A district nurse is a qualified nurse who has completed a post-registration qualification in the specialist field of district nursing, recognised by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2024). The district nurse role and title were given to nurses who cared for patients at home in a related district or area. The establishment of district nursing in England during the Victorian times was significant as it advanced women's roles and their professions.

Amid debate about social class and working women, the Queen's Nursing Institute (QNI) began offering professional training to district nurses in 1887 (QNI, 2024a). The QNI defines district nurses as senior nurses who manage community care within the UK's National Health Service (QNI, 2024b). While district nurses are also associated with community nursing under an umbrella term, community nursing itself is associated with many different job titles. This can be confusing to the people in need of health care, who may not understand the specialist expertise being delivered to them by qualified district nurses (QNI, 2019a). The NMC standards of proficiency for community nursing specialist practice qualifications acknowledge this variance of community nursing roles and the ever-changing context of community nursing. Further specialist qualifications may be needed to address this (NMC, 2022).

Community district nursing teams have a diverse mix of skills, balancing nursing skills and responsibilities among staff with various qualifications in the district nursing services. The ratio of qualified district nurses to other team members has raised concerns, particularly as the number of commissioned places for the district nurse qualification has been reduced (QNI, 2023). Furthermore, the number of qualified district nurses dropped by 42% between 2010 and 2018, in favour of more skills with less qualified staff. This is in addition to a total decline of nurses working in the NHS community health services by 14%, compared to the number of acute nurses increasing by 9% (King's Fund, 2019).

Data collated by QNI (2023) for the 2021–2022 academic year indicated that 668 district nurses qualified with a specialist practice qualification, a 6% decrease from the previous year. The lack of clarity around the future of the district nurse specialist qualification has made it difficult for nurses in this field to plan their career progression, leading to a staff retention risk (QNI, 2024c).

As community nursing areas expand, leading to the emergence of many different titles, the role of the district nurse increasingly blends into a model of integrated social and hospital care. This approach aims to provide personalised care, often referred to as integrated care (NHS England, 2023). While this is theoretically a good measure to reduce bureaucracy, it could be argued that the specialist district nurse role is considered less favourable than before. District nurses take pride in their role as the key providers of care, often stating that they ‘hold everything together’ (Oxtoby, 2019). They play a crucial part in saving the NHS hundreds of thousands of pounds by enabling patients to remain in their own homes and improving patient outcomes through continuity of care (Oxtoby, 2019; Ford, 2021). With the decline in the number of district nurses, the profession feels that its value in these areas is increasingly under-acknowledged (Oxtoby, 2019).

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu explored the concept of habitus, a complex notion that conceptualises the combination of subjective, objective and social influences on an individual in shaping their perceptions and values. Habitus can relate to how an individual's childhood and parental influences have shaped their personality, progression through life and ability to succeed (Bourdieu, 1992). It relates to the inner workings and minutiae of how something ‘just is’ and has come to be over time.

Habitus can also be applied to a group of individuals that share the same socialisation and therefore, has been referred to as the ‘field’(Bordeieu, 1992). A field is an identified social space that has clearly defined common characteristics, such as an institutional setting or a relationship. An embodiment of how a group has evolved, its relationship to other fields, their perceptions and how it perceives itself are manifested in common characteristics, such as ways of thinking, being and doing things in an agreed way.

Much as an individual develops in personality, honing preferences and adapting to their social influences and boundaries, so it is with a field. Here, habitus applies to the common characteristics of that field rather than the individual person or personality. Studying a specific field provides a foundation for ethnographic analysis, revealing that even individuals within that field may be unaware of the subtle struggles for position and power taking place. Using Bourdieu's theory of habitus and field is a way of exploring and revealing hidden elements to understand the complexities of the field of district nursing.

According to Bourdieu, a field can be viewed as a game in which players compete for capital and power (Bourdieu, 1996). Capital is often represented by economic capital, where power is derived from accumulating financial wealth. Bourdieu noted that there are other forms of capital, most notably social and cultural capital. Therefore, social capital is the ability for a field to build upon its social status in society. All types of capital are under the umbrella of symbolic capital that manifests into key markers and ‘return for investment’. For example, the symbolic capital of research is thought to be knowledge, which can manifest itself in grants (Grenfell and James, 2010).

