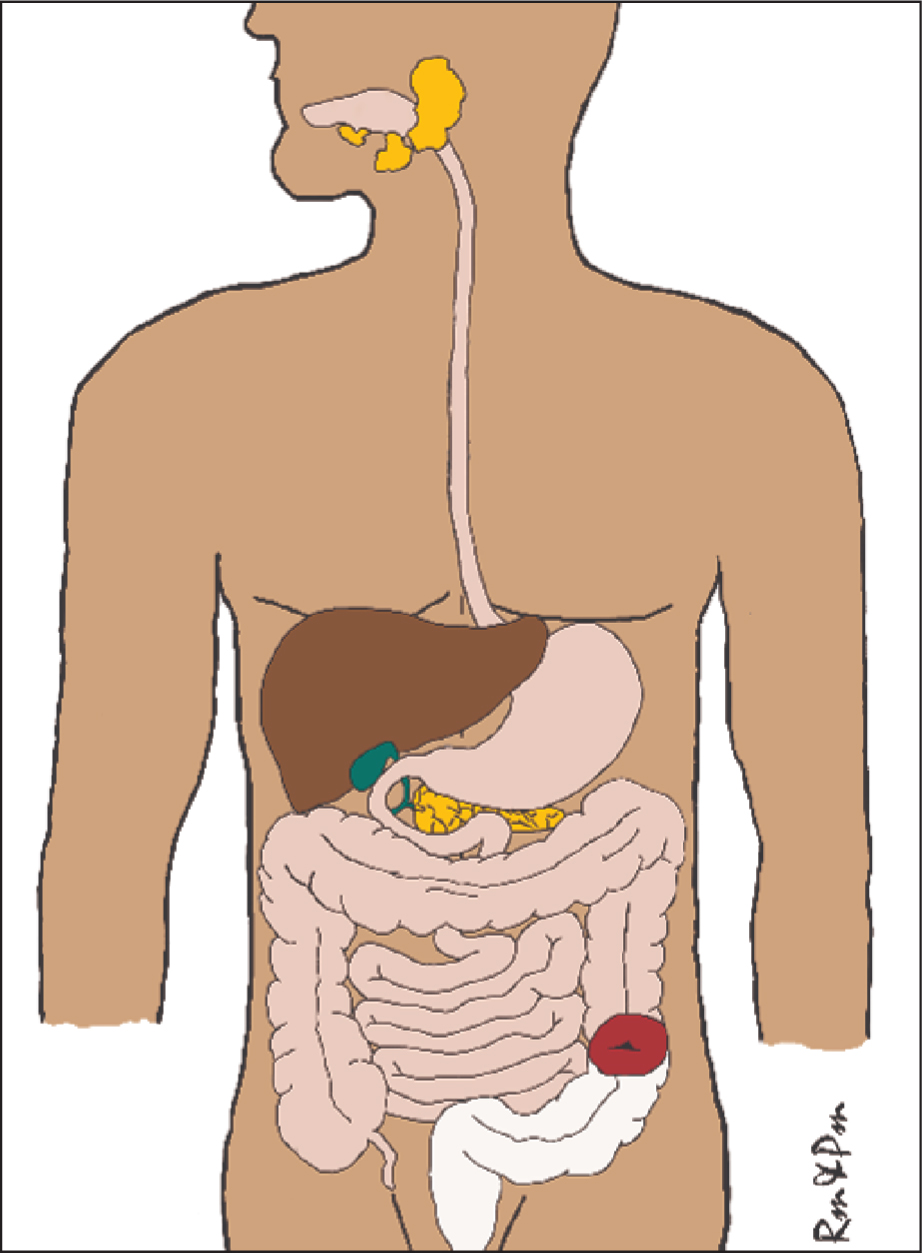

A colostomy is created from the large intestine and can be made from any section of the colon—ascending, transverse, descending or sigmoid colon. Depending on how far down along the colon a colostomy is formed, the possibility of stool being more formed will increase, as the large intestine is still part of the digestive process, especially the absorption of water, salt, and some nutrients, including vitamins and fatty acids. However, if a colostomy is at the first part of the colon (ascending colon), absorption may not be as optimal and therefore, the stoma effluent (output) may be semi-liquid and more like an ileostomy (typical ileostomy output is 600-800 ml/day). Nonetheless, most colostomies are performed at the last part of the colon (descending or sigmoid colon) and the output is usually semi-formed (Marinova et al, 2021; Hedrick et al, 2023).

