This article follows previously published articles exploring the specific needs of ileostomy and colostomy patients (Marinova and Marinova, 2024a; 2024b) and examines in detail the urostomy patient-specific domain and the appropriate knowledge that healthcare professionals must possess to ensure appropriate patient care.

Urostomy

A urostomy is a surgically created opening in the abdomen that redirects urine from the body. It can be temporary or permanent. The opening is made when the bladder has to be removed or bypassed, and urine has to be diverted outside the body (Burch and Black, 2017). There are several types of urostomies, including:

Ileal conduit

This is the most common type of urostomy, where a piece of the ileum is used to create a conduit that connects the ureters and subsequently divert urine through a stoma exteriorised on the abdomen.

Colonic conduit

It is similar to the ileal conduit, but in this case, a piece of the large intestine (colon) is used instead of the ileum to create a conduit to divert urine.

Continent urostomy

This involves creating an internal reservoir or pouch from a section of the intestine to collect urine instead of the bladder. The pouch is connected to a stoma and the patient can empty it by inserting a catheter through the stoma. There are different types of continent urostomies:

Cutaneous ureterostomy

The ureters are detached from the bladder and brought directly to the surface of the abdomen to form a stoma. This type is less common. The reasons for a urostomy vary, but some of the most common ones are:

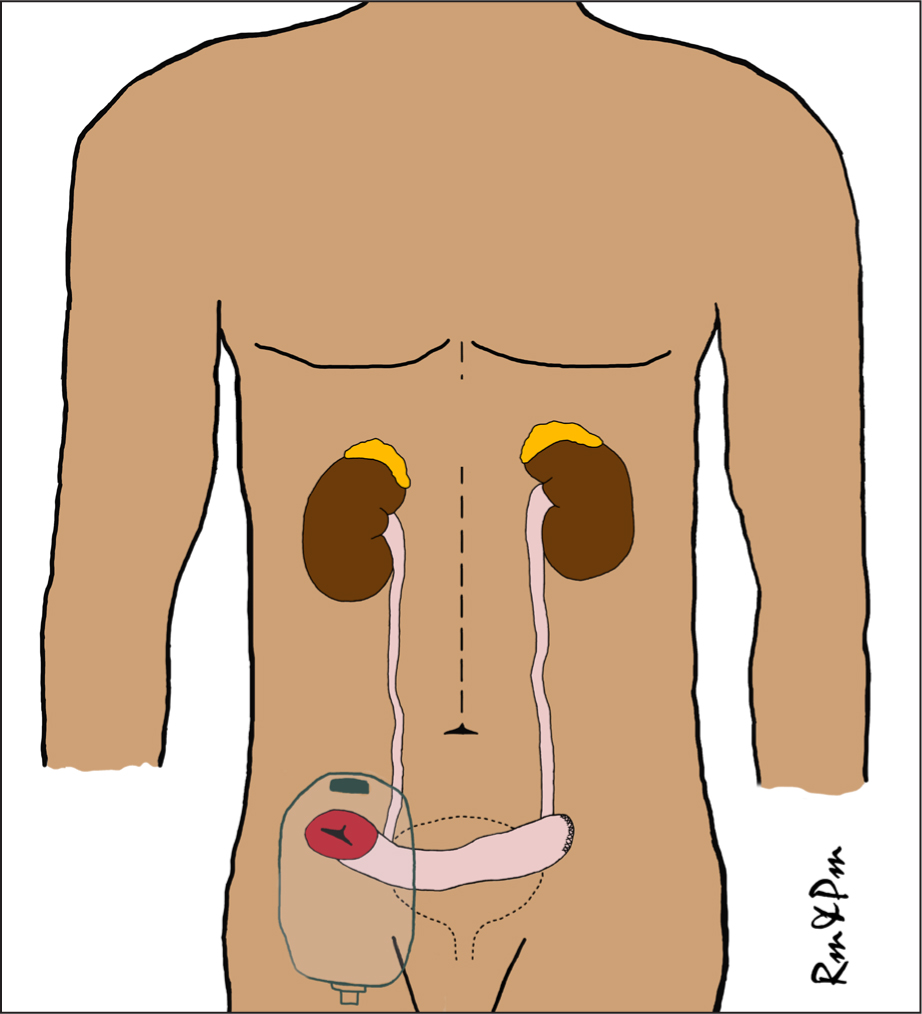

When talking about a urostomy, healthcare professionals normally refer to the ileal conduit as it is the most common urinary diversion (Figure 1). For the purpose of this article, the advice is for an ileal conduit, although most urostomies are similarly managed. Therefore, the advice is usually transferable. People with a urostomy require long-term care because their stomas are usually long-term or permanent. There are no established national patient pathways for stoma patients and care may vary (Davenport, 2014; Bowles et al, 2022; Marinova and Marinova, 2023; Rolls et al, 2024). Furthermore, where there are some generalised pathways, these are not usually tailored specifically to each type of stoma and do not reflect the fact that different types of stomas may require different follow-up pathways. This is why the needs of people with a urostomy must be well-understood by healthcare professionals across the primary, secondary and community settings to ensure that they are well supported. This is even more crucial for people with a urostomy because there are only around 11 000 in the UK, with an estimated 1000 new urostomies performed each year (Fellows, 2017; Lister et al, 2020; Coulter, 2022). This is approximately 10-12 times less than colostomy and ileostomy patients (Marinova et al, 2021; Aibibula et al, 2022).

Stoma nurse specialists are highly educated and skilled, dedicated to providing expert and evidence-based clinical and psychosocial care for stoma patients, as well as ensuring that they educate other healthcare professionals and families (RCN, 2009; Davenport, 2014; Carter, 2020; Bird et al, 2024; Rolls et al, 2024). Stoma care services' resources vary greatly across the UK; some offer advice lines that provide timely assistance ensuring that patients are well-supported. However, these services are typically available during weekdays and office