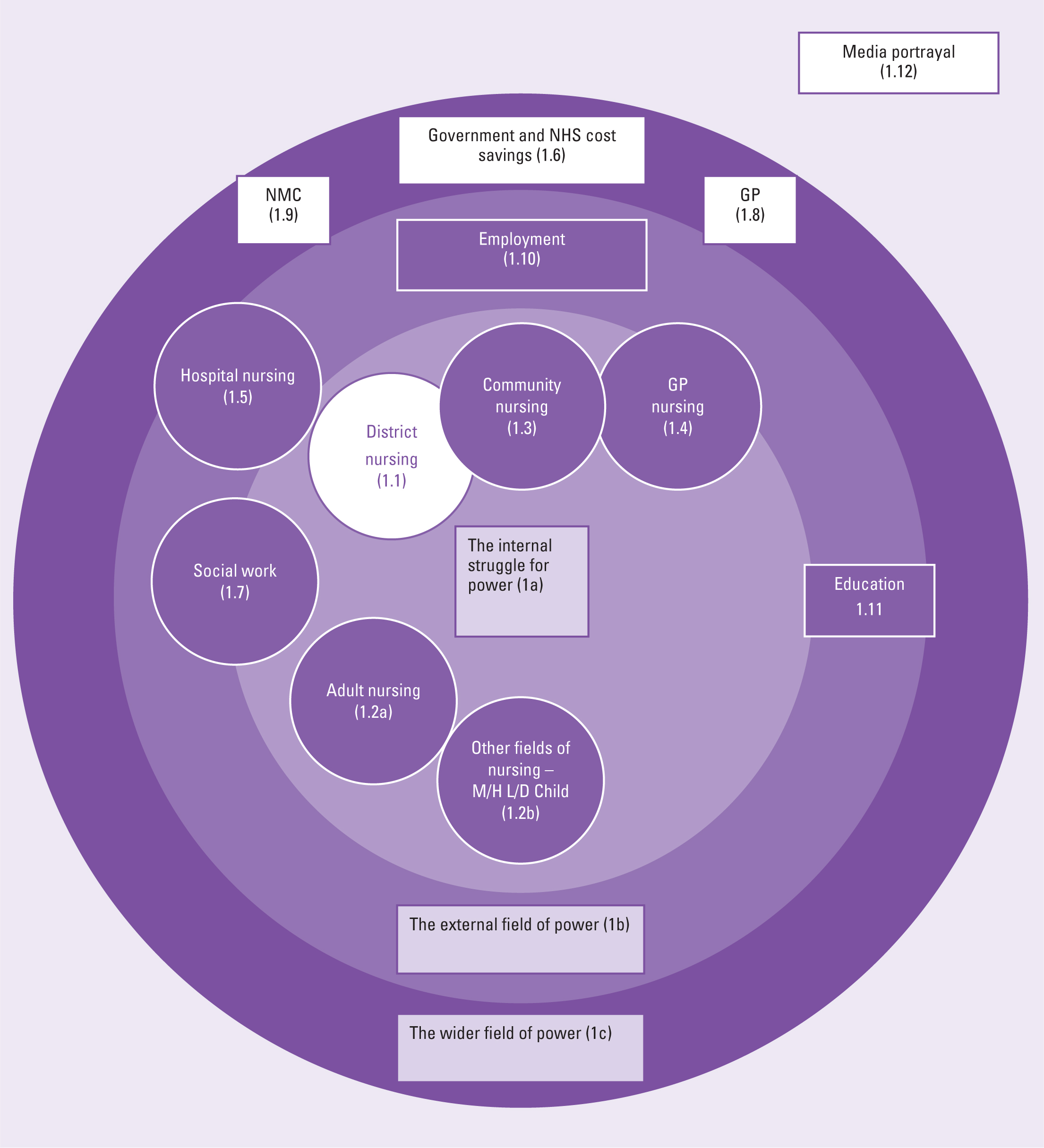

In this article, the author will explore how the symbolic capital of district nursing is rooted in autonomy and responsibility, while also highlighting the complexities of its manifestation because of various external factors. Capital is both the product and the process or ‘game plan’ of the field (Grenfell and James, 2010). Playing for capital is a natural, comfortable and automatic process in the field (Thomson, 2005). District nursing is currently playing for symbolic capital, most notably in defending its specialist qualification, which is central to its autonomy and recognition as a profession. A manifestation of symbolic capital would be an increase in the number of educational placements for district nurse qualifications, along with greater recognition in pre-registration nursing and improved employability in community settings. To understand this, there is a need to identify district nursing's relationship to other fields, the historical beginnings of the profession and how this has changed over time. Figure 1 represents the author's interpretation of the district nursing and its relationship with other fields using Bourdieu's (1996) work.

Understanding the field of district nursing

District nursing as a field (Figure 1.1) is bound by its relationship to other professional fields as well as the four main nursing fields or branches of nurse education: adult nursing (Figure 1.2a), learning disability nursing, child nursing and mental health nursing (Figure 1.2b). Connections to the field of adult nursing are stronger because of clinical placement alignment in pre-registration education; adult pre-registration students, as opposed to those in child, learning disability or mental health nursing, are primarily aligned with district nurse placements. The district nurse has close relationships with other fields in the domain of power, including community nursing—an umbrella term for all community areas (Figure 1.3)—and general practice nurses (Figure 1.4), all of which share the commonality of providing care outside of hospital settings.

While there are many specialist community areas, such as specialist community public health nurses, health visitors and school nurses, not all of these roles are specifically named. The relationships with these community fields pose a threat to district nursing in terms of symbolic capital, as increasing heteronomy is imposed by the politics of the wider field of power (Figure 1c), undermining the value of the district nurse qualification.

Heteronomy is the decrease in autonomy of a field as a result of it being subjected to external influences. This can be seen in the changing definition of its role over historical contexts, with the control of the field becoming heavily dependent on factors such as funding, cost-effectiveness and perceived value. It is evidenced by the significant historical move in the 1990s, when a review of skill mix led to the replacement of district nursing with community nurse teams (NHS Management Executive (NHSME), 1992).