Approximately one in every 335 people in the UK has a stoma (Colostomy UK, 2022), or around 205 000 ostomates (Marinova et al, 2021; Aibibula et al, 2022). In the UK, colostomies are generally more prevalent than ileostomies (Mthombeni et al, 2023), primarily because an ileostomy is more likely to be temporary, as they are often performed to allow the colon to heal after surgery. In contrast, a colostomy is more likely to be permanent, especially in cases where a portion of the colon and/or the rectum is removed and cannot be reconnected. Colostomy patients are generally not at risk of dehydration, and therefore, if a permanent stoma is required, where possible, a surgeon would normally prefer a colostomy, to reduce some complications specific to ileostomy—dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, higher risk of peristomal skin complications.(Ge et al, 2023; Parini et al, 2023). Therefore, it is estimated that there are over 120 000 patients with a colostomy, with roughly 11 000 new colostomies each year in the UK (Fellows, 2017; Lister et al, 2020; Coulter, 2022).

While colostomy patients do not usually have as many severe peristomal skin complications, (Taneja et al, 2017; Salvadalena et al, 2020), they face their own challenges. If a colostomy is formed from the first part of the colon and its output is semi-liquid, complications including skin complications will be more likely to occur.

Additionally, patients with an ascending or transverse colostomy are more likely to be readmitted within 30 days, when compared to those with a descending or sigmoid colostomy. This is mainly because they may have high-output stomas and dehydration (Cox et al, 2023). Therefore, healthcare professionals must be careful not to generalise all colostomy patients. Though most of them have relatively formed output, some may have high-output stomas as a result of the anatomy and physiology of their colostomy (eg ascending or transverse).

To ensure that colostomy patients receive adequate support after discharge and to avoid unnecessary hospital visits or appointments, it is crucial they have immediate access to specialist services managed by stoma care nurses (Royal College of Nursing, 2009; Davenport, 2014; Carter, 2020). Many stoma care services offer advice lines that provide timely assistance, ensuring that the patients are well-supported. However, these services are typically available only during weekdays and office hours (09:00—17:00), leaving patients without specialist support during off-hours. Therefore, educating both patients and community healthcare professionals is essential, so that they can effectively manage colostomy complications. Many stoma nurse specialist services provide training for community colleagues; alternatively, many stoma manufacturing companies organise different study days and training as well.

With these goals in mind, the authors have developed strategies to equip patients for life with a colostomy, focusing on minimising complications and hospital readmissions by educating patients and healthcare professionals.

There are various options to ensure patients are well supported, such as the use of tutorials and written information. To address the issue of accessibility and to prevent information from getting lost, the authors provide patients with a comprehensive guidebook titled Stoma Care–A Guide For Patients (Figure 1). This book contains all the essential information on diet, hydration, managing complications and lifestyle advice. It is given to patients before surgery to keep at home, ensuring that all the relevant information is consolidated in one place, avoiding the need for multiple leaflets that can easily be misplaced (Marinova et al, 2021). Patients are guided to the sections pertinent to their specific needs, such as colostomy, to ensure that they fully understand the tailored advice.

Nevertheless, the book is not a replacement for specialist care; it is there to guide them. Patients still require life-long support with their stoma care. Additionally, it is essential to support general practitioners and community services to facilitate a seamless transition from secondary to community and primary care. They need to be equipped with the necessary knowledge to identify the unique needs of stoma patients, recognising that these needs vary significantly among the three main types of stomas.