hours (9am to 5pm) only, leaving patients without specialist support during off-hours. This is why the role of the stoma nurse specialist is very important in ensuring that urostomy patients are well supported. The absence of standardised stoma patient pathways, combined with a shortage of stoma nurse specialists, can leave urostomy patients struggling to find nurses experienced in providing the necessary care for their condition. In such cases, it is important that community nurses, who may care for patients who also have urostomies, have the knowledge to support patients with basic urostomy care needs and know when to escalate care to stoma nurse specialists to ensure that patients' care is not compromised.

Since urostomies are relatively uncommon, community nurses, doctors and other healthcare professionals may not be as familiar with the specific care needs of these patients. This is where the educational part of the role of stoma nurse specialists becomes very important as they are best placed to educate patients, carers, and community and primary care sector professionals to ensure that they contribute towards providing optimal care for urostomy patients. Educating patients and healthcare professionals on stoma-specific care and providing personalised patient-centred care results in better outcomes and care for patients (Røsstad et al, 2013; NHSE and NHSI, 2020). This is why it is important that stoma patient pathways are standardised for best practice and appropriate skill mix and staffing levels.

Community stoma nurses are essential in providing long-term support for stoma patients (Burch, 2022). However, they also need the support of other healthcare professionals to facilitate a seamless transition from secondary to community and primary care. Community general nurses are instrumental in ensuring that this is achieved in the community, as they provide support for many patients, including those with a stoma. This is why it is important for them to possess basic stoma care skills as part of holistic care. The article describes the patient-specific needs of urostomy patients and the special considerations healthcare professionals must take into account when providing support across community, primary and secondary care settings. With support, guidance and education from stoma nurse specialists, patients and other healthcare professionals can be better prepared for life with a urostomy.

Postoperative recovery at home with a urostomy

After discharged, patients need time to recover and adapt to their new life with a urostomy. As patients begin returning to their daily lives, they often need continuous reinforcement of lifestyle advice, as much of the information provided before surgery is typically forgotten or not retained. Furthermore, patients with newly formed or problematic urostomies often need more supplies. Therefore, regular check-ups with a stoma nurse specialist are recommended for these patients; ideally four to five times within the first 6 months and then annually or more frequently, if necessary (Davenport, 2014; Marinova and Marinova, 2023). This patient-centred approach ensures they receive adequate support and it helps to minimise complications and stoma appliance wastage, as tailored care pathways are essential to meet individual needs and maintain high standards of care. Additionally, regular assessments and personalised care plans are crucial for providing the necessary support and optimising the use of stoma care products.