The introduction of digital technology advancements to reduce hospital admissions (Department of Health, 2013) could undermine the role of district nurses, particularly as they have to overcome the challenges of using technology and recognise how this can affect person-centred care. For example, the district nurse's focus may shift from managing the healthcare needs of people and effective communication to inputting data into complex devices (Williams, 2022). The fields of district nursing and community nursing are prime examples of heteronomy, as the boundaries become more permeable (Bathmaker, 2015). Figure 1 explains the relationship of district nurses to other fields and the internal struggle of power. There is an overlapping of fields where community nursing (Figure 1.3) is encroaching on district nursing (Figure 1.1). The district nurse used to have higher pay grades, with considerable responsibility associated with these grades. Lack of education in this field (QNI, 2023) means community nurses, without the specialist practitioner qualification, have been able to apply for the higher grades or bands and district nurse team leader posts (QNI, 2024c).

According to Bathmaker (2015), a field requires boundedness, predictability and a steadfast insularity to be ahead in the social game. District nursing appears to be losing the game on these fronts (Bourdieu 1996), as manifested by the unrecognised capital, the ‘hiddenness’ and its unrecognised value (Grenfell and James, 2010). As a result, the district nurse specialist profession may gradually erode; the only way to stay in the game is to play the capital of being under the umbrella of ‘community nursing’ (Figure 1.3) (Bourdieu, 1996).

However, even the field of community nursing services is poorly understood because it lacks the high national profile, influence and leadership possessed by other fields in the NHS (King's Fund, 2019). In a positive move, a national deputy director for community nursing was appointed for Health Education England, now known as NHS England (Gilroy, 2020).

Challenges in defining profession

Defining the term ‘profession’ can be complex at times. While profession has been defined simply as an occupation (Hugman, 1991), the term is historically identified with having undergone special training to gain possession of an intellectual technique (Carr-Sanders and Wilson, 1962). This is characterised by the acquisition of knowledge over skilled labour, explained by trait theory (Carr-Sanders and Wilson, 1962). In addition, definitions of the term profession suggest that district nursing, at its inception, was a collegiate profession defined as highly autonomous lone workers. Lack of clarity around the term profession has led some to use Bourdieu's interpretation of field to represent it as a profession; one that is defined by what it does rather than what it is (McKnight, 2022).