Post-operative recovery

Patients are usually discharged before they are fully recovered and ready to resume normal activities. Whether this includes physical activities or return to daily routines and work or school, the support of primary and community care healthcare professionals is essential, as they are likely to review these patients more regularly than their stoma nurse specialists. It is important to know that patients are usually advised to resume physical activity immediately post-operatively, while still in the hospital, and then asked to gradually increase activities duration and intensity daily, as tolerated. The primary goal is to ensure that every patient returns to the lifestyle they had before having a stoma, as much as possible.

Usually, patients are advised that once they can go for a 30-minute walk, they can progress to more intense activities. However, when advising patients to maintain physical activities, especially returning to their hobbies, sports and activities of daily life, they must also be educated on hernia prevention. Patients should be encouraged to lift using the correct posture, keeping their back straight, using their leg muscles and not their back when lifting, and keeping the item they lift close to their body.

The use of support belts may be beneficial, especially if they engage in activities requiring heavy lifting, carrying or pushing heavy items. It is important to remember that everyone recovers at their own pace, and therefore, patients should not be generalised. While they must be encouraged and assisted to regain autonomy, continuous assessment of their functional needs is essential.

It is fundamental to also assess their manual dexterity and any signs of cognitive issues, as these may affect their stoma care. Adjustments such as using pre-cut stoma bags or training a family member or a carer can help greatly improve these patients' care.

Diet with a colostomy

Having a colostomy is a life-changing surgery, performed to save or improve patients' lives. It is common for patients undergoing emergency surgeries to have colostomies formed, usually Hartmann's procedure, resulting in end colostomy (Qureshi et al, 2018). This may put patients in a situation where post-operatively they may need longer to recover, as a result of being critically unwell and requiring emergency surgery. As such, lifestyle adjustments are essential, to ensure that these patients adapt to the physiological changes in their lives. Misconceptions related to the colostomy diet may lead to preventable complications, including constipation, ballooning, pancaking and stoma appliance leakages (Marinova et al, 2021; Burch, 2022). As part of colostomy patients' personalised stratified follow-up pathways, they must be educated that they need to avoid certain foods (usually temporarily) for the period immediately after surgery. A few weeks post-operatively, they can start introducing foods from the avoid list, such as spicy, high-fibre and deep-fried foods. See Table 1 for a list of foods patients are advised to include or avoid in the immediate post-op period after colostomy surgery. It is important to note that if a patient has an ascending or transverse colostomy, then the advice will be to avoid problematic foods up to 6 weeks after their colostomy-forming surgery and be mindful of their effect in the long term. This is to ensure that common complications, such as high output and dehydration, can be avoided (Burch and Black, 2017; Marinova et al, 2021). A typical colostomy patient will be advised to return to their normal diet within a few days to a few weeks after surgery.

| Foods that may make output thicker or more formed | Foods that may make output looser or cause excessive flatus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

An average colostomy output is 200-500 ml/24 hours, depending on the type of colostomy (eg ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid), diet, hydration, medication history and underlying conditions. Most colostomies are from descending or sigmoid colon, and therefore, a typical colostomy usually has a semi-formed or formed output, and fluids and minerals are absorbed, with output likely to be in the lower average range (eg 200 ml). It is unusual for colostomy patients to have concerns about electrolyte imbalances or malabsorption. However, with an ascending or transverse colostomy, mineral losses may be more likely and the patients may have to modify their diet and include more salt, if appropriate. Some colostomies may not produce stoma effluent daily, so it is paramount that both patients and healthcare professionals are taught to differentiate between constipation and obstruction in colostomy patients. Prolonged periods (24-48 hours) without stoma effluent may be normal, but this often alarms patients and healthcare professionals, who may incorrectly believe it is because of a bowel obstruction. Patients and healthcare professionals must be educated that, unlike ileostomy patients, whose stoma continuously produces effluent, the colostomy may not produce any stoma output for 24 hours or more, which is normal. If there are no signs or symptoms suggestive of bowel obstruction (bloating, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, pain etc) patients should be reassured and prevention and management of constipation advice should be given instead.