Urostomy patients frequently encounter issues such as urinary tract infections, skin irritation and leakage, which can significantly affect their quality of life and increase the costs associated with managing these complications. Therefore, frequent evaluations by a stoma specialist nurse are often required. To effectively manage these problems, lifestyle and dietary adjustments may be considered, as well as ensuring that individuals are using well-fitting stoma appliances to reduce the incidence of leaks and related complications, thereby improving patient outcomes.

Many urostomy patients may be discharged within a week of their surgery, and it is likely that they would still have ureteric stents (Figure 2) that help keep the ureters open during healing. While the stents are usually removed around 10–14 days after the operation, they may sometimes be left in longer and fall out on their own (Association of Stoma Care Nurses, 2019; Marinova et al, 2021). The stoma nurse specialist in the hospital teaches the patients how to manage the stents to avoid pulling on them when changing the urostomy bag. Mucus can accumulate and block the stents, so patients are advised to drink 1.5 to 2 litres of fluids daily to help flush out the mucus and prevent build-up. Depending on where the patient lives, they will either be visited by a stoma nurse specialist at home or seen in a community clinic within 10-14 days of discharge. However, other health professionals should also be knowledgeable about stent care and what to do if they fall out prematurely. The general advice is to not reinsert stents if they fall out, to monitor the urostomy function instead and to report any concerns (Marinova et al, 2021).

While many urostomies are created as a result of cancers such as urinary tract, cervical and bowel cancer, they are also performed for various non-cancerous conditions. Depending on the type of disorder, surgical procedures and the need for radiotherapy and other treatments, patients may experience sexual dysfunction, which usually is temporary, but may become permanent in some cases. Sexual dysfunction refers to any problem that prevents an individual or couple from experiencing satisfaction during sexual activity. It is estimated that up to 60% of people with urostomy, colostomy and ileostomy experience some sort of sexual dysfunction (Sutsunbuloglu et al, 2018). It can affect any phase of the sexual response cycle, including desire, arousal, orgasm and resolution. It can occur because of nerve damage during surgery, radiation therapy, advanced diseases, surgical techniques or the surgeon's lack of expertise. Other contributing factors include lack of sexual desire and interest resulting from stoma-related psychological and body image concerns (Sarabi et al, 2017; Sutsunbuloglu et al, 2018). While all urostomy patients may not experience sexual dysfunction, those who undergo operations involving the removal of the rectum, bladder, uterus or prostate are at much higher risk. Common symptoms in both men and women include temporary or permanent impotence, loss of libido, difficulty achieving orgasm and psychological issues, such as increased anxiety and negative body image.

Men may experience erectile dysfunction (difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection) and ejaculatory issues, such as retrograde ejaculation (where sperm enters the bladder instead of the penis, leading to cloudy urine) or an absence of ejaculation. Men may need specialist advice and support to discuss the use of devices and medications to assist with erectile dysfunction and consult a sexual health specialist. It is fundamental to discuss any potential issues with retrograde ejaculation and sperm health before surgery, especially if they are planning to have children and will be undergoing radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Use of sperm banks may be offered to ensure safe collection and storage of sperm.

Women may experience discomfort and pain during intercourse (dyspareunia), vaginal dryness or loss of sensation. They may need specialist advice and support from pelvic floor rehabilitation specialists or a sexual health specialist. Vaginal lubricants may be recommended to help with discomfort. Up to 79% of people with urostomy, ileostomy and colostomy report that the risk of sexual dysfunction following surgery was not discussed with them (Sutsunbuloglu et al, 2018). Community nurses, GPs, surgeons, or stoma nurse specialists should discuss the possibility of sexual dysfunction before and after surgery and make appropriate referrals, if needed. These symptoms are typically temporary and often resolve within a few months or up to a year. In cases of prolonged dysfunction or permanent damage, especially with radical surgeries for advance pelvic organ cancers, the patient may be referred to a specialist urologist, gynaecologist, or psychologist.

It is also important to consider the person's age and to establish the presence of sexual dysfunction before surgery, as the average age of an ostomate is 65 to 70 years (Romao et al, 2020). By 40 years of age, around 40% of men experience some degree of erectile dysfunction. This figure rises to nearly 70% by the age of 70 years. Complete erectile dysfunction affects 5% of men at the age of 40 years, increasing to 15% by the age of 70 years (Echeverri et al, 2016). It is therefore significant to enquire about pre-existing sexual dysfunction to ensure that patients are given realistic expectations when this topic is discussed.