Before the establishment of the NHS in 1948, 90 years post establishment of the role, the district nurse belonged to the District Nurse Association. According to the 1911 Insurance Act, the association ensured that salaries were paid for by a provident scheme that people paid into (Cohen, 2010). District nurses were seen as so valuable that special houses were built for them after World War 1 in 1930 (QNI, 2022). Visually characterised by a nurse on a bicycle, this image signifies symbolic capital for those in the profession, representing freedom from institutional constraints, routine and skilled labour. A profession where power lies in its own invention, its boundaries and autonomy.

In addition to autonomy, the significance, superiority and importance of the profession also play a role in the field of district nursing (Bourdieu, 1996). Initially trained by the QNI, which was funded by Queen Victoria and recognised as ‘her nurses’ (Cohen, 2010), this historical foundation established district nursing as a distinct profession, defining it as separate from institutional nursing. Furthermore, there was a reported class divide between hospital and community care, where the early 20th century hospitals mainly cared for the poor, while the wealthy were cared for at home (Kirk and Glendinning, 1998).

District nurses have also been referenced as ‘largely upper-class ladies’ (History of District Nursing, 2010). Today, the recognition of the specialist qualifications of district nurses has brought higher pay grades, greater responsibility and the need for autonomous, independent work. However, district nursing remains largely ‘hidden’ from public view, media attention and educational focus—especially when compared to the visibility of acute hospital nursing (Figure 1.5).

Located in the external field of power, and closely touching upon district nurses' struggle for power as a rival in the game rather than a team partner (Bourdieu, 1996), are tensions with acute hospital nursing (Figure 1.5). These tensions can be explained by an apparent lack of understanding, respect and acceptance of each other's varied roles. District nurses have often found themselves tasked with addressing poor patient discharges, while also being aware of myths perpetuated by hospital staff, community staff and university lecturers suggesting that working in the community leads to being deskilled (White, 2019).

The actual reality of the meaning of professional status does not appear to be interpreted into any professional or social capital. District nursing is not generally recognised as a profession comparative to medicine or law, which are other examples of collegiate professions, and furthermore does not lose any other connection to its roots of general nursing. Bourdieu (1999) described this as a habitus divided against itself, where it is ‘doomed to duplication and a double perception of self’.

District nursing appears socially unable to claim full professional capital for four identified reasons. First, the term profession within the public domain is often dissolved purely into occupation, everyday speech and nature of work, such as the ‘caring profession’. Second, building upon the term ‘caring profession’, there is a historical divide between ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about’ those served by the profession (Hugman, 1991). If there is any distinction between a profession that ‘cares for’ rather than just ‘cares about,’ it is traditionally viewed as women's work.

As a result, symbolic capital tends to be awarded to more traditional male professions, such as law and medicine. ‘Caring for’ professions have come to be regarded as only semi-professional (Hugman, 1991). Third, media portrayals of district nursing often depict it as hidden away in patients' homes rather than in institutional settings. This contributes to myths, such as the perception that the field is a place to go to retire (White, 2019) and fosters false impressions that district nurses are uncaring because of their protective measures (ITV News, 2020). Fourth, the dual nature of district nursing, being both specialist and generalist, creates a contradiction that complicates its recognition and attainment as a profession. However, GPs as a profession are also specialist generalist and do not appear to have these same professional capital issues.

Having established the historical context of district nursing as a profession, it appears that this baseline of credibility, along with any social or professional capital acquired, has been gradually ceded to or appropriated by other fields over time (Figure 1.2). The NMC standards (2022), which refer only to community nursing without specifically mentioning district nursing, suggest that the profession has struggled to define and maintain its professional capital in the face of encroaching fields (Bourdieu, 1996) (Figure 2). This underscores what Bourdieu described as the subjective gendered tensions that reveal the fundamental structures and contradictions of the social world (Bourdieu, 1999).