Constipation in a colostomy patient may present as bloating, feeling full, reduced appetite, abdominal discomfort and reduced, constipated or hard stool. Oftentimes, colostomy patients may struggle with constipation because of a lack of fibre in their diet and insufficient hydration. Patients and healthcare professionals should be aware that, while it is generally recommended to avoid certain foods during the first few days or weeks after colostomy surgery, a normal healthy diet must be adopted afterwards. These foods can be gradually reintroduced after the initial post-operative recovery period. Most colostomy patients should be able to resume eating a normal diet without restrictions. After the initial period of adaptation, colostomy patients are encouraged to have a high-fibre healthy diet, to ensure constipation or similar diet-related complications, such as pancaking and ballooning, may be avoided.

Pancaking is a relatively common occurrence for upto 80% of colostomy patients (Perrin et al, 2013). It happens when the colostomy output is thick and sticks to the top of the stoma bag, and does not drop to the bottom. This can become frustrating as it may cause the bag to lift off the skin, as well as premature detachment of the bag. Pancaking could also lead to sore skin as stoma output may sit on the skin. All of these contribute to a poorer quality of life for colostomy patients. The most common reason for pancaking is the lack of air in the bag, creating a vacuum or the output being too thick. Patients will be advised to adhere to a high-fibre diet and increase fluid intake. Lubricant, such as cooking oil, can be added inside the stoma bag to prevent the inner lining from sticking. This will assist the thick output in dropping down to the bottom of the bag, and not sitting on top and around the stoma.

Ballooning is also very common for colostomy patients (Virgin-Elliston et al, 2023). It occurs when excessive flatus (wind) accumulates inside the stoma bag and the built-in filtering system of the bag is not able to expel it through its carbon filter. This usually happens if the patient consumes excessive amounts of foods and drinks known to cause flatus (fizzy drinks, cruciferous vegetables, pulses etc). Additionally, ballooning may occur if the stoma bag is not changed regularly and the filter loses its ability to filter efficiently, usually lasting 12-24 hours. Another reason may be a malfunctioning filter or inefficient filtering system used by the manufacturer. In these cases, the patient may need to either change their stoma bag more often, look for a different type of bag (a different brand) or switch from a 1-piece to a 2-piece bag. A stoma nurse review would be required.

Although colostomy patients typically receive dietary guidance during pre-operative counselling and post-operative care, many tend to forget or only vaguely remember the information once they return home (Kessels, 2003). Thus, it is crucial for healthcare professionals who care for these patients to be knowledgeable about their specific dietary requirements, enabling them to reinforce the dietary advice as necessary. However, when colostomy patients are unwell, whether because of a cold, flu or other issues, these conditions can alter their colostomy function. In such cases, patients may need to temporarily switch to a diet of bland, low-fibre, non-deep-fried and non-spicy foods while they recover. It is crucial to treat each patient as an individual and inform them that different foods can have varying effects on their colostomy.

Hydration with colostomy

Typically, colostomy patients are advised to drink plenty of fluids (1.5-2 litres/day) to avoid complications such as constipation and pancaking. Generally, colostomy patients are not at risk of dehydration, unless their colostomy output is high. In the rare event of high-output colostomy (eg ascending/transverse colon, or other co-morbidities), Table 2 provides examples of fluids that patients should be careful of when managing complications, such as dehydration, constipation and pancaking. It is important to remind colostomy patients that consumption of alcohol may contribute to looser and increased output, if not consumed in moderation.

| Drinks that do not usually affect output or flatus | Drinks that may cause increased output or flatus |

|---|---|

|

|

As constipation and pancaking are of concern in colostomy patients, they are encouraged to have drinks that help manage and prevent constipation, for example, have 1.5-2 litres of fluids, including coffee, prune juice etc. To empower patients to manage their condition independently, it is essential to educate them as part of patient-centred followup pathways. This education should prepare, recognise and address constipation promptly. Additionally, if patients find it challenging to manage this independently, their families, carers and other healthcare professionals should also be educated to provide the necessary support.

Ballooning is another common complication and therefore, an important part of hydration for colostomy patients is to ensure that there is awareness of drinks that may cause increased wind, such as fizzy drinks, milkshakes and some juices. This ensures that patients have realistic expectations when choosing what to drink, especially if the colostomy patients struggle with excessive wind and ballooning.