Diet with a urostomy

Urostomy is a life-changing surgery, performed to save or improve patients' lives. The aim is to ensure that these patients return to their lives as it was before surgery. Diet is usually one of the most discussed topics as food is an important part of social and cultural belonging. Urostomy patients usually do not have any particular dietary requirements, however, it is recommended that they carefully and gradually introduce normal diet as part of post-operative recovery. The area from where a segment of small intestine was removed to make a conduit or reservoir may need time to heal (Marinova et al, 2021; Burch, 2022). However, there are some foods known to cause changes to urine odour that urostomy patients and their carers and healthcare professionals need to know about (Table 1). Consuming red fruit, vegetables, such as beetroot, and fruit drinks can turn the urine red. It is important to note that these are not only specific to people who have a urostomy, as anyone's urine odour may be affected by the consumption of these foods. Avoiding these can reduce unnecessary stress for urostomy patients and prevent incorrect diagnosis of urinary tract infections.

| May increase stoma odour | |

|---|---|

| Asparagus | Eggs |

| Fish | Cabbage |

| Onion | Cauliflower |

| Garlic | Sprouts |

| Strong cheese | Broccoli |

Depending on which part of the small intestine was used to create the urinary conduit, such as part ileum removed to form the urostomy, some patients may have an increased risk of vitamin B12 deficiency and may require supplementation. Knowledge of this dietary guidance for urostomy patients is very important for a seamless transition from acute to community care post-discharge from hospitals. Despite receiving education from stoma nurse specialists during pre-operative counselling and post-operative care, many patients often forget or only vaguely recall the information once they are back home (Kessels, 2003). Healthcare professionals should be aware of the patient's specific dietary needs to reinforce dietary guidance as needed.

Hydration with urostomy

Most urostomy-related complications are related to hydration so it is important to ensure that patients adhere to good hydration practices. They may need to drink 20-30% more fluids than the general population to ensure hydration and manage excessive mucus build-up. Mucus build-up is common for urostomy patients, as their urostomy conduit/reservoir is made from the intestine, which naturally produces lubricant or mucus. Mucus may accumulate around the urostomy or be visible inside the urostomy bag. Good hydration and extra vitamin C and cranberry juice are recommended to manage this (Marinova et al, 2021).

The average urostomy urine output is similar to the general population. A healthy person typically produces between 800 and 2000 millilitres of urine each day, assuming they consume around 2 litres of fluids daily. A urostomy produces urine constantly, therefore the patient and healthcare professionals should be taught to monitor for any concerning signs and symptoms. While there are no specific recommendations about hydration with urostomy, cranberry juice is often recommended. Its natural compounds can improve urine odour, particularly benzoic acid and hippuric acid.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common complication for individuals with a urostomy. Since the urinary tract includes a portion of the small intestine in urostomy patients, the risk of infection is higher, though it can be managed. Stenosis of the urostomy can lead to recurrent UTIs. When stenosis occurs, it can cause a narrowing of the stoma and impede urine flow. Cranberry juice is known for its ability to reduce incidents of UTIs and maintain urinary tract health that can also influence the odour. The common recommendation fro urostomy patient is 250 ml of cranberry juice per day to prevent UTIs (Marinova et al, 2021). Good hydration is also important for preventing UTIs. Drinking plenty of fluids, especially water, helps dilute urine and ensures frequent urination, which helps flush bacteria from the urinary tract before the infection begins (Hooton, 2018).

Since the ileal conduit is created from a part of the bowel, it will always be colonised with bacteria, which may almost certainly result in a positive urine sample and inappropriate antibiotic treatment. Therefore, positive urine samples and bacteriuria in urostomy patients should be treated with antibiotics only if symptoms of a UTI are present (Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurse Society [WOCN], 2018; Marinova et al, 2021). When infection is suspected, it is important to take urine samples using the correct procedure to avoid contamination and false positive results. A urine sample should not be taken directly from the urostomy bag (WOCN Society, 2018; Marinova et al, 2021).