Habitus of district nursing and political changes

Many of the moveable boundaries between curing, caring, social and professional capital are influenced by government agendas, cost efficiency and education requirements in the wider field of power (Figure 1.5). These include the introduction of skill mix and caseload changes (NHS and Community Care Act, 1990) with a move to social care (Figure 1.7).

Significant political changes have been responsible for the eroding of the district nurse profession and autonomy in the Bourdieu (1996) game of field, and thus the loss of symbolic capital to other field players. One of the most significant changes following World War 2 was the shift away from the Victorian model of a superior profession and the authority of the QNI. The Beveridge Report (Beveridge, 1942) laid the groundwork for the establishment of the NHS. For district nursing, this NHS reform meant that they then became employees of local authorities.

In 1968, the QNI ceased the training of district nursing when it was nationalised, marking a complete break from its Victorian heritage and transitioning from its primary habitus to a secondary habitus (Bourdieu, 1992). The difference is that district nursing in its primary habitus pre-employment can defend against change, while in its secondary habitus, once employed, it became subject to external influences. This shift rendered its professional status, education, autonomy and independence open to questioning and made them ‘fair game’ for discussion outside the field (Bourdieu, 1996).

A further key external influence on the district nursing service was the Community Care Act (NHS, 1990). This led to a significant shift in the way care was organised and managed. With the onset of an internal market for providing and purchasing services, the Secretary of State gained power over NHS Trusts, granting them responsibilities for business agreements, including borrowing money, generating income and raising revenue from services. For district nurses, this marked the beginning of a shift in workload, as personal care tasks such as washing and dressing—previously considered nursing responsibilities—were increasingly recognised as social needs.

Consequently, their caseloads could be re-evaluated, with such care becoming the responsibility of local authorities. Furthermore, a reduction in hospital beds, a decline of one-quarter between 1982 and 1992 (Wistow, 1995) and hospital closures meant more complex care began to be delivered in the community (Marks, 1991). This recognition could mean a shift towards a more curative role and a potential return to a collegiate profession.

However, another development from the Community Care Act (NHS and Community Care Act, 1990) was the introduction of GP fundholding, which allowed GPs to manage their own practice and budget, leading to a different impact on the profession.

Relationship to fields of GPs and GP practice nurses

GP fundholding was considered either a welcome reform or a contentious issue, raising doubts over the possible conflict between purchasing and providing services (Hiscock and Pearson, 1996). Community nurses felt that their service provision was threatened by competition from employed nurses, particularly general practice nurses (Figure 1.4). Conversely, in some areas, community nurses felt that GPs exerted ownership over them and imposed unreasonable demands that diminished their autonomy (Hiscock and Pearson, 1996).

Ultimately, the shift in power lay with the GPs, positioning them within a broader field of power (Figure 1.8). Defining the roles of the district nurse and practice nurse was crucial to playing the game of capital as defined by Bourdieu (1996). GPs had taken some of the professional capital from district nurses by undermining autonomy by working to define boundaries with general practice nursing depending on role speciality. District nurses were able to stay in the game by playing to the strengths of their professional capital in the field (Bourdieu, 1996).

A comment from a qualitative study reflects this well: ‘If you feel that you are two in a practice, then yes you will be isolated. If you think of yourself as a community nurse, there are fifteen of them in the practice and you are not isolated any more’ (Hiscock and Pearson, 1996). This highlights another aspect of Bourdieu's concept of field, where district nurses seek to contest for symbolic capital in the community field, ultimately benefiting their professional standing (Figure 1).

Overall, the policy seems to initiate a shift in care priorities, emphasising cost savings and value for money, rather than solely focusing on the quality and safety of person-centred care at the point of need. This was underscored in a study about the skill mix, aptly titled, ‘Value for money’ (NHSME, 1992). The report, based on research into two community sites, aimed to ‘get the very best from the skills that nurses possess'.