Medications

Another important element of colostomy patient-centred followup pathways is ensuring that these patients have a good understanding of medication management specific to their condition. One of the most common issues that colostomy patients may encounter when using medications is constipation. Medications that may cause this include some iron supplements (known to harden stool) (Smith et al, 2019; McDonald et al, 2022), blood pressure and heart medications, opioids, antidepressants and antiacid medications. In such cases, patients must be educated to expect that their colostomy function may be reduced. Increased fibre intake, plenty of fluids (if appropriate), adequate exercise and, in some cases, the use of laxatives may be recommended (Burch and Black, 2017; Marinova et al, 2021).

It is common for colostomy patients to use laxatives, which may be advised as a treatment for constipation. As part of physical assessment and history taking, clinicians should always establish what the patient's normal bowel movement pattern was before stoma formation. Patients who have a history of constipation and slower bowel transit before surgery are likely to have similar function with their colostomies.

Some medications may cause loose or increased output in colostomy patients. These include antibiotics, laxatives, metoclopramide, metformin, magnesium-containing medications and supplements, and chemotherapy drugs. Patients and healthcare professionals must be aware of this so that they can effectively manage the effects. In some cases, patients may benefit from switching to a low-fibre diet or taking anti-motility drugs, such as loperamide, if appropriate. Colostomy patients do not typically encounter issues with modified-release medications, unless they have an episode of high-output stoma, or they have an ascending or transverse colostomy, in which case absorption may be altered. Ensuring that patients and healthcare providers are aware of these potential issues can help in making informed decisions about medication management and maintaining effective treatment outcomes.

Routine tests

Most colostomy patients have the majority of their digestive tract in use (Figure 2) and are not normally prone to vitamin and mineral losses, so there are no recommendations for routine tests. Colostomy patients are advised to have the same routine tests as any other person, as part of best practice. However, if patients have an ascending/transverse colostomy, their routine tests, including electrolytes, essential vitamins and minerals, are normally requested by the GP to ensure any deficiencies are caught on time and treated accordingly.

Stoma appliances and accessories

Many NHS organisations and regions advocate for the use of formularies and prescription guidelines for stoma care products. Typically, colostomy patients are advised to use between 30-90 closed stoma bags or 10-30 drainable stoma bags per month, depending on how frequently they need to change their bags. This frequency can range from 1-3 times a day to once every 1-3 days (PrescQIPP, 2015; Marinova et al, 2021). As colostomy patients may need to change their closed colostomy bag up to 3 times a day, they may be advised to use a two-piece system (Figure 3), which allows them to keep the baseplate (the part that adheres to the skin) for 2-3 days and then change the stoma bag as required, by simply detaching the used bag and attaching a new one. Though not common practice in the UK, the authors' experience is that when colostomy patients are offered a two-piece system option, many tend to prefer it as it normally makes their stoma care easier.

Patients with newly formed or problematic stomas may require more products. Therefore, it is recommended that these patients have regular reviews of their stoma appliances and prescriptions by a stoma nurse, ideally 4-5 times in the first 6 months and then annually or more frequently, if needed. This ensures that patients receive adequate support and minimises waste. Patient-centred pathways are crucial to address individual needs and ensure that care is not compromised. Regular reviews and personalised care plans help in providing the necessary support and optimising the use of stoma care products.

Colostomy patients often face challenges, such as pancaking, constipation and ballooning, which can lead to increased leakage episodes. These issues significantly impact their quality of life and increase the costs associated with managing complications (Rolls et al, 2023). Therefore, frequent reviews by a stoma specialist nurse are often necessary. To manage pancaking effectively, it is advisable to consider lifestyle and dietary changes first. The use of convex stoma bag appliances may be a very good option, as convex bags are known to reduce the incidence of leakages and associated complications, thereby improving patient outcomes (González et al, 2021). Ensuring that patients receive regular reviews and appropriate appliance recommendations can help mitigate these issues and enhance their overall well-being.