Crystal formation can occur if the skin around the stoma is frequently exposed to alkaline urine. These crystals manifest as hard, white or grey lumps on the stoma or the surrounding skin, potentially causing pain and bleeding. In some cases, crystal formation can even lead to leaks from the urostomy bag, exacerbating the issue. To prevent this, it is crucial to protect the peristomal skin and use a well-fitting baseplate. Cleaning the area with a 50/50 solution of white vinegar and water can help reduce crystals, as can maintaining a more acidic pH in the urine by consuming vitamin C and cranberry juice.

Understanding hydration guidance is crucial for urostomy patients to ensure a smooth transition from hospital to home and community, and prevent or reduce the risk of developing common complications. Healthcare professionals involved in ongoing patient care must be knowledgeable about the patient's specific hydration requirements, enabling them to reinforce this guidance as necessary. There is also some evidence that patients with urostomies may be at a higher risk of chronic kidney disease, however, there is no evidence confirming its directly connection to urostomy. Pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes, cardiac issues, hypertension and old age are possible causes (Naganuma et al, 2012).

Medications

Another important element of urostomy patients-centred follow-up pathways is ensuring that these patients have a good understanding of medication management specific to their condition. Although medication does not normally have a significant effect on patients with urostomy, some medicines may change the urine colour. Ibuprofen, a common pain reliever, can sometimes result in red urine. Different antibiotics, such as Rifampin and Metronidazole, may cause a reddish-orange hue and brownish shade respectively. Amitriptyline, an antidepressant, might give urine a blue-green tint. Senna, a laxative, can turn urine yellow-brown and Nitrofurantoin, used for UTIs, can cause a brown colour. These changes are generally harmless and should revert once the medication is discontinued. However, if patients notice any unusual changes in their urine colour, it is always best to consult with a healthcare professional.

Warfarin is a medication commonly used to thin the blood, therefore, patients should not be advised to drink cranberry, grapefruit or pomegranate juice with it. These may increase the effect of Warfarin and may cause complications associated with excessive dosage. Making sure that the patients and healthcare providers are informed about these potential issues is crucial for making well-informed decisions regarding medication management and ensuring effective treatment outcomes.

Routine tests

Unlike other stoma patients, urostomy patients are not normally prone to vitamin and mineral losses, so there are no recommendations for routine tests. Chronic dehydration or UTIs may need to be checked for early detection of any underlying cause. Symptoms of a UTI may include foul-smelling urine, cloudiness, darker colour, or blood in the urine, along with fever and abdominal and back pain. If a UTI is suspected, a urine sample from the urostomy will be needed to confirm the infection and determine the appropriate antibiotic. While this is typically done at the GP's practice, patients, carers and other healthcare professionals may be asked to collect the sample at home.

A urine sample should never be taken from the urine already in the stoma bag, but directly from the urostomy (Marinova et al, 2021). As previously mentioned, a urostomy is created using a segment of the intestine, and urine samples often test positive for intestinal bacteria. Antibiotic treatment is only necessary if the patient is also experiencing symptoms such as fever, chills and back pain.

Urine sample procedure

Collecting enough urine may take up to 15-20 minutes (WOCN Society, 2018; Marinova et al, 2021). Equipment: needed includes cleaning wipes, warm water, paper towels, rubbish bag, a new stoma bag, clean and sterile gloves, a sterile urine collection container, sterile gauze, sterile cleaning solution or sterile normal saline, intermittent catheter (if available), water-soluble lubricant.

If a catheter is unavailable, follow steps 1–8 and then proceed with the following steps to complete the collection:

If the patient has two stomas, such as a urostomy and an ileostomy, colostomy or jejunostomy, it is important to change the urostomy bag first to prevent cross-contamination and reduce the risk of a urinary tract infection. Otherwise, urostomy patients are advised to have the same routine tests, as any other person would, as part of best practice.

Stoma appliances and accessories

Urostomy patients need to use specific urostomy bags that are unique to their needs and cannot be interchanged with other appliances, such as an ileostomy or colostomy bags. This is because they have an anti-reflux valve, preventing the urine from flowing back to the urostomy, which prevents possible infection. Such valves are not available in other stoma bags. Urostomy bags (Figure 3), like other stoma appliances, come in one-piece and two-piece systems, and flat and convex baseplates.