While it advocated for a cost-effective service that was deemed ‘grossly wasteful’ regarding the use of highly qualified nursing resources, it still prioritised maintaining high quality for both patients and purchasers. For district nurses, this meant that greater delegation of care was necessary to less qualified staff nurses or even healthcare assistants in teams. This shift could potentially lower the standard of care, as district nurses typically employ a wide range of skills during home visits, rather than focusing on a single, allocated task (McIntosh, 2000).

More recently, skill mix has become a concern, as the increasing complexity of work required does not align with the demands placed on the service (QNI, 2022). Other surveys show that more nursing associates-a trained role designed to bridge the gap between healthcare assistants and registered nurses (Health Education England, 2020)-are identified within district nursing teams than previously recorded (QNI, 2024c). However, in 1992, this marked the beginning of a decline in post-registration specialist qualifications.

District nurses maintained their professional capital by taking on team leader roles and managing a team of qualified community staff nurses and healthcare assistants. Unfortunately, this arrangement reportedly left the qualified staff nurses feeling dissatisfied with their roles (Hallett and Pateman, 2000). This could be significant to myths portrayed by White (2019) and affect the employability of students in community nursing (Figure 1.10).

While district nurses continue to provide services to GPs, they are not employed by GP practices, unlike GP nurses. Instead, they operate under contractual agreements established by Integrated Care Services, which include a variety of NHS organisations. Some community services are delivered by larger acute trusts. As a service provision, they move to a mediated profession (Johnson, 1972) and more in the domain of other nursing services. However, the qualified district nurse has maintained closure by still being regarded as a specialist.

The shift in skill mix continues to reinforce the district nurse's identity as a specialist who can delegate various ‘caring for’ roles needed by patients. The specialist qualification, despite debates about its purpose, helps to socially define the role as a career progression and an exclusive status reward. The concept of closure helps define professional status for career progression and prestige (Hugman, 1991); this would only be recognised by those belonging to the profession itself.

Conflict between specialist and generalist roles

There is a specialist and generalist conflict in the field of district nursing. District nurses are specialists in their field: managing complex long-term conditions, keeping patients at home, being independent and working alone. Yet the work can also be very generalist, requiring a broad knowledge base across various areas of care.

The role requirements of a district nurse can encompass a wide range of patient needs, including making referrals and implementing basic skills from other professionals, such as dietitians and occupational therapists. For example, they may provide basic dietary advice and arrange for equipment like commodes and chair raisers. Caseloads are also evolving and consist of patients that require even more acute and complex care to keep them at home (QNI, 2019a).

Nonetheless when visiting patients at home, the district nurse uses expertise in patient care that can be termed as ‘invisible’ skills such as risk assessment, judgement and decision making (McIntosh, 2000), ensuring that the patient is safe in their own home and does not need continuous supervision. This echoes the historical role of district nurses, who also adapted to meet a wide range of needs beyond traditional adult nursing. A district nurse may often find that a patient prioritises a visit to the hairdresser over professional advice or wound care. Again, this may be perceived as indicative of low social status or capital, where the value of the nursing service can be overlooked. Historical accounts (QNI, 2024a) highlight how district nurses often had to improvise as a result of a lack of equipment, demonstrating resourcefulness and a sense of heroism in managing situations with whatever was available.

However, they also recount instances where a district nurse was advised not to visit patients while Coronation Street was on, reflecting the challenges they faced in balancing their professional responsibilities with societal perceptions. (QNI, 2024a). Similar to the distinction between ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about,’ Hugman (1991) notes that the difference between caring roles and curing roles helps define a profession.

Curing roles are viewed as professional positions associated with acquired knowledge, education and privilege, whereas caring roles are often seen as ancillary positions linked to working-class and manual labour. Despite possessing specialist knowledge, the district nurse cannot detach from the caring role necessary to provide the quality of care required. Keeping patients out of hospital has lent itself to curing and caring, or even ‘prevention rather than cure’. From a professional status, literature similarly notes this anomaly, suggesting that roles in healthcare are often viewed as either educated and specialised or caring and generalist. This creates a perception that these categories are binary opposites, implying that a profession cannot embody both attributes simultaneously (Meerabeau, 2004).