Additional products such as stoma paste, seals and flange extenders, known as accessories, are not routinely prescribed and are typically reserved for patients experiencing complications. The use of these accessories depends on patient-specific needs, including the type of stoma (PrescQIPP, 2015; Marinova et al, 2021).

It is important to recognise that a single stoma bag or brand is not suitable for everyone. Thus, recommending a generic brand for all patients when using formularies is not appropriate. Stoma bags also function as skin care products, and stoma nurse specialists choose them based on each patient's unique needs.

Although formularies and guidelines typically suggest recommended quantities of products per month or year, these recommendations are influenced by many factors. Clinicians should be aware that formulary recommendations and prescription guidelines may not be suitable for all patients, particularly those with complex stoma needs. Additionally, some patients may use less than the recommended bags per month and this also must be assessed to avoid overprescribing. Therefore, healthcare professionals must consider all these factors when making prescribing decisions for these patients.

Colostomy irrigation

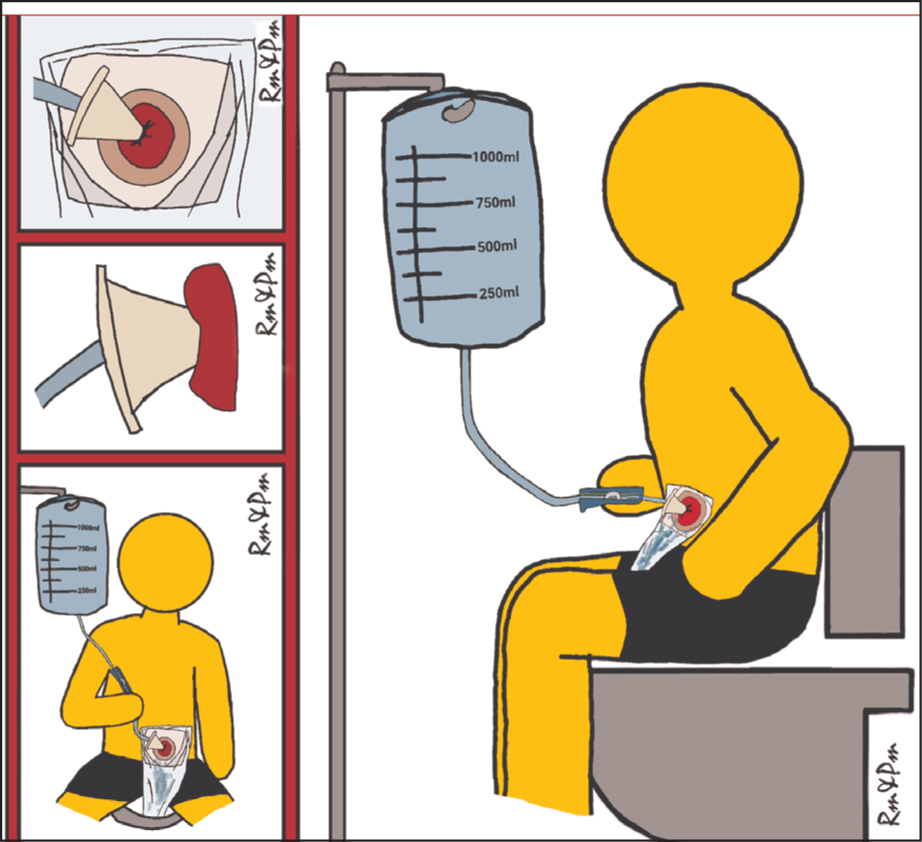

Colostomy patients have the unique possibility to use colostomy irrigation, which has the potential to decrease the cost of appliance use, improve their quality of life and overall improve their colostomy function (Boutry et al, 2021; Marinova and Marinova, 2024c). Colostomy irrigation (Figure 4) involves introducing water into the large intestine through the colostomy opening to aid in bowel emptying. The water stretches the intestine, triggering wave-like motions (peristalsis) that expel stool and flatus.