Typically, urostomy patients are advised to use between 10 to 20 urostomy stoma bags per month, depending on how frequently they need to change their bags. It is recommended to change bags every 2 to 3 days. (PrescQIPP CIC, 2015; Marinova et al, 2021). Ostomates may also need to connect their urostomy bag to a night drainage bag to avoid having to wake up to empty their bag during the night or have a leg bag to use if out and about, to avoid having to empty the urostomy bag too often. A night drainage bag may also be used if patients are bedbound or have reduced mobility.

Accessories like stoma paste, seals and flange extenders are generally not routinely prescribed and are reserved for patients with specific complications, such as leaks and skin irritations. The need for these accessories varies based on individual patient requirements and the type of stoma. These accessories are not given unless recommended by a stoma nurse specialist. Accessories and stoma appliances are costly and many areas around the UK are guided by prescription guidelines or formularies. However, it is crucial to understand that no single stoma bag or brand fits all patients. Therefore, recommending a generic brand for everyone is not appropriate. Stoma bags also serve as skin care products and stoma nurse specialists select them based on each patient's unique needs. While formularies and guidelines often suggest quantities of products per month or year, these recommendations are influenced by various factors. Clinicians should recognise that these guidelines may not be suitable for all patients, especially those with complex stoma needs. Additionally, some patients may use fewer bags than recommended, which should be considered to avoid overprescribing. Healthcare professionals must take all these factors into account when making prescribing decisions for urostomy patients.

Patient follow up and important considerations

While follow-up pathways for urostomy patients may differ across regions, they generally follow a similar structure, particularly focusing on the first 3 months after surgery when patients are adjusting to their new stoma. During this period, more frequent follow-ups are provided. Based on structured follow-up experiences, patients benefit from intensified follow-ups in the first 30 days after surgery, with clinical reviews every 10-14 days or more frequently if complications arise. The frequency of follow-ups then decreases, with reviews at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months, eventually transitioning to annual follow-ups (Taneja et al, 2017; Marinova and Marinova, 2023; Mthombeni et al, 2023). The frequency of follow-ups is influenced by how well patients are adjusting to their urostomy, whether they encounter any complications, or if they wish to explore different procedures or appliances.

Urostomy patients need life-long support throughout their journey with a stoma. It is crucial that stoma care services are easily accessible to provide this support and that other healthcare professionals are trained to assist in various healthcare settings. This requires investment in the specialist nurses' workforce and infrastructure, as well as patient-centred pathways tailored to the type of stoma to ensure consistent care regardless of the patient's location.

Structured pathways are essential as they allow healthcare professionals and patients to focus on their specific needs tailored for their stoma types and provide recommendations for specific patient groups. Urostomy patients will need special consideration about ureteric stents management, prevention of UTIs and management of mucus. Their needs will also vary depending on the season, as more issues may arise in hot weather. Having an adequate number of stoma specialist nurses is essential for delivering optimal care to urostomy patients. These nurses play a vital role in reducing healthcare costs, alleviating pressure on emergency departments and easing the burden on general practitioners and consultant clinics by independently managing urostomy patients through nurse-led services. All of this must be considered when planning the workforce and workload, and setting care standards for urostomy patients. This requirement should be thoughtfully incorporated into national pathways and annual workforce planning to ensure these patients receive adequate support.

Conclusions

Creating well-defined and structured pathways to assist urostomy patients and healthcare professionals through the perioperative journey of a stoma-forming surgery is essential for delivering high-quality patient care and achieving positive outcomes. These pathways should be customised to meet the specific needs of different patients and types of stomas, fostering a more patient-centred approach and improving patient outcomes. To accomplish this, stoma care services must be adequately resourced to provide continuous support throughout an the journey of a person with a stoma.. This includes offering procedures such as ureteric stent care, urostomy urine samples and UTI management services to all urostomy patients, although these are currently limited because of workforce shortages. Additionally, healthcare professionals across all settings—primary, secondary, and community—should be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to care for these patients effectively, thereby reducing complications and hospital admissions. Investing in these areas will create a supportive and efficient healthcare environment that enhances the quality of life for urostomy patients and promotes positive health outcomes. Investing in independent nursing healthcare providers is an avenue to be explored, as this has already proven to be more effective and efficient in areas such as dermatology and orthopaedics.