There are numerous anomalies regarding what is deemed professional or prestigious in healthcare. For instance, technical skills are often regarded as knowledge-based, leading students on clinical placements to feel that they are not truly learning unless they are actively engaged in developing these skills. This emphasis on technical proficiency can overshadow other essential aspects of care, such as communication and empathy (Reynolds, 2022). This perspective also extends to specific fields of nursing, such as elderly care, which can be perceived as having low status when focused on maintaining a patient's daily activities. This perception only changes when acute or emergency issues arise, at which point the social prestige of the role is elevated. This dichotomy underscores a bias that undervalues the critical, ongoing support provided in elder care settings (Hugman, 1991).

The role of caring or skilled labour in preventing hospital admissions should not be underestimated. Knowledge and expertise are crucial for delivering effective health promotion and fostering an environment where patients can make informed choices, while also allowing for a form of indirect influence. The power dynamic between a district nurse and patient differs to that of a hospital nurse and patient (Hugman, 1991). For example, the acute nature of the care provided in the hospital means that the patient can rely on the nurse to do things for them.

In the community, patients are more independent and the nurse visits their home as a guest. In this dynamic, the power lies with the patient, necessitating that the nurse use their interpersonal skills to facilitate greater choice while subtly maintaining an indirect influence. This perspective is intriguing when examining power through the lens of symbolic capital. While one might assume that having power over a patient holds significant value, the lack of direct control actually highlights the need for greater expertise in communication skills and partnership working. This dynamic suggests a more collaborative, collegiate approach within the nursing profession.

When considering the skills and expertise involved in care giving, there is a professional degree of intimacy required to recognise the individuality of the person receiving the service (Philip, 1979). This emphasis on personal connection, rather than merely focusing on the task at hand, exemplifies what can be described as an ‘invisible skill’ (McIntosh, 2000). Since the establishment of district nursing, the role has increasingly encompassed general caring tasks, such as washing and dressing. Today, many of these activities might be classified as social care if there is no underlying nursing need, such as in palliative care. The balance between caring and curing, as well as between social and professional capital, has always been fluid and subject to change.

Historical educational moves and the impact on district nursing

Project 2000 in the 1990s was the biggest change in nursing, with the move from hospital-based to university-based nursing. Changes, such as the introduction of the four nursing branches (Longley et al, 2007), were introduced to strengthen the overall credibility of nursing as a profession and facilitate higher entry-level qualifications. The move to university education meant the ability to expand and develop student placements in the community setting. This shift transformed previous purely observational or short ‘experience’ or ‘taster’ visits into opportunities for longer, assessed placements, providing students with more comprehensive hands-on experience.

For nursing overall, alongside becoming a degree-only profession by 2015 (Ford, 2008), the move to university meant a higher status of qualification and professional status. While this transition allowed individuals to gain professional capital, it remains unclear whether nursing as a whole benefited in the same way. Conflicts between vocational and professional roles have complicated the accumulation of social and economic capital, leading to ambiguity regarding the overall advancement of the profession (Bourdieu, 1992; Hayes, 2012).

For individual district nurses, longer assessed student placements meant increased workload rather than an opportunity to gain professional capital in the form of a raised profile among students (Kenyon and Peckover, 2008; Brooks and Rojahn, 2011). For community nursing, indicators suggesting the need for its own distinct field or branch have been highlighted in commissioned reports (Longley et al, 2007; Willis, 2015), but these recommendations have not been implemented. The fact that this issue has been highlighted for over 17 years without any official action suggests a lack of priority in developing this area of education. This lack of action is particularly concerning given the recent NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2023), which emphasises the need to employ more nurses in the community, especially in light of the sharp decline in the workforce (QNI, 2019b; Senek et al, 2023). Workforce plans aim for a 41% increase in district nurse training places by 2028–2029 and a further 150% increase by 2031–2032 (NHSE, 2023).

In 2018, the NMC outlined new proficiencies for nursing including extensive nursing procedures or skills (NMC, 2018). However, students often find it challenging to meet these requirements in community settings, particularly for tasks such as administering intravenous medication, performing blood gas analyses, conducting blood transfusions and carrying out electrocardiogram investigations.