Colostomy irrigation may allow up to 72 hours without a bowel motion between irrigations, a level of control over the colostomy function and eliminate or reduce the need for a colostomy bag. It can also allow for the use of a discreet stoma cap, reduce odour and wind and enhance body image and confidence as a result. Furthermore, colostomy irrigation may alleviate anxiety, improve or prevent complications such as pancaking, constipation and ballooning, or peristomal skin irritation (Marinova and Marinova, 2024c).

Unfortunately, colostomy irrigation is not routinely offered to patients in the UK (Bowles et al, 2022), likely because of the limited resources, as training patients to perform the procedures may require up to 3 or more additional stoma nurse reviews, as well as regular followups that may result in up to 5-6 consultations with a stoma nurse, which may not always be possible. It may lead to stoma nurses not offering the procedure or not being experienced in training patients because of limited practice. Therefore, investment in the workforce must be a priority, to ensure colostomy patients are well-supported. Given the benefits associated with the procedure, patients must discuss the use of colostomy irrigation with their stoma nurse specialist.

Patient followup

Followup pathways for ostomates can vary across different regions but many follow a similar structure, emphasising the first three months post-operation, when patients are still adjusting to life with a stoma. During this period, more frequent follow-ups are provided. Based on the authors' tertiary experience with structured followups, patients benefit from intensified followups in the first 30 days post-operatively, with clinical reviews every 10-14 days, or more frequently if complications arise. The frequency of followups then decreases, with reviews at month 3, month 6 and month 12, eventually transitioning to annual followups (Davenport, 2014; Marinova and Marinova, 2023). While structured pathways are used they are not tailored for different stoma types and do not provide specific recommendations for various patient groups. The frequency of followups is influenced by how well the patients are adjusting to their colostomy, whether they encounter any complications or if they wish to explore different procedures like colostomy irrigation.

When planning workforce and workload, it is essential to account for the fact that colostomy patients may need more frequent reviews, including colostomy irrigation training. This requirement should be thoughtfully incorporated into annual workforce planning to ensure these patients receive adequate support.

Important considerations

Colostomy patients need life-long support throughout their journey with a stoma. It is crucial that stoma care services are readily available to provide this support and that other healthcare professionals are also equipped to assist in various healthcare settings. This requires investment in the NHS workforce and infrastructure, as well as standardised patient pathways to ensure consistent care regardless of the patient's location.

Having an adequate number of stoma specialist nurses is essential for delivering optimal care to colostomy patients. These nurses play a vital role in reducing healthcare costs, alleviating pressure on emergency departments and easing the burden on general practitioners and consultant clinics by independently managing stoma patients through nurse-led services.

Conclusions

Developing clear and structured pathways to guide patients and healthcare professionals through the perioperative journey of stoma-forming surgery is vital for ensuring high-quality patient care and positive outcomes. These pathways should be tailored to address the unique needs of different patients and types of stomas, promoting a more patient-centred approach and enhancing patient outcomes.

To achieve this, stoma care services must be well-resourced to provide life-long support throughout an ostomate's journey, allowing for procedures such as colostomy irrigation to be offered to all suitable patients. Currently, such crucial procedures for colostomy patients are rarely being offered because of workforce shortages. Additionally, healthcare professionals across all settings—primary, secondary and community—should be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to care for these patients effectively, thereby reducing complications and hospital admissions. By investing in these areas, we can create a supportive and efficient healthcare environment that improves the quality of life for colostomy patients and fosters positive health outcomes.

Key points

- Streamlining patients-centred colostomy specific needs pathways ensures patients have a safe transition from acute to community settings.

- Healthcare professionals in both acute and community settings should be equipped with knowledge to recognise the specific needs of colostomy patients ensuring that patients receive excellent care.

- Preparing patients for life with a colostomy is essential for empowering them to self-care and recognise early signs and symptoms of complications.

CPD reflective questions

- What is the importance of empowering self-care in stoma patients?

- What are the psychological implications for a patient with colostomy experiencing stoma complications and/or hospital readmissions?

- What are the cost implications when colostomy patients encounter preventable complications or are readmitted to hospital?