The practice of these skills is crucial for students, which can lead to a perception that community-focused skills are less important in comparison. This dynamic may inadvertently strengthen an acute-focused adult nursing workforce at the expense of developing competencies in community settings. In terms of Bourdieu's (1996) habitus and field, even when district nursing aligns with community or plays the community field, it still appears to lose symbolic capital.

Media portrayal and district nursing

Bourdieu's concept of cultural capital underscores the social function of television as a contributing factor in portraying the excitement of emergency situations, which can attract social capital to nursing (Bourdieu, 1992). Historically, nursing has been viewed as a ‘doctor's handmaiden’ (Meerabeau, 2004; Nyborg and Hvalvik, 2022).

However, contemporary television dramas have elevated the status of nurses to that of lifesavers, contrasting sharply with the previously lower status associated with caring roles, which encompassed moral, spiritual or practical aspects (Hayes, 2012). This shift mirrors the care/cure dichotomy, emphasising the dynamic nature of nursing's perceived value in society.

Owing to this, TV programmes sell the idea that the hospital nurse defines the profession of nursing because it demonstrates a ‘virtuoso’ role. Virtuoso roles can be defined as the epitome of a profession (Hugman, 1991). They radiate an aura of authority by having ‘glamour’ (Nokes, 1967; Davies, 1985) and this is represented visually by knowledge and experience, effective autonomy and a degree of distance from the ‘dirty work’ that would be carried out by ancillary staff.

These roles are seen as curing, rather than caring, and represent the move to a higher social status and therefore, ‘profession’. District nurses could once be seen embodying a virtuoso role, characterised by their extensive knowledge, experience and effective autonomy in delivering care. Particularly during World War 2, they were celebrated for their heroism and recorded bravery. One such example is continuing their duties after extinguishing bomb fires at a patient's house (Cohen, 2010). Current media portrayals tend to favour documentaries to showcase a district nurse's work rather than dramatic representations, which are often seen as more compelling. For instance, Lavery and Henshall (2022) collected questionnaire data from first-year student nurses regarding media portrayals of community nursing. The results revealed that the most frequently cited sources were hospital dramas, including 24 Hours in A&E, Casualty and Holby City.

Conclusions

This article explored various elements that impact the professional status of district nursing as a distinct field. It examined the internal struggles for power in the nursing profession, the external challenges related to education and employment and the broader influences, such as government agendas, that threaten both the role and the quality of services provided by district nurses. Reviewing the history of district nursing may reveal the significance of professional status and therefore, the symbolic capital of the field and how political changes have affected this. It could be argued that the historical term ‘district nurse’ holds less social, professional and symbolic capital today than it did at the time of its inception. However, plans do appear to recognise the impact that the district nurse qualification has on safety.

The discussion suggests that, to remain relevant in the field of community nursing as defined by Bourdieu, district nursing must leverage its strengths in response to political changes and developments from the NMC. District nursing should advocate for its symbolic capital, emphasising autonomy as a key strength. For example, community nursing needs to focus on curricula so that students have more exposure to community nurse placements, community nurse theory and simulation.

NMC proficiencies could be reviewed to elevate the profile of community nursing and ensure that there is more focus on specialist community nursing skills, such as autonomous thinking, lone working and adaptability, rather than the technical clinical skills that students feel pressurised to complete whether specialising in an area that practises those skills regularly or not.

Where it is not possible for students to achieve proficiencies in lone working and autonomous thinking in community practice, technologies such as simulation and virtual reality could be used to fill the gap. The NMC could also consider and recognise community nursing as a nursing education branch of its own alongside current nursing branches of mental health, children and young people, and learning disabilities, as suggested in reports since 2007.

Key points

- District nursing's professional and symbolic capital has declined overtime because of external influences

- Examining the habitus and field of district nursing demonstrates an under-investment in district nurse education and the reason behind it

- There is a need to elevate the profile of district and community nursing in education and ensure that pre-registration students are adequately prepared to work directly in community settings upon graduation

CPD reflective questions

- Reflect on the relationship between acute and community adult nursing. Is there a mutual respect? How can this be strengthened?

- How can district nursing raise its profile in pre-registration nursing programmes?

- Would establishing a nationally recognised community adult nursing branch help raise its profile?